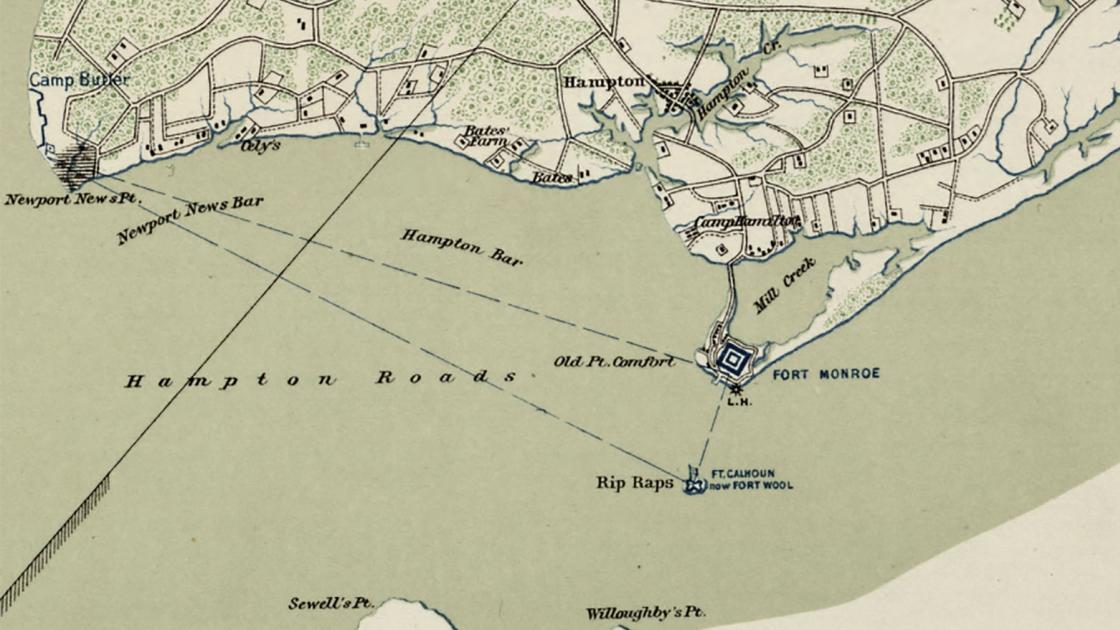

Historic Fort Wool, often colloquially known as the Rip Raps for the unusual turbulence of the surrounding waters, stands upon a small man-made island of granite at the confluence of the active Hampton Roads Harbor and the expansive Chesapeake Bay. Few locations of similar size — only eight acres — can claim to have witnessed as many important moments in American history over the last 200 years.

At the onset of the American Civil War, Fort Wool found itself a partisan political flashpoint. It had originally been named for John C. Calhoun, the revered South Carolina statesman who was secretary of war when it was commissioned. But over time, Calhoun’s political outlook evolved, and he became a champion of states’ rights over federal authority. Across the northern states, Calhoun’s name — although he was 11 years in the grave when war came — embodied the defense of slavery and the tangled path to bloodstained rebellion. On March 18, 1862, the War Department rechristened the site in honor of Brig. Gen. John E. Wool, commander of the Department of Virginia and North Carolina, based at Fort Monroe.

The thousands of annual visitors to Fort Wool look directly across the channel at Fort Monroe and its 1803 sandstone lighthouse. They stand where Robert E. Lee and Presidents Andrew Jackson, John Tyler and Abraham Lincoln once stood. They can easily imagine Fort Wool’s Sawyer Rifle cannon firing southward toward the Confederate positions on Sewell’s Point, (today’s Naval Station Norfolk). They are captivated by the westward view of the waters where the USS Monitor and CSS Virginia clashed. They are impressed by the massive granite walls and the ingenuity that built and maintained them.

Fort Wool’s architectural history melds three periods of American military construction and engineering innovation: Jacksonian-era coastal defenses constructed to protect a growing nation, concrete batteries built to house six-inch disappearing guns added in the early 20th century and Battery 229 and the Battery Control Tower, built during World War II.

Following the War of 1812, Congress authorized construction of 41 masonry fortifications to defend the nation’s coast against European attack from the sea. Fort Wool and Fort Monroe were designed to guard the entrance to the strategic Hampton Roads Harbor. Fort Monroe — located on Old Point Comfort, a peninsula created by the confluence of the James and York Rivers — built upon existing defenses dating to as early as 1609. Construction of Fort Wool’s artificial island about a mile away, across the deepwater channel, began in 1818.

At that time, Fort Wool held great promise to be an imposing and formidable defense, standing four courses high, with 232 cannon trained on the surrounding waters. On September 26, 1827, when Maj. Gen. Jacob Brown laid the first massive granite block, Baltimore-based news magazine Niles’ Register recorded the moment: “Star Spangled banner rising in majestic grandeur through the dense canopy of smoke that o’erhung the island, proclaimed to the world the birth day of another bulwark of liberty.”

Shortly after the groundbreaking, under supervision of U.S. Army engineers, more than 100 skilled stone- and brickmasons and laborers were set hard to work. Well-known satirical journalist Seba Smith noted, “not an inch of area had been reserved for a spear of grass … great cranes are erected to elevate the stone to the desired level. These are furnished with ropes, chains, pulleys, and hooks, by which stones weighing more than a ton are carried from the water edge…”

Sadly, Fort Wool’s grand design was never to be realized. The stone walls and casemates were less than half completed when it was determined that the island was settling. The government spent more than two decades bringing in sand and stone in a vain attempt to stabilize the underlying soil.

While it never realized its full potential as the envisioned bastion, Ford Wool did become a significant presidential haven. From his personal space, actually a little hut built for him on the fort’s crest, Andrew Jackson governed America for extended times from 1829 to 1837. He sought isolation at his favored retreat, “For the benefit of my health, by sea bathing, and to get free from that continued bustle with which I am always surrounded in Washington, and elsewhere, unless when I shut myself up on these rocks.”

Scores of letters from Jackson, written at Fort Wool, confirm he spent his time pondering and confronting the greatest questions of the time, including the Peggy Eaton Affair, the Bank War, the Annexation of Texas and the tragic policy of the removal of the Native Americans from their lands. Here, Jackson confronted a crisis that clearly foreshadowed the events of 1861 — John C. Calhoun’s threat to take South Carolina out of the Union. Known as the Nullification Crisis, the clash questioned the ability of states to deem federal laws void within their borders. Jackson penned in early August 1833: “In the end (nullification,) if not frowned down by every lover of liberty and government of laws, (will) destroy our happy form of government that secures to all prosperity and happiness; whilst nullification leads to disunion, wretchness [sic] and civil war.”

Jackson’s position on the matter was supported by the young second lieutenant of engineers assigned to oversee the island’s stabilization, a Virginian named Robert E. Lee. Voicing his frustration over the sectional impasse, Lee said, “There is nothing new here or in these parts, [except] Nullification! Nullification!! Nullification!!!” He was, however, less welcoming of the strong-willed president’s requested alterations, which “played the Devil” with the fort’s plan. Plagued with construction problems, he sensed that completing the fort “might be too great a labor, even for a Hercules.”

In the winter of 1861, anticipating open conflict with the South, the War Department ordered a report on the state of readiness of all the Federal coastal fortifications. In Hampton Roads, Fort Monroe was found to be “in excellent defensible condition,” though Fort Wool was “under construction; not ready for armament or garrison.” Only one course and about half of the second level of casemates were in place. Not a single cannon muzzle pointed through an embrasure. Once hostilities began, Louis M. Goldsborough, commander of the North Atlantic Blocking Squadron, called for Fort Wool to be “put in good fighting order forthwith. It is far from being in such a state just now. … The main thing is to get the place cleared away and prepared.”

Throughout the Civil War, only a handful of cannon were mounted at Fort Wool, easily the most effective of which was the Sawyer Rifle. It was pointed southward toward the strategic Confederate batteries less than two miles away on Sewell’s Point, near Norfolk, against which Fort Wool was strongly positioned.

In a late August 1861 issue, Frank Leslie’s Illustrated Newspaper circulated a field artist’s sketch of the Sawyer Rifle in action at Fort Wool. The engraving showed the thick-timbered wharf, with a Union army officer closely watching as a gunner yanks the enormous cannon’s lanyard, hurling a projectile toward the formidable Confederate positions amid a thick ring of smoke. The drawing and accompanying story attracted the notice of Northerners impatient for news of the developing war in the Tidewater region.

“The immense Rifle Cannon at the Rip-Raps (Fort Wool) thundered angrily, and to our amazement, a heavy shell exploded a few yards from us. I turned my glass at once on the Rip-Raps, and distinctly saw the muzzle of the villainous gun,” wrote novelist Augusta Jane Evans, who was visiting Confederate troops at Sewell’s Point in the summer of 1861. As she watched, the gunners reloaded and fired another “missile of death right at us…. My fingers fairly itched to touch off a red hot ball in answer to their chivalric civilities.”

In late October 1861, 11 enslaved men seeking liberty arrived at Fort Wool and reported all they knew about Sewell’s Point, providing important intelligence for the region’s defenders. They were part of a steady stream of African Americans arriving in the region since Maj. Gen. Benjamin F. Butler’s so-called Contraband Decision that spring.

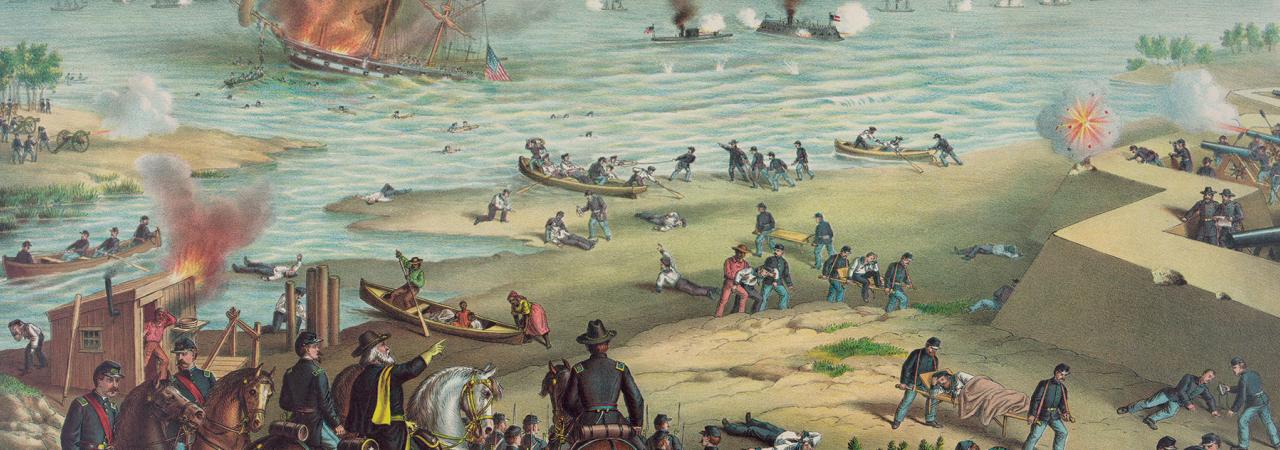

On March 9, 1862, the epic encounter between the USS. Monitor and the CSS. Virginia was fought within view of Fort Wool. At dawn, New Yorkers of the Union Coast Guard stood by, “grouped on the parapet around our cannons, spying toward Sewell’s Point and the Minnesota, yet veiled by fog.” But the Virginia was too far away for their shelling to have any damaging effect.

In early May 1862, President Abraham Lincoln came to Fort Monroe to plan the offensive movement against Norfolk and took a tugboat to Fort Wool for a close look at the rebel fortifications at Sewell’s Point. Thirty years after Jackson railed against South Carolina’s threat of secession from this rocky island, Lincoln personally ordered the firing of the Sawyer Rifle in a war for the preservation of the Union.

Abraham Lincoln used Fort Wool to watch the Federal fleet’s offensive movement. He was joined by his secretaries of treasury and war, Salmon P. Chase and Edwin M. Stanton, the latter of whom telegraphed that, “The President is at this moment at Fort Wool witnessing our gunboats. … The Sawyer Gun in Fort Wool has silenced one battery on Sewell’s Point. The James Rifle mounted on Fort Wool also does good work. It was a beautiful sight to witness the boats moving on to Sewell’s Point, and one after another opening fire and blazing away every minute.”

Today, Fort Wool has been designated a State and National Historic Landmark, but its future status is at a critical juncture. The 19th-century casemates — the same ones that sought to disable the CSS Virginia during the duel of the ironclads — are in immediate danger of collapsing. A small fissure in the brick vaulted ceiling, first noticed in Robert E. Lee’s time, has continued to expand. The WWII battery control tower (one of only two in America) is also in desperate need of stabilization. To learn more about how you can become involved in efforts to preserve this important site, contact fortwoolinfo@gmail.com.