The 19th century saw massive changes in the medical field. As a strong-willed and opinionated woman, Dorothea Dix was an active component of that change in her work as a nurse and activist, challenging notions of reform and illness.

Dorothea Lynde Dix was born on April 4, 1802, in Hampden, Maine. As a young child, Dorothea moved to Worchester, Massachusetts, to live with her...

Born on April 4, 1802, in Hampden, Maine, Dorothea Lynde Dix grew up fast. Growing up in a household where her father was gone for weeks at a time as a traveling minister, her mother struggled with her mental health. In order to survive, Dorothea completed daily chores from a very young age for her family. By the time she became a teenager, her father became more fanatic and her mother was struggling with health issues. The daily struggles and abuse that Dix experienced caused her to leave home at the age of twelve and live with her grandmother known as Madame Dix. As an adult, when asked out about childhood, Dorothea often responded with “I never knew a childhood."

While living with her grandmother, Dix became a schoolteacher and opened a school in 1821. During her time as a schoolteacher, she published Conversations on Common Things; or Guide to Knowledge: With Questions quickly becoming a popular book of facts for teachers. Ten years later, she opened a secondary school in her own home, but the demand of teaching coupled with several bouts of illness took a toll on Dix’s mental and physical health. Historians believe that Dorothea Dix suffered from depression and experienced a mental breakdown during this period spiking her interest in reform for the mentally ill. In 1836 she traveled to Europe to recover and there met several contemporary reformers including William Rathbone, prison reformer Elizabeth Fry, and the founder of the York Retreat for the mentally ill, Samuel Tuke. Returning a year later to Boston, Dix realized her passion for advocacy and reform and focused her work on improving the treatment of the mentally ill, those in prison, and the poor.

She began in 1841 by teaching Sunday School to the female inmates in the East Cambridge Jail in Massachusetts. In her volunteer work, she observed how mistreated and neglected mentally ill women were treated and strove to make a change. In 19th century America, one of the few socially acceptable ways for women to enact change was through the writing of pamphlets distributed to both government officials and the general public. In 1843, she published a “Memorial to the Legislature of Massachusetts” arguing against the treatment of mentally ill patients writing, “I proceed, gentlemen, briefly to call your attention to the present state of insane persons confined within this Commonwealth, in cages, closets, cellars, stalls, pens! Chained, naked, beaten with rods, and lashed into obedience…” The circular was a success for the government constructed separate facilities for mental patients.

Continuing her reform work, Dix visited numerous prisons and asylums throughout the East Coast and out as far west as Illinois researching the treatment of the mentally ill throughout the United States. Finding similar findings of mistreatment, over several years she produced dozens of pamphlets, reports, and memorials enacting several changes in the treatment of the mentally ill. Through these circulars, she was instrumental in the legislation needed to establish mental hospitals in New Jersey in 1845, Illinois in 1847, Pennsylvania at the Harrisburg State Hospital in 1853, and the North Carolina Dix Hill Asylum in 1856. She even took her work out of the country investigating the treatment of the mentally ill in Scotland, England, Novia Scotia, and Rome. With the beginning of the Civil War in 1861, Dix shifted her focus from mental illness and reform to nursing when she was appointed as the Superintendent of Army Nurses on June 10, 1861.

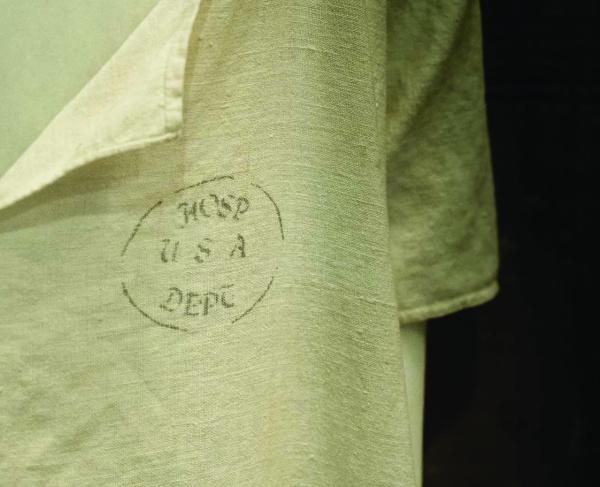

As the Superintendent of Army Nurses, Dix found herself charged with organizing and overseeing the nurses in the Union Army hospitals. She quickly earned the nickname of “Dragon Dix” with her strict and domineering approach. At the start of the Civil War, nursing was primarily a male dominated profession. The sharp and massive influx of female volunteers wanting to serve as nurses in the hospitals was not with controversy, and Dix quickly established guidelines to protect the women serving under her. In order for a woman to become a nurse, she had to be between the age of 35-50, be in good health, be of decent character or “plain looking”, be able to commit to at least three months of service, and be able to follow regulations and the directions of supervisors. Dix even went so far as to say that women had to wear unhooped black or brown dresses, with no jewelry or cosmetics.

She was very strict in her management of the nurses under her and often clashed with physicians and other volunteer groups such as the United States Sanitary Commission. In fact, the War Department passed General Order No. 351 granting Dix and Surgeon General, Joseph K. Barnes the power to appoint female nurses, and physicians the power to assign volunteers and nurses in the hospital to solve this standoff. Despite her sharp nature, she and her nurses treated soldiers from both North and South with compassion earning her a reputation after the war.

After the war, Dix returned to her work as a social reformer championing for the care of prisoners and the mentally ill. As a part of this, she reviewed asylums and prisons throughout the South evaluating their wartime damage and offering insight on how they should be redesigned. After a bout of illness, she was forced to give up her constant traveling, moving into an apartment at the New Jersey State Hospital in 1881, a hospital that she helped build. Though she was no longer traveling, she still actively wrote and advocated, writing "If I am cold, they are cold; if I am weary, they are distressed; if I am alone, they are abandoned.” Dix died in the New Jersey State Hospital on July 17, 1887, and was buried in the Mount Auburn Cemetery in Cambridge, Massachusetts.

When people think of Dorothea Dix, many first think of her role during the Civil War as the Superintendent of Army Nurses. However, outside of these four years of war, she had made bounds and leaps in the social welfare of the mentally ill and imprisoned for over forty years. She traveled and lobbied around the world, creating and improving the conditions of state hospitals for the mentally ill. Dix’s work had a tremendous impact on the medical field in the 19th century and her contributions were remembered in a variety of ways. She was elected “President for Life” of the Army Nurses Association after the Civil War, has had several parks and hospital wards named after her, was inducted into the National Women’s Hall of Fame, and had a stamp created with her likeness by the United States Post Office.

Further Reading:

- Breaking the Chains: The Crusade of Dorothea Lynde Dix By: Penelope Coleman

- Voice for the Mad: The Life of Dorothea Dix By: David L. Gollaher