Today many take the modern field of medicine for granted. Doctors have an extensive knowledge of diseases and advanced medical procedures, and most patients have access to hospitals and medicines treating several kinds of illnesses and injuries. However, medicine in the 1700s was drastically different than it is today, from the understanding of medicine to how someone trained to become a doctor, to how patients were treated.

Most physicians in colonial North America were trained through apprenticeships, not by attending medical school. There just were not many medical schools available in North America. Medical schools thrived in countries throughout Europe such as in Scotland and France, but the first medical schools in the Colonies were not established until 1767 with King’s College in New York and 1768 with the Philadelphia College of Medicine. More commonly, apprentices paid an experienced physician to observe and work under their tutelage for an average of seven years to obtain a certificate of proficiency. This certificate granted the bearer the same practicing privileges as a medical school degree. Some historians suggest that this system of education was more effective than attending medical school for most of the coursework at universities were then focused on lectures instead of clinicals. As a part of being a physician, not only did one record and treat the ailments of his patients, he stocked his own pharmaceutical and medical supplies and decided upon the fees charged patients for his care. Some accepted services in-kind rather than payments of money, especially in rural areas. Ebenezer Roy, who practiced west of Boston in the mid-1700s, accepted “salt pork, rye, and labor in exchange for medical care”. Daniel Pierce, a physician in Kittery, Maine, logged payments in the form of “a linen handkerchief, brown sugar, butter, and a bushel of ‘Ingeon meal’” for medical services in his logs.

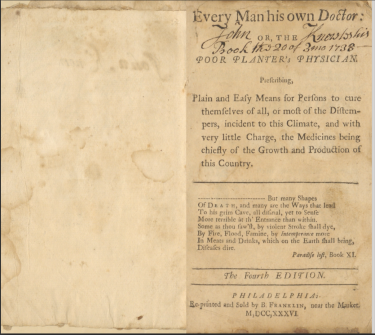

Many colonists lived in rural areas that lacked easy access to a physician. Mothers and wives often took up the role of healer for families and communities, bringing in physicians for more serious ailments. While women were typically responsible for medical care within the family, they rarely received a formal medical education. Instead, they used herbal remedies passed down through generations as well as guidebooks that were published in throughout the 1700s. One such book was Every Man His Own Doctor: OR, The Poor Planter’s Physician which contained “plain and easy means for persons to cure themselves of all, or most of the distempers, incident to this climate, and with very little charge, the medicines being chiefly of the growth and production of this country”. Using information contained in various editions of this book, many women created herbal medicines thought to cure ailments. Herbs like lavender, rosemary, wormwood, sage, foxglove, mint, and more found in gardens helped cure ailments from headaches, dropsy (swelling), to stomach pains. For example, the regimen listed in The Poor Planter’s Physician for fevers was to “drink freely of water gruel, orange whey, weak chamomile tea; or if his spirits be low, small wine-whey sharpened with the juice of lemon”.

The treatment might seem odd by today’s standards, but medical knowledge in the 18th century was not as advanced as it is today. It was illegal, in all but a few circumstances, to study human anatomy thereby limited the knowledge of the human body and how diseases affected it. Additionally, there was almost no knowledge of germ theory or sanitation and so there was little understanding of what caused diseases. Some diseases were thought to come from contaminated food or water, such as dysentery, typhoid, or cholera, instead of the true causes of bacteria or viruses. Other diseases such as malaria, yellow fever, or typhus were thought caused by “morbid” or noxious vapors when they are actually caused by microbes or parasites found in environments. Another common school of thought of what made people sick was known as the humorous theory. This perpetuated the idea that when someone was ill, it was because there was an imbalance of the four humors that balanced the human body. The four humors were blood, yellow bile, black bile, and phlegm and some of the best ways to rebalance these humors was through bleeding and purging through various teas, medicines, and medical procedures.

There were many diseases common in the 18th century which were thought to be caused by an imbalance of the humors. Ailments such as gout, smallpox, fever and even pneumonia that caused a fever created an imbalance of blood that needed to be corrected. Using lancets, leeches, or a new invention, a scarificator or a spring-loaded box with 12-16 lancets that delivered parallel cuts, physicians hoped to rebalance the humors by removing the excess blood that caused fever and sickness. Dr. Benjamin Rush, signer of the Declaration of Independence and member of the Continental Congress, was a prominent supporter of the humorous theory and the bleeding method. Rush reported in 1793 in treating Yellow Fever that “I have found bleeding to be useful, not only in cases where the pulse was full and quick, but where it was slow and tense. I have bled twice in many and in one acute case, four times with the happiest effect.” Unfortunately, the treatment did not always work for removing too much blood could make the patients weak and unable to recover. One of the most famous examples happened to George Washington, who in December 1799 contracted a sore throat. Over the course of his treatment, he was given mixtures of vinegar and sage tea, and bled. Over two days, more than thirty-two ounces of blood were removed from the former President, after which his condition worsened, and he passed away on December 14, 1799.

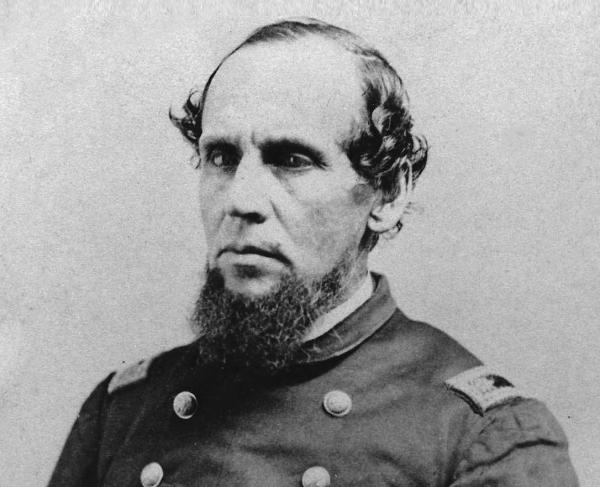

The American Revolution had an impact on medical science in the eighteenth century. Over the course of the Revolution, disease and infections were deadlier to soldiers than combat wounds. An estimated 6,800 American soldiers were killed and 6,100 were wounded. 17,000 deaths were caused by disease. The most common wound soldiers experienced during the American Revolution were caused by musket balls. According to Dr. John Jones, who wrote the textbook for surgeons in the Continental Army, Plain Concise Practical Remarks on the Treatment of Wounds and Fractures, the proper treatment for a gun-shot wound was as follows:

The first intention, with regard to wounds made by a musket or pistol ball, is, if possible, is to extract the ball, or any other extraneous bodies lodged in the wound. The next object of attention is the hemorrhage, which must be restrained if possible, by tying up the vessel with a proper ligature…

In order to extract a musket ball, the surgeon first had to first find it using a probe or finger. Surgeons then removed the ball with a forceps. If it could not be removed, the lead ball was left within and the wound was cleaned and bandaged. If the wound caused catastrophic damage beyond repair, surgeons could amputate. All of this was done without the use of anesthesia to numb the pain for it was not yet invented. Instead, surgeons used alcohol, provided something patients to bite down on, or some soldiers passed out from the pain. Since there was little knowledge of germs or sanitation, almost all surgeons operated without gloves or cleaning their instruments, causing infections to spread rampantly throughout the wounded, almost just as quickly as disease.

Bringing soldiers together in close quarters with poor nutrition caused diseases such as dysentery, fever, and diarrhea to spread throughout the armies. Additionally, over the course of the Revolution, the colonies were in the midst of a smallpox epidemic from 1775-1782. While inoculations have been around for thousands of years, they were more commonly used by wealthy colonists and were not as readily available to the lower classes who quarantined instead. Inoculations were also dangerous since it involved spreading the virus from someone who was recovering from smallpox to the person receiving the inoculation. To perform an inoculation, a small cut was made in a smallpox sore, and a piece of thread was run through the cut. The thread was then strung through a similar cut made on a healthy person receiving the inoculation. The recipient would get sick, although not as severe, and after they recovered, they were immune to the disease. However, if the recipient was not properly quarantined while recovering, it could lead to an outbreak among the local community.

After several outbreaks among the Continental Army, General George Washington decided to inoculate all of the troops in February 1777. In a letter written to Dr. William Shippen Jr., Washington wrote:

Finding the Small pox to be spreading much and fearing that no precaution can prevent it from running through the whole of our Army, I have determined that the troops shall be inoculated. This Expedient may be attended with some inconveniences and some disadvantages, but yet I trust in its consequences will have the most happy effects.

Throughout the remainder of the war, through the use of inoculations and quarantine, large-scale effort to reduce the disease was enacted and was largely successful.

While eighteenth-century medicine is considered very dated to the standards of today, it was revolutionary for its time. Prominent figures in the medical field including Dr. Benjamin Rush and Dr. John Jones, as well as revolutionaries including Benjamin Franklin, Abigail Adams, and Thomas Jefferson, contributed to the advancement of medicine through their actions and discoveries. Benjamin Franklin experimented with several home remedies including diets and “cold air baths” and Abigail Adams inoculated her family at the beginning of a smallpox epidemic. As an advocate of healthy living through exercise and proper diet, Thomas Jefferson even realized the state of eighteenth-century medicine in that “while surgery is seated in the temple of the exact sciences, medicine has scarcely entered its threshold”. He was right, medical science would not enter its threshold until the nineteenth century where enormous changes from the beginning to the end of the century would foster in the modern medicine many of us are used to today.

Further Reading:

- Revolutionary Medicine: The Founding Fathers and Mothers in Sickness and in Health By: Jeanne E. Abrams

- Pox Americana: The Great Smallpox Epidemic of 1775-82 By: Elizabeth A. Fenn

- The Army Medical Department 1775-1818 By: Mary C. Gillett

- Plain Concise Practical Remarks, on the Treatment of Wounds and Fractures: To which is Added, an Appendix, on Camp and Military Hospitals; Principally Designed, for the Use of Young Military and Naval Surgeons, in North America By: John Jones

- Medicine and the American Revolution: How Diseases and Their Treatments Affected the Colonial Army By: Oscar Reiss, M.D.