Civil War Medicine

Ina Dixon

During the Civil War, both sides were devastated by battle and disease. Nurses, surgeons, and physicians rose to the challenge of healing a nation and advanced medicine into the modern age.

From the stench of putrefying flesh wafting through unsanitary and crowded camps to the unglamorous illnesses of syphilis and dysentery, our modern disgust toward Civil War medical practices is generally justified.

However, while “advanced” or “hygienic” may not be terms attributed to medicine in the nineteenth century, modern hospital practices and treatment methods owe much to the legacy of Civil War medicine. Of the approximately 620,000 soldiers who died in the war, two-thirds of these deaths were not the result of enemy fire, but of a force stronger than any army of men: disease. Combating disease as well treating the legions of wounded soldiers pushed Americans to rethink their theories on health and develop efficient practices to care for the sick and wounded.

At the beginning of the Civil War, medical equipment and knowledge was hardly up to the challenges posed by the wounds, infections and diseases which plagued millions on both sides. Illnesses like dysentery, typhoid fever, pneumonia, mumps, measles and tuberculosis spread among the poorly sanitized camps, felling men already weakened by fierce fighting and meager diet. Additionally, armies initially struggled to efficiently tend to and transport their wounded, inadvertently sacrificing more lives to mere disorganization.

For medical practitioners in the field during the Civil War, germ theory, antiseptic (clean) medical practices, advanced equipment, and organized hospitalization systems were virtually unknown. Medical training was just emerging out of the “heroic era,” a time where physicians advocated bloodletting, purging, blistering (or a combination of all three) to rebalance the humors of the body and remedy the sick. Physicians were also often encouraged to treat diseases like syphilis with mercury, a toxic treatment, to say the least. These aggressive “remedies” of the heroic era of medicine were often worse than patients’ diseases; those who overcame illness during the war owed their recoveries less to the ingenuity of contemporary medicine than to grit and chance. Luck was a rarity in camps where poor sanitation, bad hygiene and diet bred disease, infection, and death.

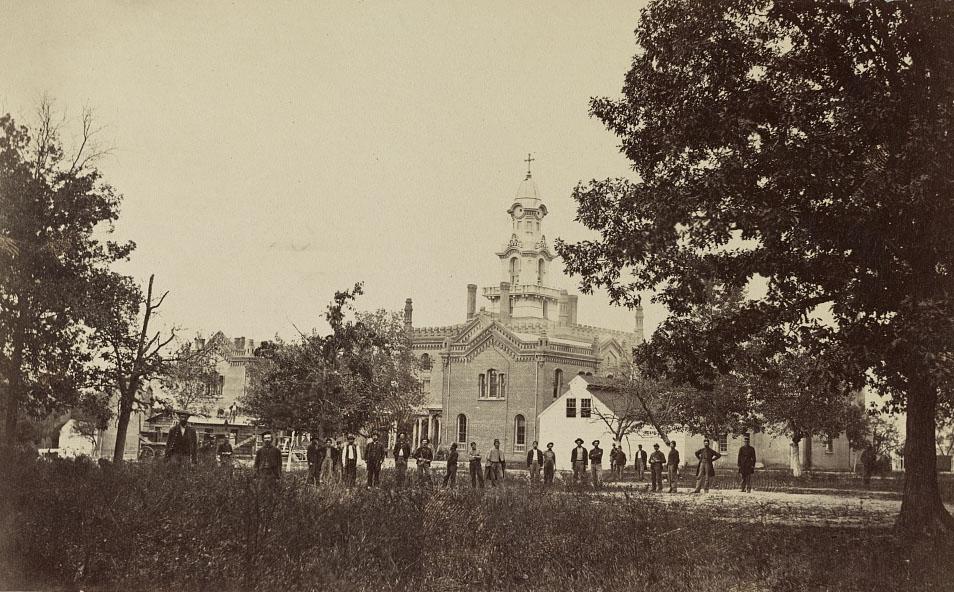

The wounded and sick suffered from the haphazard hospitalization systems that existed at the start of the Civil War. As battles ended, the wounded were rushed down railroad lines to nearby cities and towns, where doctors and nurses coped with the onslaught of dying men in makeshift hospitals. These hospitals saw a great influx of wounded from both sides and the wounded and dying filled the available facilities to the brim. The Fairfax Seminary, for example, opened its doors twenty years prior to the war with only fourteen students, but it housed an overwhelming 1,700 sick and wounded soldiers during the course of the war.

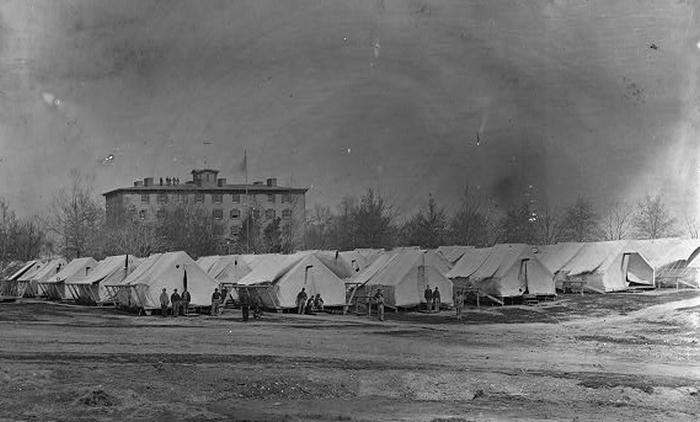

On his many tours of these improvised hospitals, the great American poet and Civil War nurse Walt Whitman noted in his Memoranda during the War the disorderly death and waste of early Civil War medicine. At the camp hospital of the Army of the Potomac in Falmouth, Virginia in 1862, Whitman saw “a heap of amputated feet, legs, arms, hands, &c, a full load for a one-horse cart” and “several dead bodies” lying near. Of the “hospital” itself, which was a brick mansion before the battle of Fredericksburg changed its use, Whitman observed that it was “quite crowded, upstairs and down, everything impromptu, no system, all bad enough, but I have no doubt the best that can be done; all the wounds pretty bad, some frightful, the men in their old clothes, unclean and bloody.” Of the division hospitals, Whitman noted that these were “merely tents, and sometimes very poor ones, the wounded lying on the ground, lucky if their blankets are spread on layers of pine or hemlock twigs or small leaves.”

However, the heavy and constant demands of the sick and wounded sped up the technological progression of medicine, wrenching American medical practices into the light of modernity. Field and pavilion hospitals replaced makeshift ones and efficient hospitalization systems encouraged the accumulation of medical records and reports, which slowed bad practices as accessible knowledge spread the use of beneficial treatments.

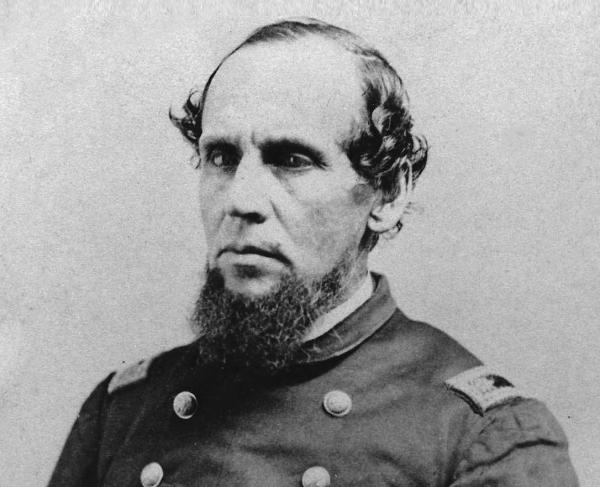

Several key figures played a role in the progression of medicine at this time. Jonathan Letterman, the Medical Director of the Army of the Potomac, brought “order and efficiency in to the Medical Service” with a regulated ambulance system and evacuation plans for the wounded. As surgeon general of the Union army, William A. Hammond standardized, organized and designed new hospital layouts and inspection systems and literally wrote the book on hygiene for the army. Clara Barton, well-known humanitarian and founder of the American Red Cross, brought professional efficiency to soldiers in the field, especially at the Battle of Antietam in September of 1862 when she delivered much-needed medical supplies and administered relief and care for the wounded. Disease and illness took a heavy toll on soldiers, but as these historic characters show, every effort was made to prevent death caused by human error and ignorance through the development of organized and more advanced practices.

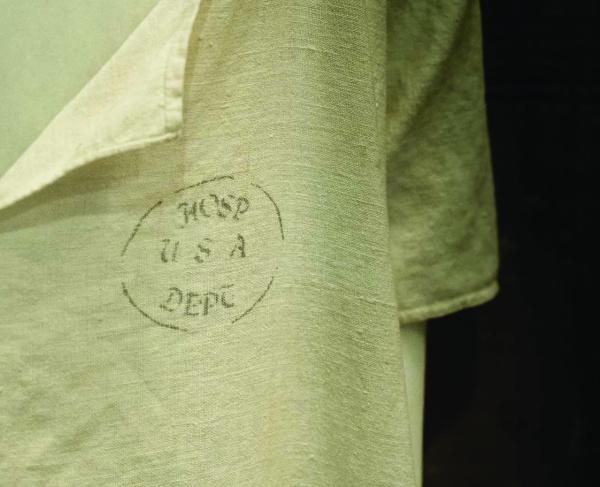

The sheer quantity of those who suffered from disease and severe wounds during the Civil War forced the army and medical practitioners to develop new therapies, technologies and practices to combat death. Thanks to Hammond’s design of clean, well ventilated and large pavilion-style hospitals, suffering soldiers received care that was efficient and sanitary. In the later years of the war, these hospitals had a previously unheard of 8% mortality rate for their patients.

Though the mortality rate was higher for soldiers wounded on the battlefield, field dressing stations and field hospitals administered care in increasingly advanced ways. Once a soldier was wounded, medical personnel on the battlefield bandaged the soldier as fast they could, and gave him whiskey (to ease the shock) and morphine, if necessary, for pain. If his wounds demanded more attention, he was evacuated via Letterman’s ambulance and stretcher system to a nearby field hospital.

Under Hammond and Letterman’s encouragement of triage organization that is still used today, field hospitals separated wounded soldiers into three categories: mortally wounded, slightly wounded and surgical cases. Most of the amputations performed at field hospitals were indeed horrible scenes, but the surgery itself was not as crude as popular memory makes it out to have been. Anesthetics were readily available to surgeons, who administered chloroform or ether to patients before the procedure. Though gruesome, amputation was a life-saving procedure that swiftly halted the devastating effects of wounds from Minié balls (which, by the way, not many “bit” to fight the pain—the chloroform usually did the trick).

In field hospitals and pavilion-style hospitals, thousands of physicians received experience and training. As doctors and nurses became widely familiar with prevention and treatment of infectious diseases, anesthetics, and best surgical practices, medicine was catapulted into the modern era of quality care. Organized relief agencies like the 1861 United States Sanitary Commission dovetailed doctors’ efforts to save wounded and ill soldiers and set the pattern for future organizations like the American Red Cross, founded in 1881.

Death from wounds and disease was an additional burden of the war that took a toll on the hearts, minds, and bodies of all Americans, but it also sped up the progression of medicine and influenced practices the army and medical practitioners still use today. While the Union certainly had the advantage of better medical supplies and manpower, both Rebels and Federals attempted to combat illness and improve medical care for their soldiers during the war. Many of America’s modern medical accomplishments have their roots in the legacy of America’s defining war.

Originally published on October 29, 2013