The Long, Gruesome Fight to Capture Vicksburg

U.S. Navy Cdr. David Dixon Porter was not a complacent man, and his patience was put to the test in November 1861, as he waited through the morning outside the office of the Secretary of the Navy, Gideon Welles, hoping for an audience.

Porter knew he wasn’t Welles’s favorite commander. Porter’s brashness led him to follow his own instincts more rigorously than orders, which did not sit well with the white-bearded member of President Abraham Lincoln’s cabinet. In any case, it wasn’t easy for an officer of his rank to attain a meeting with the secretary.

But Porter had devised a bold plan to capture New Orleans and Vicksburg. If successful, it would claim the Mississippi River for the North. It had been seven long months since the Confederates had attacked Fort Sumter, and nothing had been done to seize control of the river that was the lifeline of the South. How could the administration ignore it? Time was wasting, and the Confederates were no doubt fortifying their strongholds up and down the river.

As Porter waited, along came two senators — James Wilson Grimes of Iowa and John Parker Hale from New Hampshire — who asked about his recent service on the Gulf Coast. Porter wasted no time telling them of his plan to capture New Orleans, and “how easily it could be accomplished.”

The senators were surprised no such action had been taken. At once, they gained access to Welles. Porter described his plan “in as few words as possible,” and Welles said they should see the president immediately. The group proceeded to the White House, and were ushered in to see Lincoln.

“This should have been done sooner,” Lincoln said upon hearing the plan. “The Mississippi is the backbone of the Rebellion; it is the key to the whole situation. While the Confederates hold it, they can obtain supplies of all kinds, and it is a barrier against our forces. Come, let us go see General [George B.] McClellan.”

The expanding group, soon joined by Secretary of State William Seward, proceeded to the headquarters of the commander of the Army of the Potomac, who was at the height of his power and influence. The president left it to McClellan and Porter to work out the details, but Lincoln could not help but add his expertise on the subject. This was his country, his river. In 1828, at age 19, he had crewed a flatboat full of meat, corn and flour on a 1,200-mile journey to New Orleans down the Ohio and Mississippi Rivers, earning $25.

“See what a lot of land these fellows hold, of which Vicksburg is the key,” Porter recalled that Lincoln lectured, pointing to a map. “Here is the Red River, which will supply the Confederates with cattle and corn to feed their armies. There are the Arkansas and White Rivers, which can supply cattle and hogs by the thousands. From Vicksburg, these supplies can be distributed by rail all over the Confederacy. Then there is that great depot of supplies on the Yazoo. Let us get Vicksburg and all that country is ours. The war can never be brought to a close until that key is in our pocket. I am acquainted with that region and know what I am talking about, and valuable as New Orleans will be to us, Vicksburg will be more so. We may take all the northern ports of the Confederacy, and they can still defy us from Vicksburg.”

In the South, Confederate President Jefferson Davis held the same opinion. "Vicksburg is the nail head that holds the South’s two halves together,” he said. It is “the Gibraltar of the West.”

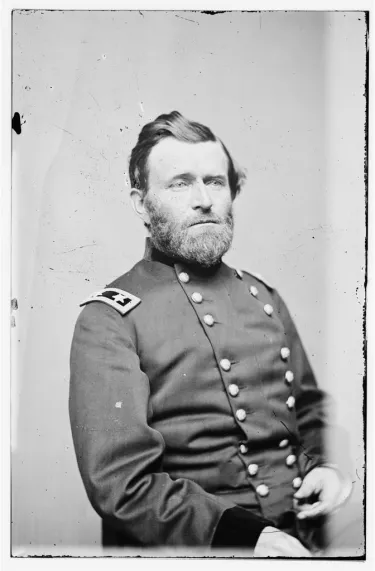

As Lincoln spoke on that November day, surely none of the men in the room thought it would take almost two more years and one frustrating setback after another before the key to Vicksburg was finally in the president’s pocket. Ultimately, it would become the prize of Ulysses S. Grant — a cornerstone victory in his legacy as the greatest Union commander of the Civil War. But almost another full year had to pass before Grant even become involved.

It took months of planning and preparation, but on April 25, 1862, the Federal fleet sailed into New Orleans, capturing it for the North. With Porter commanding a mortar fleet and Flag Officer David Glasgow Farragut in command of the overall fleet, the federal ships pressed on, snaking the 400 miles upriver to Vicksburg, arriving May 18. Farragut’s demand for the city’s surrender was formally rejected by the city’s military commanders, as well as the mayor.

Two days later, the Union flagship Oneida fired the first shot — a rifled projectile aimed at a column of marching Confederate troops. The entire city then waited in nervous suspense for six more days before Farragut acted again. On May 26, his warships sent about 20 shells streaking into the city, with even more on the following two days, as residents huddled in basements and caves in the flickering glow of candles or kerosene lamps.

The Confederates saved their ammunition, with the bonus that their strategy also served as a sign of contempt for the threat posed by the Federal fleet. Farragut withdrew to New Orleans, a move that displeased Lincoln and outraged Welles. A chastened Farragut, now doubly determined to capture the city, again steamed upriver, arriving with even more ships and 3,000 troops on June 25. A second Union fleet came south from Memphis, Tenn. Lincoln himself issued the demand that Farragut join the two fleets. To do that, he would have to run the daunting land batteries on the heights of Vicksburg.

Although situated hard on the river, Vicksburg’s tall bluffs and hills protected it from the capricious floods of the mighty waterway. It was the “city of a hundred hills” a local newspaper editor wrote, and local folks usually spoke of going “up” or “down” to visit neighbors. The hills provided a tremendous natural defense, as well as a multitude of perches from which Confederate artillerists could bombard the Union vessels.

On the afternoon of June 26, Farragut’s guns opened up on the city, firing night and day for the next two days to soften its defenses, but the shells did little damage.

Undaunted, Farragut pressed forward in the dark, early morning hours of June 28. When Confederates guns began firing on the approaching ships, the Union naval officer unleashed a torrent of shot and shell, sending residents scurrying for cover as hot iron shrieked into the city. Confederate gunners, itching for months to pull their lanyards, blazed away at the fleet in a wild scene of river combat. “I never saw such a magnificent spectacle in all my life,” wrote one Union sergeant watching aboard a waiting transport.

By first light, all but three vessels had run the batteries unscathed and only one of those was significantly damaged. Farragut lost 15 dead and 30 wounded; two Confederates were killed and three wounded. The dramatic engagement proved again that warships could rather easily pass powerful land batteries, and Farragut was able to join the fleet from the north. But it also demonstrated that Vicksburg could not be taken by naval power alone.

Perhaps, then, the stronghold could be bypassed altogether. Vicksburg sat just below a 180-degree bend in the Mississippi River. That U-turn created the DeSoto Peninsula, which sat directly across from the city. The day before Farragut’s passage, Union troops and some 1,000 slaves who had been promised their freedom began digging a canal that was to stretch a mile and a half across the base of the narrow peninsula. But it was summer, and the river fell faster than the men could dig the canal deep enough to flood. By mid-July, the project had been abandoned. Once again, the Union forces were out of options. Their 3,200 infantrymen could ill afford to try to assault those high river bluffs, with five times their number waiting at the top.

On July 15, the plucky Southern defenders delivered another blow when, with sudden fury, a single Confederate ironclad, the CSS Arkansas, sailed down the Yazoo River north of the city and attacked three Union vessels, seriously damaging one, before entering the Mississippi above Vicksburg. The Arkansas then took on the Union fleet, pouring a barrage of shells into Farragut’s flagship, the Hartford, and another vessel.

Inflicting far more damage than it received, the Confederate warship limped to the landing at Vicksburg, its Confederate flag flying from a makeshift pole as jubilant citizens wildly hailed its arrival. A furious Farragut counterattacked that very evening, once again steaming past the belching land batteries, but failed to sink or destroy the Arkansas. Another attack with two ships on July 22 also failed.

Once again, Union efforts had been stymied, and on July 24, Farragut withdrew back to New Orleans. The challenge of conquering Vicksburg seemed insurmountable.

“Our combined fleet lay there and gazed in wonder at the new forts that were constantly springing up on the hill tops … while water batteries seemed to grow on every salient point,” Porter wrote. “It was evident enough that Vicksburg could only be taken after a long siege by the combined operations of a large military and naval force.”

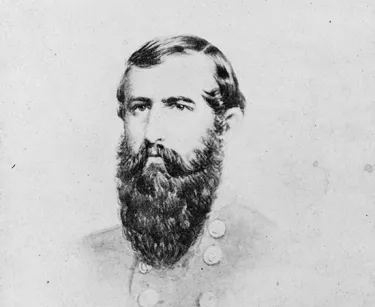

The guns at Vicksburg fell silent for the moment, but on October 25, Grant assumed command of the federal Department of the Tennessee and began the long-desired overland campaign against Vicksburg. That same month, Confederate Lt. Gen. John C. Pemberton was put in charge of defending the seemingly all-but-impregnable city.

Both commanders had distinguished themselves in the Mexican War. While Pemberton had served in the Confederate army on the mid-Atlantic coast in 1861 and 1862, Grant had returned to Union service in June 1861 as a colonel of a regiment, but had steadily risen in stature following his capture of Fort Donelson in February 1862 and his bloody but triumphant action at Shiloh in April.

With characteristic promptness, Grant marched into Mississippi and occupied Holly Springs on November 29, 1862, establishing a supply depot there. Already underway, however, was a strange new development that would complicate his job.

In September, former Illinois congressman and Brig. Gen. John A. McClernand paid a visit to his fellow Illinoisan in the White House and convinced President Lincoln to let him raise a new army of fresh recruits in the west and launch a campaign to capture Vicksburg. Lincoln agreed, even though he knew Grant was already beginning his own campaign. Moreover, Grant was not informed; he found out only as McClernand’s new recruits poured into the Union base at Memphis.

Grant and Maj. Gen. William Tecumseh Sherman decided to take the new recruits, as well as Sherman’s existing force, and transport them to Vicksburg via the Mississippi, accompanied by the fleet of David D. Porter, now an admiral. On December 20, Sherman’s 32,000 men left Memphis aboard approximately 100 transports.

At dawn on that very day, 3,500 Confederate horsemen under Maj. Gen. Earl Van Dorn came pounding out of the woods around Holly Springs, shrieking the Rebel yell, and galloped into the town from all directions. Grant was further south in Oxford, but most of the 1,500 Federals at the garrison were captured and Van Dorn’s raiders torched $1.5 million in supplies and stores.

Grant had no choice but to withdraw back into Tennessee as Sherman and Porter continued on despite the setback. Sherman’s men disembarked on the Yazoo River above Vicksburg on December 26 and, for the next three days, pelted by rain, they slogged through swampy bottom lands before reaching Chickasaw Bayou and the heavily defended bluffs north of the city. On December 29, after an artillery barrage, Sherman’s men assaulted the bluffs. They were repulsed, suffering more than 1,700 casualties, almost 10 times the number of Confederates who fell. Sherman planned another assault for New Year’s Day, but awoke to find the landscape fogged in. He had no practical choice but to disengage.

Sherman’s report was as spare as an official report could be: “I reached Vicksburg at the time appointed, landed, assaulted and failed, re-embarked my command unopposed and turned it over to my successor.” The successor, none too pleased, was McClernand, who had arrived from Memphis, demanding his missing army.

Vicksburg seemed more impregnable than ever. A series of five operations from January to March 1863 — Grant called them “experiments” — succeeded only in underscoring the city’s strength through their failure. Porter almost lost his fleet trying to forge a path in the tangled bayous north of the city. To try to get his boats and men below Vicksburg without passing the batteries, Grant resumed the canal construction on the DeSoto Peninsula, as well as at two other locations. The doomed and now-flooded canal project was derided in the press as Grant’s “Big Ditch.”

His fortunes were at a low point and press criticism at a peak in early 1863, but Grant’s resolve was unbowed. He arrived at the Union base at Young’s Point, across from the mouth of the Yazoo River, on January 29 and took personal command of all the forces — some 45,000 men. He relegated McClernand to command of a corps, put Sherman in charge of another corps and Maj. Gen. James B. McPherson in charge of a third. Being bombarded by criticism as he was, Grant did not want to turn around, withdraw to Memphis and try another overland campaign from northern Mississippi. He knew an assault on the city and its bluffs from across the river would be far too costly, if not impossible. He decided on another approach.

On March 29, Grant marched most of his army south through Louisiana, skirting Vicksburg some 10 miles to the west, before stopping across from Grand Gulf, Miss. Grant knew he would need Porter’s ships to get his men across the river, and on the night of April 16, in another dramatic spectacle, Porter took 12 vessels past the bluffs of Vicksburg and their blazing guns. All but one safely made it past. On April 22, six transports and a dozen barges ran the batteries. Half the barges and a transport were lost, but the rest made it.

Porter attacked the Grand Gulf forts on April 29, but failed to silence a gun, so Grant simply marched his men a bit further south and the next day crossed the Mississippi at the tiny river town of Bruinsburg.

On May 1, successfully across the river, “I felt a degree of relief scarcely ever equaled since,” Grant wrote in his memoirs. “Vicksburg was not yet taken it is true, nor were its defenders demoralized by any of our previous moves. I was now in the enemy’s country, with a vast river and the stronghold of Vicksburg between me and my base of supplies. But I was on dry ground on the same side of the river with the enemy. All the campaigns, labors, hardships and exposures from the month of December previous to this time that had been made and endured, were for the accomplishment of this one object.”

Now Grant began to move more quickly. He broke from his base, knowing from the earlier overland campaign that his men could largely live off the land in Mississippi. His troops defeated the Confederates at Port Gibson, 30 miles south of Vicksburg, in a small but mean fight on gnarled terrain. Then, instead of engaging Vicksburg from the south, Grant decided to march his men 60 miles northeast to the state capital, Jackson, and attack the Confederate forces there first, preventing them from supporting Pemberton at Vicksburg and cutting off the vital rail connection from the east.

The Federal forces defeated the outnumbered Confederates in an engagement at Raymond on May 12 and captured Jackson after another clash on May 14. Pemberton’s troops marched out of Vicksburg to meet Grant and, two days later, the armies fought at Champion Hill, which changed hands three times before the Confederates were routed. After another engagement at Big Black River Bridge on May 17, Pemberton’s men fell back in disarray to their defenses at Vicksburg, and Grant arrived at the city’s outskirts.

Grant could have laid siege right then, but his men were flying high with confidence. Gone were the hard, fruitless days of the winter. They had met every challenge so far in Mississippi, and with the Confederates on the run, Grant had every reason to think that a strong, concerted attack would conquer the city right then and there.

By May 19, Grant’s troops were spread out along the outskirts of Vicksburg in a line that stretched for miles. That afternoon, Grant launched an assault against the imposing fortifications guarding Vicksburg. Most of the attackers were cut down by the murderous Confederate fire, but some reached the ditches in front of the fortifications and planted their flags on the sides of the walls. They got no farther.

Three days later, Grant tried again with a massive assault along more than three miles of lines. All along the front — at Stockade Redan, and the Great Redoubt, at the Second Texas Lunette and the Railroad Redoubt — Union attackers fought to breach the Confederate defenses, and succeeded here and there in gaining tiny footholds, only to be thrown back, sometimes after savage hand-to-hand fighting.

“The attack was ordered to commence on all parts of the line at ten o’clock a.m. on the 22nd with a furious cannonade from every battery in position,” Grant wrote. “The attack was gallant, and portions of each of the three corps succeeded in getting up to the very parapets of the enemy and in planting their battle flags upon them; but at no place were we able to enter.”

Grant lost about 1,000 men on May 19, and another 3,100 on May 22. Confederate losses on both days totaled less than 1,000. The dead and wounded from the second assault lay between the lines for two days and the pall of death hung heavy over the city. The ghastly scene prompted Pemberton to ask for a two and a half hour truce to bury the dead on May 25.

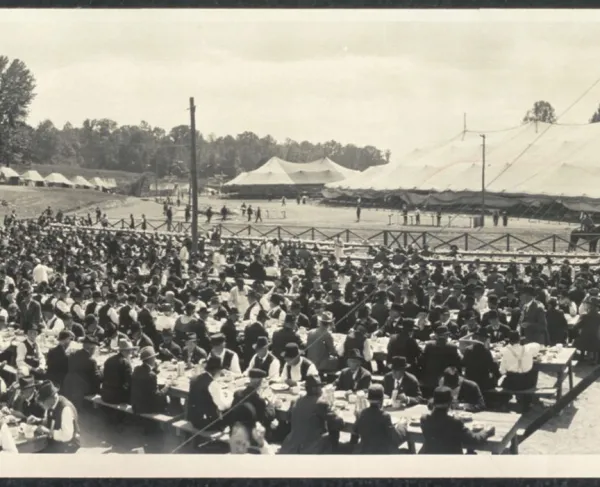

The truce that evening spawned one of the most amazing moments of the war as combatants on both sides emerged to talk and jaw, and trade stories and rations. Two brothers, one from each side, were said to have met halfway between lines. One Union officer said he saw four soldiers playing cards — two Yankees and two Rebels. Sherman met with a Confederate officer to give him a handful of letters from his Northern friends addressed to Southern officers and men.

Soon the truce ended, and the heavy mortars and artillery began to boom once more as bombardment of the city resumed. It would continue for days on end, while Grant tightened the noose around the river city.

“I now determined upon a regular siege — to ‘out-camp the enemy,’ as it were, and to incur no more losses,” Grant wrote. “The experience of the 22nd convinced officers and men that this was best, and they went to work on the defenses and approaches with a will. With the navy holding the river, the investment of Vicksburg was complete. As long as we could hold our position, the enemy was limited in supplies of food, men and munitions of war to what they had on hand. These could not last always.”

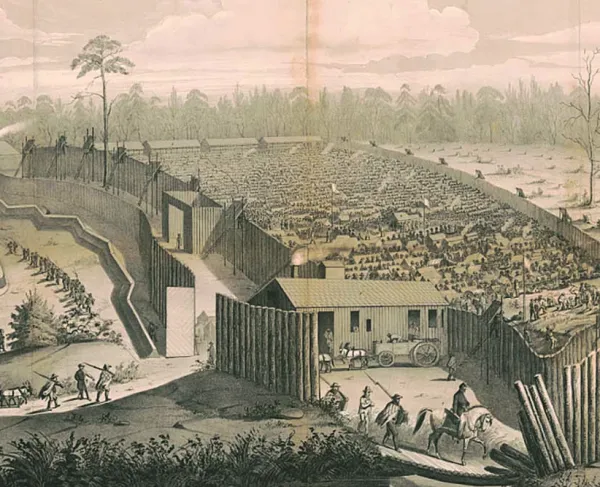

Pemberton said he had about six weeks of supplies for his army of some 30,000 men as well as the civilian populace of Vicksburg, which proved to be an excellent estimate. Grant’s men, meanwhile, did not remain idle, digging tunnels to the Confederate lines and under their fortifications. On June 25, Union engineers exploded a massive mine under the 3rd Louisiana Redan, and Federal troops poured into the crater. For a full day they fought to maintain the breach in the Rebel line, but finally fell back.

In Vicksburg, supplies of all stripes became first scarce, then nonexistent. The citizenry became used to living in caves to protect themselves from the incessant bombardment, and doing little more than trying to survive each day.

“We are utterly cut off from the world, surrounded by a circle of fire,” wrote Dora Miller in her diary on May 28. “Would it be wise like the scorpion to sting ourselves to death? The fiery shower of shells goes on day and night. People do nothing but eat what they can get, sleep when they can and dodge the shells.…I send five dollars to market each morning, and it buys a small piece of mule meat. Rice and milk is my main food. I can’t eat the mule meat.”

It would get far worse. On July 3, she wrote that “rats are hanging dressed in the market for sale with mule-meat; there is nothing else.”

If Pemberton harbored hopes of breaking out of his trap, by July 3, his men were too famished to effectively fight. His only option was surrender. That afternoon, the two generals met between the lines under an oak tree. At almost the same moment, some 15,000 Confederates were charging up Cemetery Hill during Pickett’s Charge on the climatic third day of the Battle of Gettysburg.

Both moments of triumph for the Union had been months in the making, but in a single day, the Confederate States of America went from a viable political enterprise to a lost cause. Grant cemented his stature as the North’s greatest general, and in 1864 he would be elevated to command of all of the Union forces.

In Washington, the fate of the Union was finally looking brighter to President Abraham Lincoln. “The signs look better,” he wrote the following month. “The Father of Waters again goes unvexed to the sea.”