John Brown’s Smoldering Spark

What do you do with John Brown?

No, not John Brown’s body … but John Brown’s anniversary. How do you deal with a body that has stopped moldering, but whose soul is still smoldering?

John Brown stabbed the United States government in 1859 over the issue of slavery. One hundred years later, in 1959 — in the midst of the Civil Rights Movement — the memory of Brown continued to prick federal policy and elicit fear within federal agencies.

In 1859, John Brown’s war raged over Harpers Ferry — and again — in 1959. Few individuals in American history have generated as much controversy and scorching debate as the fiery abolitionist John Brown. His attack on the Harpers Ferry armory and arsenal in mid-October, 1859, lasted but 36 hours. Yet the tornado spawned by his subsequent trial and execution for murder, treason and slave insurrection heaved upheaval into the consciousness of generations — now spanning three centuries.

Americans do not deliberate John Brown. Instead, we “feel” his enduring legacy. We feel the fear of the Southerner. We feel the resolve of the Northerner. We feel the anger in Dixieland. We feel the triumph in New England. We feel the rape of a culture. We feel the freedom of a race.

Saint or Madman? Murderer or Liberator? Devil or Martyr? Terrorist or Freedom Fighter? John Brown is not what we think, but what we feel.

This contrast — this geographic polarization — of feeling started almost immediately. “All Virginia [will] stand forth as one man and say to fanaticism,” bellowed James L. Kemper to fellow assemblymen in Richmond one month after Brown’s attack, that “whenever you advance a hostile foot upon our soil, we will welcome you with bloody hands and hospitable graves.”

Compare that to volcanic voices to the north in Massachusetts. William Lloyd Garrison connected Brown to the First Father of the American Republic. “Was John Brown justified in his attempt?” Garrison queried. “Yes, if Washington was in his.” Louisa May Alcott worshipped Brown as “St. John the Just.” Her neighbor Ralph Waldo Emerson enshrined Brown as “a pure idealist of artless goodness.” Henry David Thoreau reserved nothing and proclaimed Brown “the best news America has ever heard.”

Division of minds. Division of hearts. Division into parts.

“The day of compromise is passed,” announced the Charleston Mercury in reaction to John Brown. “The South must control her own destinies or perish.”

“Is it not possible than an individual may be right and a government wrong?” countered Thoreau. “Are laws to be enforced simply because they were made?”

John Brown hurled the country into conundrum. He convulsed the nation into dangerous delirium. He ensured “that North and South [were] standing in battle array.”

“If John Brown did not end the war that ended slavery,” proclaimed Frederick Douglass, “he did at least begin the war that ended slavery.”

One hundred years later, Americans could not remember the Civil War themselves, but wanted remembrance for it. For the Centennial, people predicted pageantry, parades and politicians celebrating the reunion of the country. The warriors and the war would be honored, the battlefields hallowed and the graveyards decorated.

But when would this Centennial commence?

A simple question, it seemed, with no simple answer. John Brown’s enduring specter again catapulted into the conscience of Americans, a people still divided — now not by disunion, but by disharmony.

“The people of the South would be unanimous in opposition to any celebration of the John Brown Raid,” explained Karl S. Betts, executive director of the Civil War Centennial Commission, “and most conservative people in the North would be strongly opposed to it.” Betts concluded in an interview in

September 1958, that “7/8ths of the people of the United States would look with serious concern upon such a celebration.”

And the one-eighth who would not? The African-American population.

No nation in the world practiced race segregation better than the United States in 1959. Although the Civil War had bestowed freedom for the slave, equality had not been realized. Race division was officially sanctioned by the Supreme Court 31 years after the Civil War, and nine decades after Appomattox, segregation pervaded race relations in the South and the North. After the Supreme Court reversed sanctioned segregation in 1954, the Civil Rights Movement agitated for integration, but the doctrine of separate but equal remained entrenched. Battles waged at school doors. Blood spilled on the streets. Police dogs ripped flesh. Fire hoses doused demonstrations.

The John Brown Raid “came at a bad time in 1859,” Betts proclaimed, “and conditions today are such that it would be a bad time to celebrate it in 1959.”

The Civil War Centennial Commission, established by Congress in September 1957, was created to foster public interest in the war and to encourage individual states to establish their own agencies to promote local commemorative events. Gen. Ulysses S. Grant, II, chaired the commission, and Karl S. Betts served as his day-to-day deputy. “Grant and Betts were conservatives with abundant empathy for southern whites,” discovered Robert Cook, author of Troubled Commemoration: The American Civil War Centennial. “Neither they, nor the southern state commissions, were interested in fostering public awareness of the role that blacks had played in the Civil War.”

Nor John Brown. Nor slavery. Nor Brown’s war against slavery. Any mention of slavery, in fact, must be avoided. Any observance of John Brown’s Raid “might have the effect of antagonizing the entire South to the great damage of the proposed Civil War Centennial observances,” contended Betts. He specifically demanded that the National Park Service “soft-pedal recognition of the event in 1959.”

The controversy of John Brown swiftly embroiled National Park Service officials in internal strife. The NPS had shepherded the creation of the Civil War Centennial Commission, and leaders in Washington became nervous over Betts’s warnings about doomsday reactions to any Brown observance. “Civil War Centennial Commission officials … recognize the controversial nature of the John Brown episode and the desirability of avoiding a glorification of the Raid,” acknowledged NPS Assistant Director Jackson E. Price in October 1958, adding, “we share their apprehension.” He then further informed the regional director who held bureaucratic control over the Harpers Ferry park that “the John Brown episode may be a disturbing element in engendering a bipartisan feeling.”

Feelings at Harpers Ferry already were partisan. The park’s first superintendent, Edwin M. “Mac” Dale, who arrived at Harpers Ferry from the Blue Ridge Parkway in 1956, desired to ignore John Brown. “My grandpappy was a Confederate,” Dale stammered to a NPS historian, “and we’re not going to talk about John Brown.” Superintendent Dale’s opinion ran counter to official government prospectuses dating back to 1943. “The best known event in the history of the town was John Brown’s Raid,” reported Interior Secretary Harold Ickes during deliberations to establish the site as a national monument. “Brown’s raid created violent resentment in the South and intensified sectional animosity.”

Animosity boiled over in the summer of 1957 when Superintendent Dale encountered an up-and-coming 37-year-old research historian named Charles W. Snell. Snell — who had been raised in Schenectedy, N.Y., and held history degrees from Union College and Columbia University — represented the academic antithesis of the desk-pounding, ranger-intimidating, Brownbashing superintendent. “I said to him that the national significance of the park appeared to be mainly on the John Brown Raid because this touched off the Civil War,” recalled Snell, who had been hand-selected by the regional director to “study the problems” at Harpers Ferry. Dale reacted violently, hammering his fists on a table and screaming views that re?ected a still-segregated Harpers Ferry and West Virginia, where “people around here believed John Brown was a devil.” “I was the guy,” Snell refrained, “that was selected to argue with him.”

“I explained to Mac Dale,” Snell remembered, “and later when we talked to the townspeople, that we were not making a monument to John Brown. We were going to tell the story and it would be factual. We wouldn’t say he was great or bad — that’s your opinion — form your own opinion.”

Snell departed from Dale and proceeded to the highest sanctuaries of the NPS, where he advocated his plan to restore Harpers Ferry to its John Brown/Civil War-era appearance in preparation for the John Brown Centennial. The NPS leadership boldly adopted Snell’s recommendations, and by September 1957 — the same month the Civil War Centennial Commission was established by Congress — Snell was assigned to Harpers Ferry as the supervisory historian.

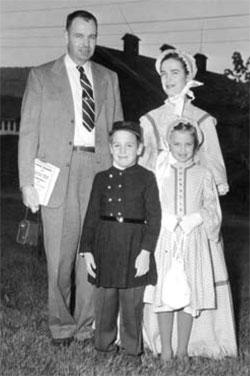

The Park Service had determined its direction regarding John Brown. Dale and conservatism were out; Snell and progressivism were in. And to ensure no interference with the Snell agenda, the Park Service replaced Dale with a ranger who had spent most of his career in the wilds of Yellowstone, far removed from the schisms of segregation. Frank Anderson arrived as the new Harpers Ferry superintendent, and Snell relished that he was “a gentleman who did not hate John Brown.”

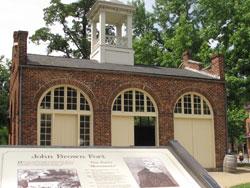

For the next year, under the tutelage of Anderson and Snell, Harpers Ferry hummed toward the Centennial. Backed by an NPS endorsement that “without John Brown (controversial though this figure may be), Harpers Ferry would probably not have meaning to the average American today,” extensive research commenced, post-Civil War buildings were demolished and the town revamped to a mid-nineteenth-century appearance. “Harpers Ferry has been thought in recent years as something of a ‘ghost town,’ gloated a magazine cover story. “Now, however, the ‘ghosts’ of the Ferry, having lain dormant since Civil War days, are waking up and starting life afresh since the U.S. Government declared their habitat a national park.”

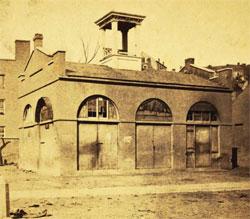

With momentum building toward the Brown Centennial, Park Service officials became giddy with excitement. “This will be our first observance of a Centennial anniversary associated with the Civil War,” exclaimed Regional Director Daniel J. Tobin in an August 1958 letter to the NPS director. Buoyed by anticipation, the Park Service commenced negotiations to acquire the John Brown Fort. The NPS coveted the former fire engine house — the only surviving building from the U.S. armory — where Brown had been captured. But it had been moved more than once and now stood on the grounds of the defunct Storer College, atop a hill more than half a mile from its original site. NPS planners dreamed of returning the fort to its home, and doing it prior to the John Brown Centennial. Time was short — only one year remained. Action must occur now.

First step — contact the Baltimore & Ohio Railroad, which owned the original site. Surely the railroad would cooperate in this mission of national import.

Subsequently, on September 17, 1958 — the 169th anniversary of the Constitution’s adoption and the 96th anniversary of the Battle of Antietam — the Park Service director sent a letter to the president of the B&O Railroad. This letter, an innocent request to obtain the actual historic site of the John Brown Fort, ignited a firestorm that engulfed the Park Service in the flaming passions of segregation.

The first B&O response looked promising. “This railroad was very much involved in activities during the raid,” effused B&O president Harold Simpson. “[The B&O] has a deep interest in Harpers Ferry as a great national monument.” Simpson even offered the Park Service contacts with the railroad real estate office. But behind the scenes, B&O executives were troubled. Attached to the September 17 letter were NPS plans for the Brown Centennial, under the title “Celebration.” That word — and its meaning — set off a spiral of controversy that convulsed the Civil War Centennial Commission and ensnared the National Park Service and Harpers Ferry in the social, cultural and political web of segregation.

Concerned the NPS was “celebrating” John Brown, the railroad brass shared its reservations with Civil War Centennial Commission members. No longer in its infancy, and now an established voice of the U.S. government, the Commission promptly expressed alarm that the Park Service would embrace Brown.

This prompted a telephone call to the NPS Chief Historian’s office from Karl Betts, Centennial Commission executive director. In this October 6, 1958, conversation, Betts expressed “serious misgivings” over the proposed John Brown observance, stating the Commission “strongly opposed” any celebration as presented in the NPS letter to the railroad. Shaken by Betts’s demonstrative declaration, the acting chief historian immediately fired off a memorandum to the NPS director. He strongly suggested that officials make it clear exactly how far the Park Service intended to go in observing the Brown Centennial — “if we still plan on having an observance now that the feelings of the Commission are known.”

The Park Service did react — in astonishing time. One week after Betts’s phone call, in a classic bureaucratic maneuver designed to mollify the segregationists and avoid the contentious clamor of the Civil Rights Movement, the agency dumped responsibility for the John Brown Centennial into the hands of the local community. Citing an obscure passage from a doctrine entitled “Policy Statement on Pageants and Reenactments,” the NPS hierarchy informed Harpers Ferry Superintendent Anderson that any commemoration of John Brown “should not be Service-sponsored but rather presented by interested groups with Service cooperation.” The NPS effectively had abandoned its role, abdicated its responsibility and divorced itself from the controversial Brown.

What was the Harpers Ferry superintendent to do?

Fortunately for history, a little group of local residents rescued John Brown and the National Park Service from the strangling noose of the Civil War Centennial Commission. With the abdication of Park Service leadership, the Harpers Ferry Area Foundation galloped into the void. Led by Chairwoman June Newcomer, the indefatigable and indefectible granddaughter-in-law of the founder of Storer College (the first school in West Virginia to educate former slaves), the Foundation planned, organized and staged a three-day “dignified observance” over the anniversary weekend in 1959. Inspired by community rather than conviction, the Foundation’s John Brown activities ranged from a serious panel discussion to a reenactment of his capture to the presentation of an original three-act play. The weekend events climaxed with a “mock battle” between Union and Confederate reenactors on Park Service property, narrated by a NPS historian, on the Bolivar Heights Battlefield.

While John Brown was the main attraction, none of these events promoted his methods, message or memory. Although Foundation planners adored Brown’s notoriety, they shunned his controversy. Although history showed slavery as a cause of the war, no one admitted it. Although a black population lived locally and in the region, few blacks participated in planning, and almost none attended activities. Although John Brown made Harpers Ferry famous, Brown’s fame was used to stake a claim and attain a gain for Harpers Ferry. “The project contemplated for Harpers Ferry,” predicted a local editor, “will ‘sell’ Harpers Ferry as no other single event has since the initial one that transpired there one hundred years ago.”

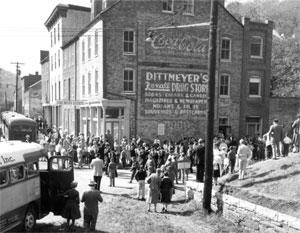

Sell it did! To the horror of the Civil War Centennial Commission, the John Brown “observance” attracted 65,000 visitors to Harpers Ferry during three stellar October days. “Not since John Brown’s historic raid has there been so much activity in Harpers Ferry,” admired one newspaper journalist. “Oddly enough, the man who descended upon the community … is the same person responsible for all the hustle and bustle going on today.”

Even worse for the Commission’s efforts to derail notoriety toward John Brown, the national media embraced the story, spreading the Brown Centennial to millions. Inspired by the David (the town foundation) versus Goliath (the Commission) struggle — and imbued with John Brown’s influence on segregation and the Civil Rights Movement — leading newspapers splashed coverage across the country. “John Brown Raids Again” proclaimed the New York Times. “The Wrathful Vintage” declared the Washington Post and “Harpers Ferry Readies for New Invasion” predicted the Baltimore Sunday American.

The undesirable publicity and the Commission’s covert segregationist policies exposed it to national ridicule. “The observance is being arranged by the local citizenry without aid or recognition by the Civil War Centennial Commission,” jeered the New York Times. “The Commission has decided that the official calendar of centennial events would not start before January, 1961.” The Washington Post joined in the jabs. “Just as John Brown jumped the gun on the Civil War with his abortive stroke against slavery, Harpers Ferry got off to a headstart on the Civil War Centennial.” And to add an exclamation point on where the Civil War commenced, the Washington Post declared: “The first shots of the Civil War Centennial were fired here today as Harpers Ferry was raided again.”

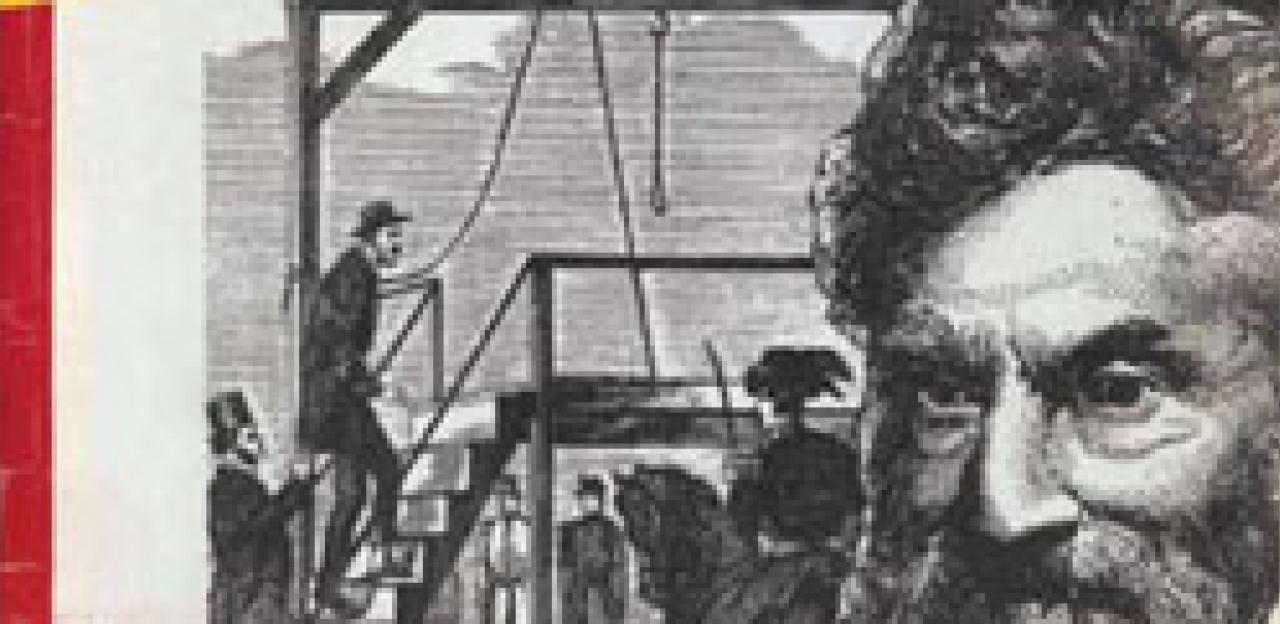

Perhaps the biggest blow to the Commission’s desire to “soft pedal” John Brown occurred when Newsweek — in conjunction with the anniversary weekend — featured Brown on its cover. With a pen and ink sketch of Brown’s portrait dramatically superimposed over a gallows, and a headline etched in bright bold red, Newsweek announced: “John Brown’s Raid: The Spark Still Smolders.”

“John Brown’s death was not an end; it was a beginning,” declared the Newsweek writer. “It fired sparks that even today smolder on the American scene.” The five-page article, featured in the center of the magazine, addressed the legend, the man, the raid and the consequences — with the bulk of the article focusing upon consequences in 1859 … and 1959.

“This week, the nation is observing the anniversary of John Brown’s Raid on Harpers Ferry,” Newsweek proclaimed. The nation. Not Harpers Ferry alone. Not the National Park Service. Not the Civil War Centennial Commission. Not the North. Not the South.

John Brown belonged to the nation … for the ages.