Azel Woodworth was only 15 years old when he served at the Battle of Groton Heights in 1781. After enlisting the previous year in Captain William Latham’s matross company, which assisted in loading, firing and sponging guns, Woodworth helped defend Fort Griswold from invading British troops — until a musket ball struck his neck, just under his right ear, and exited along his spine, cutting through skin, muscles, tendons and bone. As Woodworth later recalled, the injury rendered him “insensible” for a “short interval.” Then, he “partially recovered” and resumed military action. The following day, however, his mental “faculties retired” and “returned not for 24 hours.” Woodworth’s wound not only caused his head to permanently rest on his left shoulder, but also significant intellectual incapacity that waxed and waned over the course of his life.

Woodworth’s injuries to his head, neck and intellect dramatically altered the adulthood he had imagined for himself at the age of 15. As he later wrote in a memoir — which was reprinted in William Wallis Harris’s The Battle of Groton Heights: A Collection of Narratives, published in 1870 — due to Woodworth’s “deranged state,” his father stopped teaching him a trade, believing that he would be “unable to progress in the study.” Even manual day labor, which Woodworth pursued as a result, “exhausted” his “mental faculties,” causing him pain and requiring frequent breaks. In the 1790s, the veteran married, had two children, and pursued a business in husbandry. Yet his difficulties in laboring soon led to financial troubles. Despite receiving a small monthly “invalid” pension of $1.66 from the newly formed federal government in 1794, by 1807 Woodworth had become a self-described “wandering person” dependent on the “charity of fortuitous friends.”

Not much has been written about Revolutionary War veterans with intellectual impairments. In part, this is a product of the lack of existing source material. The archive of federal and state invalid pension applications and materials offers rich insight into veterans’ wartime and civilian experiences; however, officials mandated that applicants prove “decisive disability” caused by “known wounds,” a stipulation that privileged veterans with physical injuries over those with intellectual challenges. The loss of an eye or a limb was significantly easier to demonstrate to judges, officials and the family members and neighbors who testified on behalf of pension applicants as compared with symptoms such as irritability, memory lapses or fears of impending doom. As a result, invalid pension claims, such as Woodworth’s, which document intellectual disabilities arising from the war, are relatively rare. Woodworth’s surviving personal narrative makes his case even more unique.

Examining Woodworth’s case and the few other veterans with intellectual ailments in the federal invalid pension archive suggests the significant toll the war took on veterans’ minds as well as their bodies. These records reveal veterans struggling to work, gain economic security, reenter their communities and maintain their expected patriarchal positions in their households. We also see evidence of what might now be diagnosed as post-traumatic stress disorder: men described by others as “lost,” “speechless,” “bewildered” and “delirious.” Even so, some scholars have suggested that Revolutionary War veterans with disabilities did not experience significant prejudice or exclusion as a result of their injuries. In a study of service pensions issued in 1820, Daniel Blackie concluded that Revolutionary War veterans with and without disabilities had similar levels of poverty. Yet focusing on veterans with intellectual impairments suggests greater challenges, possibly because of deep prejudices toward intellectual disability in early national American society.

Indeed, while intellectual disabilities had long been stigmatized in the American colonies, in the context of the new republic such incapacities were viewed as especially threatening. According to Kim E. Nielsen in A Disability History of the United States, in the colonial period, “physical disability was largely routine and unremarked on,” but those “we would categorize [today] as having psychological or cognitive disabilities attracted substantial policy and legislative attention” as officials sought to protect communities from the perceived costs of their support. After the Revolution, fears about the dependency of intellectually disabled people heightened. The United States was founded on the premise that rational citizens were capable of voting and making reasoned political decisions. Intellectual disability seemed to threaten the national experiment. Employment incapacities arising from mental ailment also seemed to compromise the nation’s economic robustness. As a result, citizens with cognitive impairments faced intensified legal and political exclusions, including from suffrage, as well as the threat of institutionalization toward the mid-19th century.

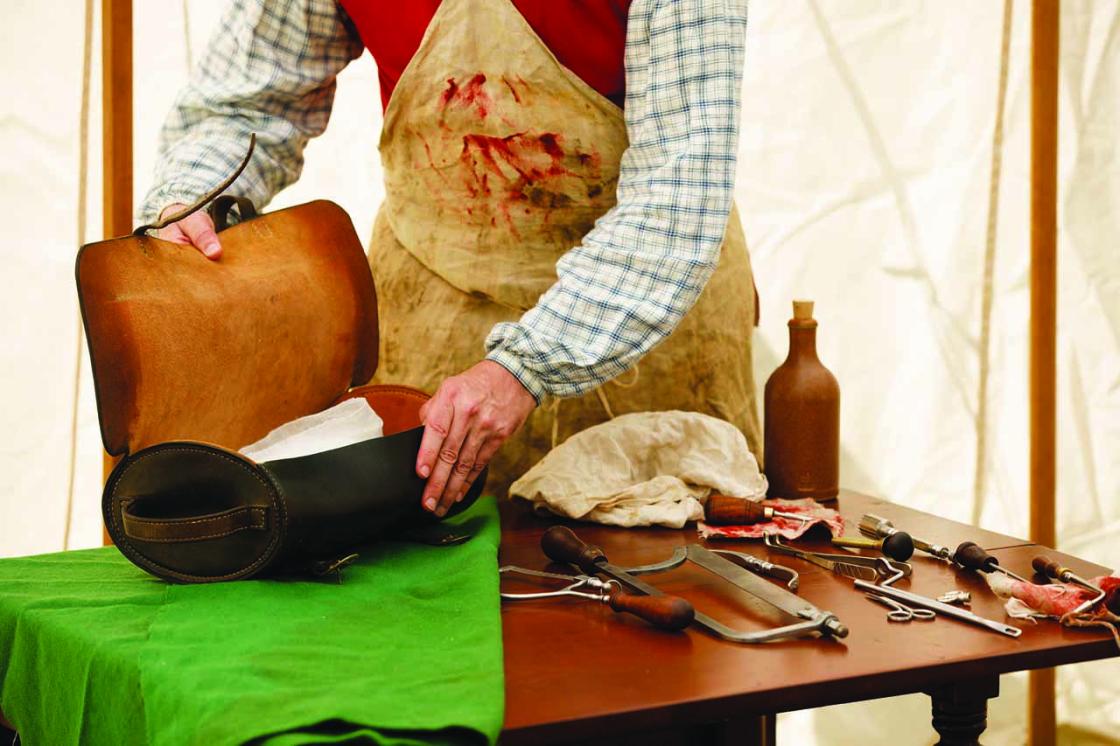

Veterans with intellectual disabilities felt the brunt of these developments; however, not all servicemen’s stories were as harrowing as Woodworth’s. Some veterans with intellectual difficulties benefited from networks of family and community care. After Richard Watrous, a private in the Sixth Connecticut Regiment, was wounded in the Battle of Norwalk in 1779, he received intensive and prolonged support from fellow soldiers, doctors, family members and townspeople. Watrous was injured in his arms and torso by musket balls and bayonets, causing fractures and wounds, as well as disturbances to his mental state. As neighbors explained, he “appears to be lost & bewildered” much of the time, perhaps owing to “some radical injury to his constitution.” Watrous was first cared for by servicemen and former neighbors, then by physicians and military officers, and finally by family and community members at home. As one neighbor recalled, an officer “assured me [that Watrous] Should have all Possible Care taken of him,” a support that eased the veteran’s mental and corporeal struggles until his death in 1799.

Despite such networks of care, men with intellectual impairments often struggled to remain employed and maintain financial security. Certainly, the waves of economic depression and recession following the Revolution, together with the federal government’s payment of military salaries and pensions in depreciating Continental dollars, created hardships for all veterans, disabled or not. Yet those with intellectual ailments seemed to face special challenges in their efforts to work and gain a livelihood. Cornelius Hamlin, a Connecticut corporal who experienced “fits” and “fatigue,” wrote in his pension application about his struggle to continue his carpentry business — hiring workers, pushing his own body to the limit and ultimately reducing his business to a fraction of its previous worth. Toney Turney, one of the few African American veterans who received a federal invalid pension, also described employment hardships, which were perhaps especially pronounced for the formerly enslaved man. According to a neighbor, Turney’s complications from his head wound rendered him “often Laid by” and “unable to support himself.”

In some cases, men’s descriptions of their cognitive ailments seem to mirror what psychologists would now describe as post-traumatic stress disorder. Scholars are rightly wary of diagnosing people in the past with modern medical conditions. Historical people experienced and perceived bodily and intellectual impairments differently from people today, making retrospective diagnoses not only unhelpful and misleading, but also potentially damaging. And yet some Revolutionary War pension claims do document men, such as Watrous, who were “lost & bewildered” as well as those whom judges described as having “derangement of mind,” “impaired” sense, memory difficulties and violent outbursts. Take one illustrative case: In 1794, a New Hampshire judge appended the following note to Amos Pierce’s pension application: “Soon after his return from service, he was taken speechless, which has ever since, in a great measure continued.” Pierce is nearly always “in a state of delirium,” the judge went on, although he noted that doctors were unclear whether these symptoms stemmed from his physical wounds. Accounts such as Pierce’s suggest the significant effects of the war on veterans’ mental states.

Many Revolutionary War veterans with intellectual impairments struggled to labor in their households and communities and reenter civilian life. Such challenges were likely partly due to the realities of their injuries; they were also a product of a society deeply prejudiced against people with intellectual disabilities, whom many Americans without a disability viewed as dependent, unfit for civic responsibilities, and increasingly, proper subjects for institutions. When Azel Woodworth wrote about his challenges to find work and support his family over the course of his life, he commented that he had finally “retired in confusion & despair from all I held dear on earth.” Such sorrowful sentiments testify to the significant difficulties that Revolutionary War veterans with intellectual ailments, including what might now be termed post-traumatic stress disorder, faced. Their stories, today nearly 250 years old, urge us to push for greater recognition and support of veterans experiencing such conditions in the present. In addition, stigma against mental illness and intellectual disability has persisted, imploring us to work to dismantle ableism today.