Moments in Time: The Battle of Perryville - Part II

Late Afternoon, October 8, 1862

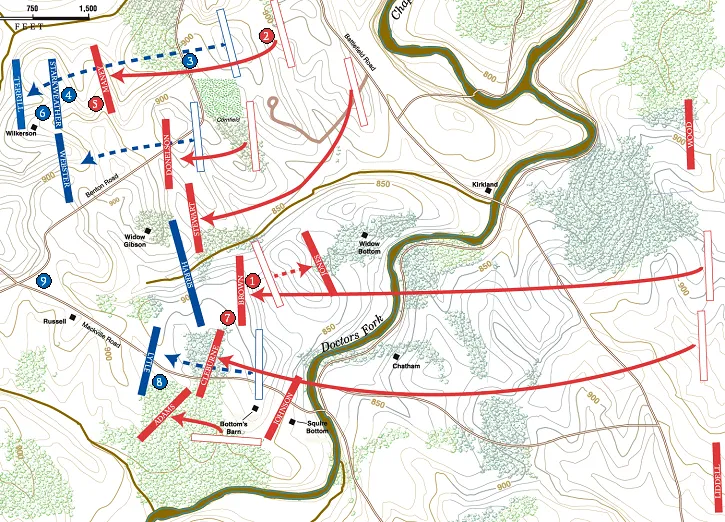

So far, both Union flanks had been bent back while the center struggled to hold. Ammunition was running low on both sides. At around 3:30 the second wave of Confederate soldiers stepped off: Patrick Cleburne’s brigade in the south, John Calvin Brown’s in the center, and A.P. Stewart in north. The worn-out men along the Federal line were in for a long fight.

1. “Colonel, I am not going to quit for that.”—Young soldier, 3rd Florida

Brown’s Floridians and Mississippians rushed forward to recharge the attack in the center, passing through the haggard survivors of Jones’s brigade. As they moved over the ridge these reinforcements met a new barrage of bullets from the stubborn Union defenders and halted to return fire. For thirty minutes waves of musketry crashed into the valley. One young soldier was shot in the leg but refused to leave the field until he was wounded again. Both sides hung on desperately even as sections of the firing line began to flicker out, cartridge boxes empty.

2. “Our only chance was to take those guns.”—Captain Thomas Malone, aide-de-camp

Losing valuable men every second, General Maney decided to take Open Knob with the bayonet. With a wild yell, his men scaled or tore down the fence and charged towards the blazing crest. The Union firepower overwhelmed the first attempt, forcing the Confederates to dive for the limited cover provided by the bodies of the 123rd Illinois. After a brief exchange the grey line rose again and surged onward. Unable to turn back the attackers with close-range volleys, the northern soldiers fled down the western slope of the hill. After an hour of heavy fighting, the men of Maney’s brigade had cracked the Union flank.

3. “Turning my head a little when sending a bullet home I saw but one man in sight—Charley Hitchcock, turned my head the other way, and saw but three men. I delivered that fire, and fell back to the regiment. We did not see Charley alive again.”—Private Lester Taylor, 105th Ohio

Some of the men of Terrill’s brigade bitterly contested the continuing southern advance as they fell back from Open Knob. However, facing superior numbers from lower, open ground, soldiers like Lester Taylor were in an untenable position. The retreat continued until the men were frantically pushing their way through the lines of Colonel John Starkweather. Starkweather’s inexperienced troops watched uneasily as the tops of Maney’s battle flags, barely visible over the tall corn, began to converge on their position.

4. “Boys be ready! They are coming!”—Sergeant John Otto, 21st Wisconsin

John Otto, a Prussian veteran, met the Confederate assault in Starkweather’s first line. The firing opened with the opposing forces no more than forty yards from each other, close enough that one Southerner was impaled by a ramrod fired by a Union soldier who was too afraid to finish loading his musket. Determined volleys from Otto and his comrades staggered the Tennesseans. The Federals took advantage of the brief pause to hastily draw back to the ridge behind them. Finding a group of four cannons abandoned at the crest, Otto gathered up a handful of men to man the pieces. Seconds after they finished loading and aiming, the Confederates were upon them.

5. “We killed almost every one in the first line, and were soon charging over the second, when right in our immediate front was their third and main line of battle from which four Napoleon guns poured their deadly fire. We did not recoil, but our line was fairly hurled back by the leaden hail that was poured into our very faces. Eight color-bearers were killed at one discharge of their cannon….It was death to retreat now to either side. The guns were discharged so rapidly that it seemed the earth itself was in a volcanic uproar. The iron storm passed through our ranks, mangling and tearing men to pieces. The very air seemed full of stifling smoke and fire which seemed the very pit of hell, peopled by contending demons.”—Private Sam Watkins, 1st Tennessee

Sam Watkins experienced the deadly effect of Otto’s quick thinking. His regiment’s flag was a dark navy blue color, leading some of the nearby Federals to mistake it for a black flag of “no mercy.” Recovering from the first bloody salvo, the Tennessee line surged forward to silence the Union guns at close quarters. The ridge and its slopes became engulfed in a maelstrom of savage hand-to-hand fighting and point-blank volleys in which many of the northern troops believed that surrender would mean execution. The untested recruits held their ground against the Confederate shock troops for nearly an hour but, after a brave and desperate struggle, A.P. Stewart’s brigade joined Maney in the melee and forced the Federals off of the hill.

6. “The agonizing cry of the wounded and pitiful heart-rending moan of the one that caused it will never be eradicated from my memory.”—Private Evan Davis, 21st Wisconsin

The Union men fled through a narrow valley and rallied on the next ridge. William Terrill was carried to the rear calling for his wife, a jagged shell fragment in his chest pulling his life away. Through the chaos the Federals tried to reform and reload. Evan Davis saw one man botch the loading process and accidentally shoot one of his friends. There was not much time to grieve. Reinforced by Stewart’s fresh troops, Maney’s ragged line continued to press forward up the steep slope. The Union men inflicted brutal casualties from behind a stone wall at the crest. The southerners charged four times and were repulsed with each attempt. Exhausted and decimated, Maney and Stewart pulled their men back. Out of the 9,742 Union and Confederate soldiers engaged in the northern sector, 2,773 became casualties. More than one in every five men had been shot.

7. “A young fellow, almost a boy, tried to shout. His excitement was so great that he only brought out a squeak. The effect was electric. The shout commencing on the left swelled along the line until it became a great roar.”—Colonel William Miller, 1st Florida

Colonel William Miller came into the great and sudden responsibility of brigade command after General Brown was put out of action by a shot in the thigh. He rose to the occasion admirably. Distributing fresh ammunition to the brigade, he ordered them forward to test the Union center once more. The men advanced with a rising yell. The attack gathered momentum as it swept forward. Adams and Cleburne were on the left, Donelson and Stewart on the right, and Mark Lowrey, taking over from a wounded Sterling Wood, led his brigade directly to Miller’s support. The shock of this combined attack quickly forced the Union right flank back towards the Dixville Crossroads, the spectacle alone usually being enough to move the line.

8. “I can do no more, let me die here.”—Colonel William Lytle, commanding Lytle’s Brigade

Small groups of men tried to stand in the face of the oncoming Confederates. Colonel Lytle rallied the 10th Ohio and turned them to face the enemy. Before they had time to form a solid line, they were set upon by the three brigades of Brown, Adams, and Cleburne. Advancing to within fifty yards, the southern volleys ripped the regiment apart. Lytle went down with a bullet to the head. He begged a friend to leave him behind as the Ohioans fled. In fact, Lytle survived and was captured by the men of Adams’s brigade.

9. “Will that sun never go down!”—Brigadier General Lovell Rousseau, commanding 3rd Division

The battered Union men resolutely formed another line on the Russell House ridge, knowing that every moment could be their last. Adams and Cleburne swept towards the rise only to be turned back by a tremendous fusillade. The Confederates were exhausted and disorganized—Patrick Cleburne had just received his fourth wound in the past five weeks—but if they could capture the Dixville Crossroads then their opponents would be cut off from the reinforcements that were beginning to arrive from the south. Above, the sky was beginning to burn into dusk.

Moments in Time at Perryville: Introduction | Part II | Part III