Evidence for The Unpopular Mr. Lincoln

“The illustrious Honest Old Abe has continued during the last week to make a fool of himself and to mortify and shame the intelligent people of this great nation. His speeches have demonstrated the fact that although originally a Herculean rail splitter and more lately a whimsical story teller and side splitter, he is no more capable of becoming a statesman, nay, even a moderate one, than the braying ass can become a noble lion. People now marvel how it came to pass that Mr. Lincoln should have been selected as the representative man of any party. His weak, wishy-washy, namby-pamby efforts, imbecile in matter, disgusting in manner, have made us the laughing stock of the whole world. The European powers will despise us because we have no better material out of which to make a President. The truth is, Lincoln is only a moderate lawyer and in the larger cities of the Union could pass for no more than a facetious pettifogger. Take him from his vocation and he loses even these small characteristics and indulges in simple twaddle which would disgrace a well bred school boy.”

Written as Abraham Lincoln approached Washington by train for his 1861 presidential inauguration, this tirade was not the rant of a fire-eating secessionist editor in Richmond or New Orleans. It was the declaration of the Salem Advocate, a newspaper printed in Lincoln's home ground of central Illinois. The Advocate had plenty of company among Northern opinion makers. The editor of Massachusetts's influential Springfield Republican, Samuel Bowles, despaired in a letter to a friend the same week, "Lincoln is a 'simple Susan.'"

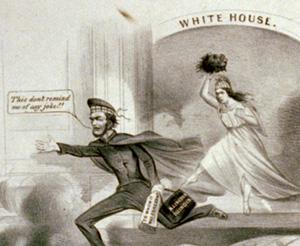

The most esteemed orator in America, Edward Everett, wrote in his diary: "He is evidently a person of very inferior cast of character, wholly unequal to the crisis." From Washington, Congressman Charles Francis Adams wrote, "His speeches have fallen like a wet blanket here. They put to flight all notions of greatness." Then, at the end of his journey a few days later, Lincoln was forced to sneak into the capital on a secret midnight train to avoid assassination, disguised in a soft felt hat, a muffler and a short bobtailed coat.

After Lincoln's unseemly arrival, the contempt in the nation's reaction was so widespread, so vicious and so personal that it marks this episode as the historic low point of presidential prestige in the United States. Even the Northern press winced at the president's undignified start. Vanity Fair observed, "By the advice of weak men, who should straddle through life in petticoats instead of disgracing such manly garments as pantaloons and coats, the President-elect disguises himself after the manner of heroes in two-shilling novels, and rides secretly, in the deep night, from Harrisburg to Washington." The Brooklyn Eagle, in a column titled "Mr. Lincoln's Flight by Moonlight Alone," suggested the president deserved "the deepest disgrace that the crushing indignation of a whole people can inflict." The New York Tribune joked darkly, "Mr. Lincoln may live a hundred years without having so good a chance to die."

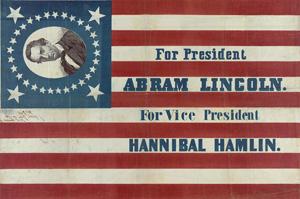

Known almost exclusively by his got-up nickname "The Railsplitter," Lincoln had won the 1860 election in November with 39.8 percent of the popular vote. This absurdly low total was partly due to the fact that four candidates were on the ballot, but it remains the poorest showing by any winning presidential candidate in American history. In fact, Lincoln received a smaller percentage of the popular vote than nearly all the losers of two-party presidential elections. Immediately, however, even this scant total dropped in the panic of the Secession Winter, as seven Southern states left the Union and worried Northerners repented their votes for the Illinoisan.

At the time he was sworn in, Lincoln's "approval rating" can be estimated by examining wintertime Republican losses in local elections in Brooklyn, Cincinnati, Cleveland and St. Louis, and state elections in Connecticut, Massachusetts and Rhode Island; by the observations of Henry Adams (of the presidential Adamses) that "not a third of the House" supported him; and by the published reckoning of the New York Herald that only 1 million of the 4.7 million who voted in November were still with him. All these indications put his support in the nation at about 25 percent — roughly equivalent to the lowest approval ratings recorded by modern-day polling.

How could a man elected president in November be so reviled in February? The insults heaped on Lincoln after his arrival in Washington were not the result of anything he himself had done or left undone. He was a man without a history, a man almost no one knew. Because he was a blank slate, Americans, at the climax of a national crisis 30 years in coming, projected onto him everything they saw wrong with the country. To the opinion makers in the cities of the East, he was a weakling, inadequate to the needs of the democracy. To the hostile masses in the South, he was an interloper, a Caesar who represented a deadly threat to the young republic. To millions on both sides of the Mason-Dixon line, he was not a statesman but merely a standard bearer for a vast, corrupt political system.

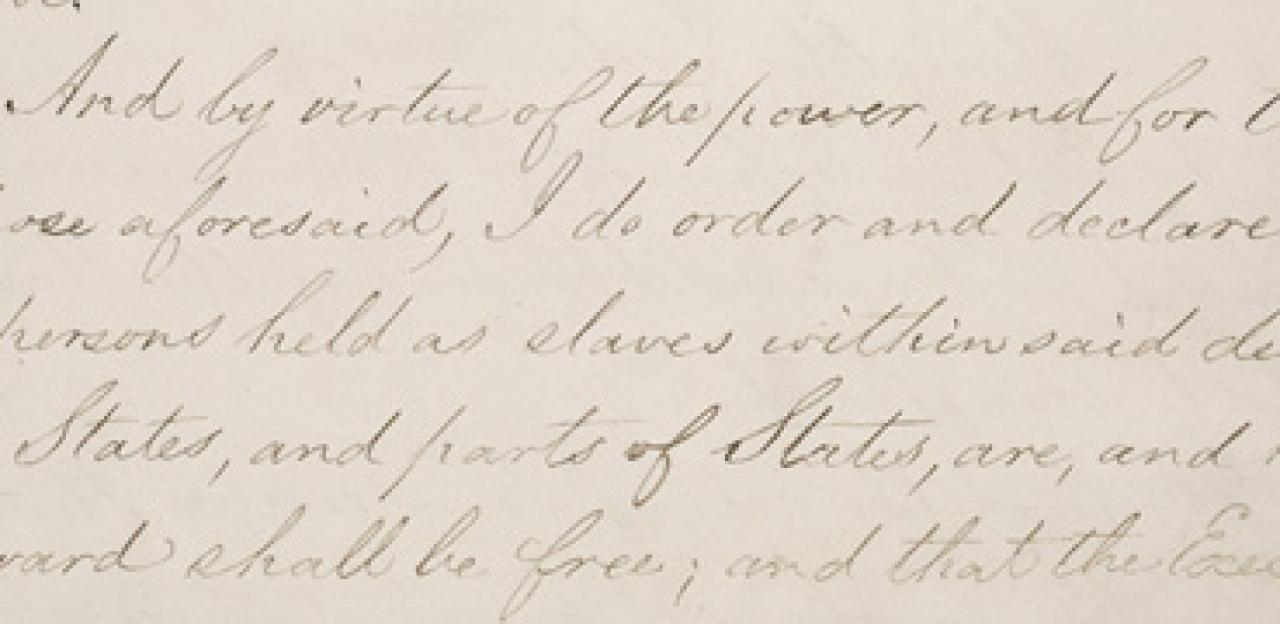

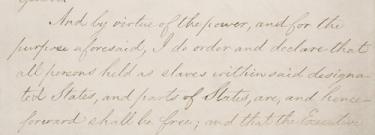

Lincoln had never administered anything larger than a two-person law office, and historians have often excused his mismanagement of the war effort during his first eighteen months in office as a period of growing into his job. It was the Emancipation Proclamation in September of 1862, according to the modern view, that signals the disappearance of the novice Railsplitter and marks the emergence of the ultimate statesman — the Great Emancipator.

This, however, was not the view at the time. The Chicago Times, for example, branded the Emancipation Proclamation "a monstrous usurpation, a criminal wrong, and an act of national suicide." An editorial in Columbus, Ohio's The Crisis asked, "Is not this a Death Blow to the Hope of Union?" and declared, "We have no doubt that this Proclamation seals the fate of this Union as it was and the Constitution as it is.… The time is brief when we shall have a DICTATOR PROCLAIMED, for the Proclamation can never be carried out except under the iron rule of the worst kind of despotism."

While the Northern press howled, angry letters piled up on Lincoln's desk and spilled onto the floor. William O. Stoddard, the secretary in charge of reading Lincoln's mail, wrote: "[Dictator] is what the Opposition press and orators of all sizes are calling him. Witness, also, the litter on the floor and the heaped-up wastebaskets. There is no telling how many editors and how many other penmen within these past few days have undertaken to assure him that this is a war for the Union only, and that they never gave him any authority to run it as an Abolition war. They never, never told him that he might set the negroes free, and, now that he has done so, or futilely pretended to do so, he is a more unconstitutional tyrant and a more odious dictator than ever he was before. They tell him, however, that his …. venomous blow at the sacred liberty of white men to own black men is mere brutum fulmen [empty threat], and a dead letter and a poison which will not work. They tell him many other things, and, among them, they tell him that the army will fight no more, and that the hosts of the Union will indignantly disband rather than be sacrificed upon the bloody altar of fanatical Abolitionism."

Indeed, there were enough angry letters home from soldiers to give color to the rumors of military revolt hinted at by Stoddard. A New York Herald correspondent attached to the Army of the Potomac felt its temper and feared for the Republic:

"The army is dissatisfied and the air is thick with revolution.... God knows what will be the consequence, but at present matters look dark indeed, and there is large promise of a fearful revolution which will sweep before it not only the administration but popular government."

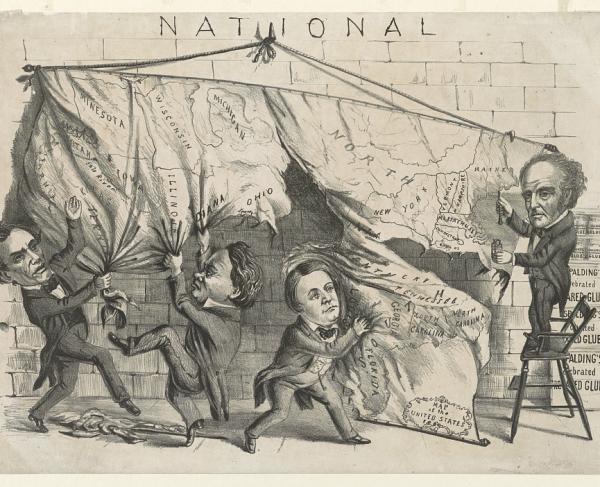

Less than two months later, in the midterm election of 1862, Northerners handed down their judgment on the Emancipator. It was a condemnation, a thumping Republican defeat — what the New York Times called "a vote of want of confidence" in Abraham Lincoln. The middle states that had swept the Railsplitter into the presidency in 1860 — Illinois, Indiana, New York, Ohio and Pennsylvania — had now deserted him. All of them sent new Democratic majorities to Congress. To them was added New Jersey, which was a Republican donnybrook. In all, the number of Democrats in the House almost doubled, from 44 to 75, cutting the Republican majority from 70 percent to 55 percent. Heartsick at the Republicans' ruin, Alexander McClure of Pennsylvania wrote, "I could not conceive it possible for Lincoln to successfully administer the government and prosecute the war with the six most important loyal States declaring against him at the polls."

When the Emancipation Proclamation went into effect on January 1, 1863, Lincoln was pilloried again in the Northern press, and desertions by disgusted soldiers climbed into the thousands. Seeing no slaves freed, even abolitionists were soured by the Proclamation's impotence. As the cold, hard rains of winter announced the approach of the third year of the war's unimaginable sorrow, Lincoln was isolated and alone. Congressman A. G. Riddle of Ohio wrote that, in late February, the "criticism, reflection, reproach, and condemnation" of Lincoln in Congress was so complete that there were only two men in the House who defended him: Isaac Arnold of Illinois and Riddle himself. Author and lawyer Richard Henry Dana, after a visit to Washington in February 1863, reported to Charles Francis Adams:

"As to the politics of Washington, the most striking thing is the absence of personal loyalty to the President. It does not exist. He has no admirers, no enthusiastic supporters, none to bet on his head. If a Republican convention were to be held to-morrow, he would not get the vote of a State."

Suddenly, warnings were everywhere that, just as Lincoln's election had sparked the secession of the South out of fear that he would abolish slavery, the Emancipation Proclamation would spark the secession of the Old Northwest — the states of Illinois, Indiana and Ohio — now that the fear had been made real. Army recruitment came to a halt in those states. In response, Congress rushed through the Draft Law, the first federal conscription act in the history of the nation. To many, the appearance of United States enrollers going from house to house was visible proof that the tentacles of Lincoln's government were curling around every American.

The popular revolt, when it reached its violent culmination, came not in the Northwest but in the nation's largest metropolis. In July 1863, in the wake of the Emancipation Proclamation and the Draft Law, riots broke out in New York City, a conflagration that, aside from the Civil War itself, was the largest insurgency in American history. Meade's victory over Lee at Gettysburg and Grant's capture of Vicksburg in the summer of 1863 stopped the erosion of Lincoln's popular support that had climaxed with the riots, but Northerners maintained a wait-and-see attitude until the spring campaigns of 1864. When spring came, the horrible carnage of Grant's Overland Campaign in the wildernesses of Virginia sent Lincoln's popularity again into eclipse.

Lincoln secured his renomination at the party convention in early June 1864, but there was no enthusiasm for him; he won by using the spoils system practice of stacking the party convention with appointees — delegates who owed their jobs to him. Attorney General Edward Bates noted in his diary, "The Baltimore Convention … has surprised and mortified me greatly. It did indeed nominate Mr. Lincoln, but … as if the object were to defeat their own nomination. They were all (nearly) instructed to vote for Mr. Lincoln, but many of them hated to do it …." The Chicago Times sneered that Lincoln could lay his hand on the shoulder of any one of the "wire-pullers and bottle-washers" in the convention hall and say, "This man is the creature of my will." James Gordon Bennett, in the columns of the New York Herald, declared, "The politicians have again chosen this Presidential pigmy as their nominee."

Things got worse over the election summer. There was the embarrassment of the near-capture of Washington in July 1864 by a rebel detachment under Lt. Gen. Jubal Early. The price of gold soared as speculators betted against a Union victory. Seeing Lincoln wounded, the Radical Republicans went in for the kill — on August 5, the New York Tribune devoted two columns to a sensational Radical declaration, known as the Wade-Davis Manifesto, that charged their own nominee with "grave Executive usurpation" and "a studied outrage on the legislative authority." It was the fiercest, most public challenge to Lincoln's — or, for that matter, any president's — authority ever issued by members of his own party. With the appearance of this surely fatal blow, everyone considered Lincoln a beaten man, including the president himself. The Democratic New York World savored the spectacle of the Lincoln's demise, reprinting an editorial from the Richmond Examiner: "The fact … begins to shine out clear," it announced, "that Abraham Lincoln is lost; that he will never be President again.… The obscene ape of Illinois is about to be deposed from the Washington purple, and the White House will echo to his little jokes no more."

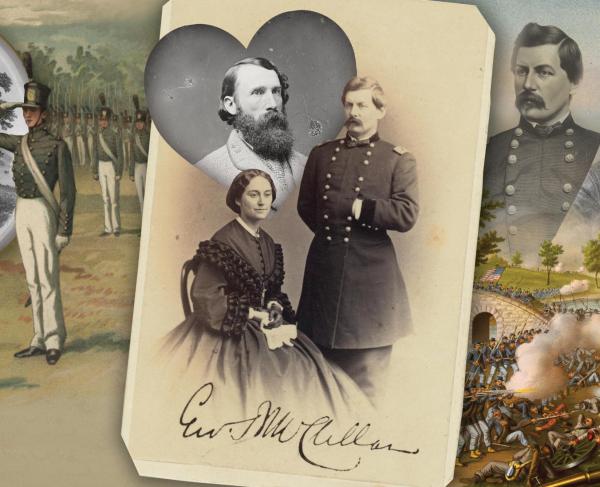

In late August, however, the Democrats nominated George McClellan on a platform that declared, "The War Is a Failure. Peace Now!" Suddenly, as bad as Lincoln may have seemed for many Republicans, he could never be as bad as McClellan. The general who battled the Republicans more fiercely than he ever had the rebels now peddled peace at any price. And then, on September 3, only three days after the Chicago convention adjourned, a second, even more amazing deliverance arrived at the White House in the form of a telegram from Maj. Gen. William T. Sherman in Georgia: "Atlanta is ours and fairly won."

Its six simple words translated a military victory in Georgia into a political miracle unequalled in American history. Senator Zachary Chandler called it "the most extraordinary change in publick opinion here that ever was known within a week." Lincoln's friend A.K. McClure sketched the election year in a stroke when he wrote, "There was no time between January of 1864 and September 3 of the same year when McClellan would not have defeated Lincoln for President." On September 4, the tide was, incredibly, reversed. The providential fall of Atlanta was followed by more Union victories in the Shenandoah Valley during September and October, and Republicans unified around Lincoln in time to win a huge electoral triumph in November: 212 electoral votes to 21.

The popular vote for Lincoln, however, was disappointing. After four years in the presidency, even in the spread-eagle patriotism of a civil war, Lincoln had only barely improved his popular showing in the North, from the 54 percent who voted for the unknown Railsplitter in 1860 to the 55 percent who voted for the Great Emancipator in 1864, when the war was almost won. In nine states — Connecticut, Maine, Michigan,

Minnesota, New Hampshire, New York, Pennsylvania, Wisconsin and Vermont — his percentage of the vote actually went down. Lincoln lost in all the big cities, including a trouncing of 78,746 to 36,673 in New York. In the key states of New York, Pennsylvania and Ohio, with their 80 electoral votes, only one half a percentage point separated Lincoln and McClellan. A shift of 38,111 votes in a few selected states, less than 1 percent of the popular vote, would have elected McClellan.

After Sherman's capture of Atlanta, a New York Republican had predicted, "No man was ever elected to an important office who will get so many unwilling and indifferent votes as L[incoln]. The cause takes the man along." Even after his reelection, plenty of Republicans were skeptical of Lincoln's contribution to the victory. According to Ohio Rep. Lewis D. Campbell, "Nothing but the undying attachment of our people to the Union has saved us from terrible disaster. Mr. Lincoln's popularity had nothing to do with it." Rep. Henry Winter Davis insisted that people had voted for Lincoln only "to keep out worse people — keeping their hands on the pit of the stomach the while!" He called Lincoln's reelection "the subordination of disgust to the necessities of a crisis." Of the seven presidential elections he had participated in, said Rep. George Julian, "I remember none in which the element of personal enthusiasm had a smaller share."

And now hatred of Lincoln developed a new, deadlier character, as dissenting Northerners and ground-under-heel Southerners woke to the awful dawn of four more years of Lincoln's "abuses." This short period culminated in Lincoln's assassination on April 14, 1865. It was only with his death that Lincoln's popularity soared. Lincoln was slain on Good Friday, and pastors who had for four years criticized Lincoln from their pulpits rewrote their Easter Sunday sermons to remember him as an American Moses who brought his people out of slavery but was not allowed to cross over into the Promised Land. Secretary of War Stanton arranged a funeral procession for Lincoln's body on a continental scale, with the slain president now a Republican martyr to freedom, traversing in reverse his train journey from Springfield to the nation's capital four years earlier. Seeing Lincoln's body in his casket, with soldiers in blue standing guard, hundreds of thousands of Northerners forgot their earlier distrust and took away instead an indelible sentimental image of patriotic sacrifice, one that cemented the dominance of the Republican Party for the rest of their lives and their children's.