Lincoln's Reconstruction: An Unfulfilled Vision of the Union

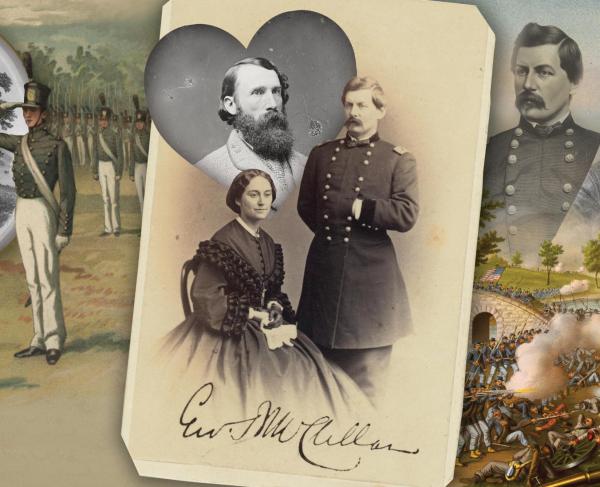

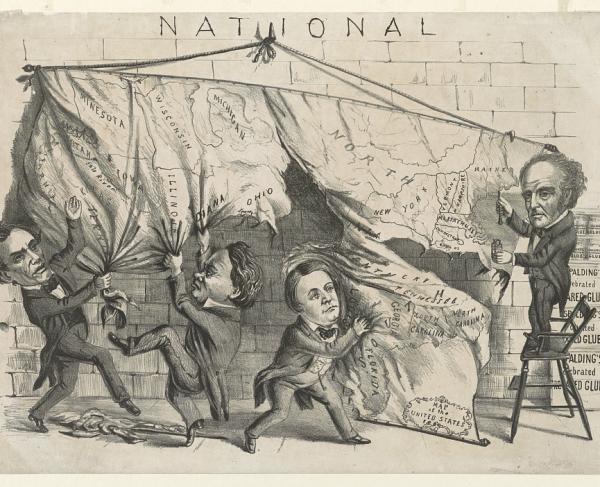

In 1861, as the Union wavered on the edge of collapse, Abraham Lincoln took office, marking the beginning of an undertaking that would test the fabric of the nation. However, before he took office, South Carolina seceded, and Lincoln’s attempts to prevent more southern states from secession proved futile; war was on the horizon. Three years later, the country now at war, General William T. Sherman, and the Union earned a crucial victory. Approaching the 1864 election, Lincoln was not in a position to win reelection. However, the fall of Atlanta, Georgia, to Union forces, boosted Union morale and helped Lincoln secure a second term in office. As Union victory became imminent, Lincoln set forth on the long path toward reconstruction, presenting in his speeches a vision of reconstruction in which the values of the American Revolution were preserved and the cause of freedom was advanced.

In his speeches during the Civil War, Lincoln envisioned a plan for reconstruction in which the elemental values of the American Revolution were preserved. When, in the fall of 1863, the Union won the Battle of Gettysburg, Lincoln delivered arguably his most famous and influential address to the Nation. Lincoln began the Gettysburg Address by referring back to the year in which the Declaration of Independence was signed, reminding listeners of the fundamental values outlined by said declaration. “Dedicated to the proposition that all men are created equal,” Lincoln said, invoking what he believed these values to be. In summoning forth the principles of a “nation, conceived in Liberty,” Lincoln reminded the Union of the foundation on which it was built. By recalling the values of the Revolution, Lincoln intended to see through that they were preserved in postbellum America. In the final moments of the Gettysburg Address, Lincoln said, “the government of the people, by the people, and for the people, shall not perish from the earth.” The phrase continued to guide Lincoln and his policy for reconstruction until his death, carrying with it his intention to preserve the government and its founding values long after the war. Lincoln’s address served to assure the distressed people of the Union that the government continued to and remain “of the people, by the people, and for the people.”

In addition to perpetuating the revolutionary values of the United States, Lincoln promoted his vision of a “more perfect Union” by presenting a path for reconstruction in which freedom would be advanced. After the Emancipation Proclamation was signed on January 1, 1863, Lincoln’s rhetoric shifted from preserving the Union to furthering equality by extending freedoms, although severely limited, to Black Americans. “It may seem strange that any men should dare to ask a just God’s assistance in wringing their bread from the sweat of other men’s faces,” Lincoln said in his Second Inaugural Address, confronting the hypocrisy of slavery. In his speech, Lincoln asserted that “American slavery is one of those offenses” for which God punished both the North and South. Thus, the war was repentance for that sin. Lincoln, in making this statement, recognizes that the path forward must not be characterized by the same hypocrisy for which the war was fought. He expands on this idea in his Last Public Address, wherein he argues reconstruction should portend new freedoms. Along with supporting the newly established Louisiana government’s request to join the Union, Lincoln supported the Louisiana government’s decision to “give the benefit of public schools equally to black and white” and extend, although limited, “elective franchise” to Black men. In the last moments of his last public address, Lincoln lauded these decisions and called for Louisiana to be the example for reconstruction. Lincoln was on the verge of creating the “new birth of freedom” he envisioned in his Gettysburg Address. However, his plans were cut short on April 14, 1865, and his vision for reconstruction was not realized.