Moments in Time: The Battle of Second Manassas - The Battle of Brawner's Farm

August 28, 1862

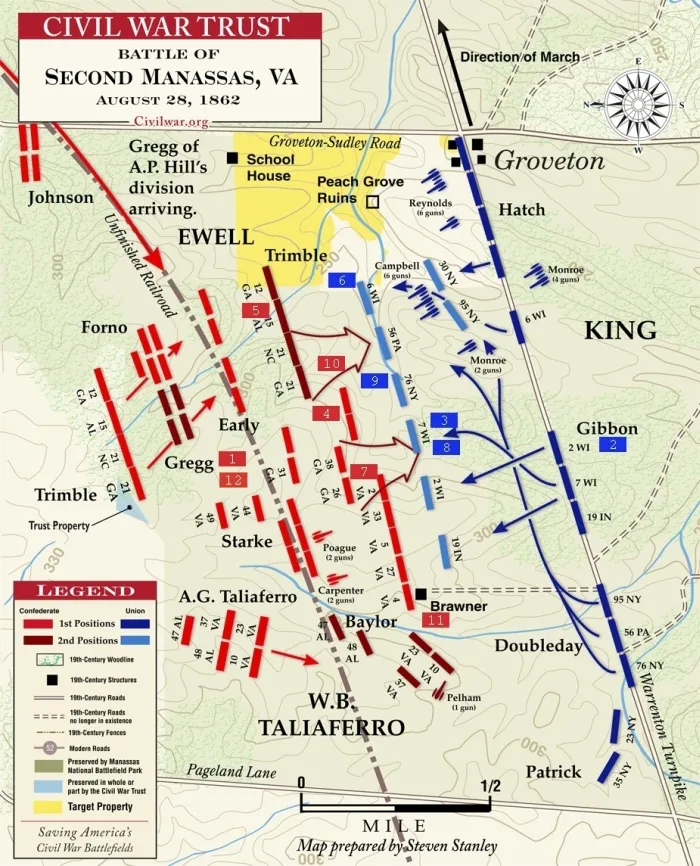

After three days of marching in the Union rear, wreaking havoc on supply depots at Bristoe Station and Manassas Junction, Stonewall Jackson’s men finally reached their destination on the morning of August 28, 1862. They were on the Bull Run battlefield, the site of the first major battle of the war a little over one year earlier. He had picked a position along an unfinished railroad excavation, a miles-long line of earth and stone piled as high as eight feet off the ground, surrounded by the treacherous Groveton Woods. Here was a magnificent spot for defense, if only Union general John Pope could be persuaded to attack.

1. “Bring out your men, gentlemen.” – Major General Thomas J. “Stonewall” Jackson (CSA)

Stonewall Jackson’s men watched nervously as their commander buckled a sword to his side and rode out alone. They could see the dust rising in great clouds from the road that snaked behind the farm fields to their south, and hear the steady tramp of a large body of Union soldiers marching towards the village of Groveton. Jackson galloped to within musket range of the column and deliberately took stock the ground his men would have to traverse for an assault. Evidently satisfied, he turned back towards his line several minutes later. “Here he comes, by God!” one his men shouted. They recognized the light in their leader’s clear blue eyes. Upon his return, Jackson quietly issued the order that began the second battle of Manassas.

2. “I was struck by the fact that the horses presented their flanks to view. My experience as an artillery officer told me at once what this meant; guns coming into battery!” – Brigadier General John Gibbon (USA)

Riding at the head of his brigade, John Gibbon’s eyes widened when he saw George Wooding’s Danville Artillery move into a firing line half a mile north of the Warrenton Turnpike. He wheeled and galloped back down the road, shouting orders to his men. White smoke began to rise from the ridgeline to the north as they halted and formed lines, loading their muskets and grimly watching thousands of Confederate veterans stream out of the opposite tree line. Showers of dirt flew into the air and fence rails shattered as shrapnel began to rain down over their heads.

3. “Just as I had faced about, there was a ball struck me in back of head and as it appeared to me, I spun around on my heels like a boy’s top and fell with my heels in the air and spun around again for a few seconds. Come too, roll over on to my knees, crawled off to the rear a few rods, got up, walked till come to little gutter in small hollow, laid down to rest but the balls fell around like hail striking very close so that wouldn’t do.” – William Ray, 7th Wisconsin (USA)

Gibbon's brigade moved out to challenge the onrushing Confederates. While crashing through a dense woodlot the left and right wings of his regiment moved too far ahead. William Ray was turning to scramble back to his lines when Georgians from Lawton’s brigade fired a volley into the trees. There would be more than two thousand similar stories by the end of the engagement.

4. “The comrade on my right fell, pierced through the head. Then the comrade on my left was shot through both arms. Then I was lifted from my feet by a ball hitting me high on the forehead.” –T.A. Cooper, 60th Georgia (CSA)

The 7th Wisconsin returned fire as T.A. Cooper and the 60th Georgia charged towards the center of the blue line that took shape as the Union soldiers spilled off of the road. Jackson himself rode a few yards behind the Georgians, urging them to keep advancing through the growing storm of lead.

5. “If I had held up an iron hat I could have caught it full of bullets in a short time.” – M.B. Houghton, 15th Alabama (CSA)

Brawner’s fields were mostly flat and open. When the two lines opened fire neither side had the sort of cover necessary to stop the .58 caliber minie balls that filled the air. In the words of Brigadier General William B. Taliaferro, “there was no maneuvering and very little tactics. It was a question of endurance.” By the end of the battle one in every three participants would be shot.

6. “During a few awful moments, I could see by the lurid light of the powder flashes, the whole of both lines. The two…were within…fifty yards of each other, and they were pouring musketry into each other as rapidly as men could load and shoot.” – Rufus Dawes, 6th Wisconsin (USA)

The sun began to set as the crash of musketry rose towards a crescendo. Jackson wanted a complete victory, which required him to drive his enemy from the field by nightfall. Galloping behind the lines and personally rallying groups of frightened men, he pressed his attack home.

7. “We held our fire until within a hundred yards of the enemy. We dropped behind a small rail fence and poured a heavy volley into them. After firing seven or eight rounds, we raised the rebel yell and charged.” -- G.F. Agee, 26th Georgia (CSA)

G.F. Agee and his comrades were ordered headlong into the teeth of the Union guns. In the gathering darkness and choking gun smoke it was impossible to see how many soldiers opposed them.

8. “There is nothing like it this side of the infernal region, and the peculiar corkscrew sensation that it sends down your backbone under the circumstances can never be told.” – Lyman Holford, 7th Wisconsin (USA)

Lyman Holford heard Agee’s rebel yell followed by the pounding footfalls of hundreds of men running directly at him. What exactly the rebel yell sounded like is one of the mysteries of the war. Noted historian Shelby Foote offered a compelling hypothesis: “something between a fox-hunter’s ‘yip’ and a banshee’s ‘squaw.’” In some cases the sound alone was enough to break a Union line. But Holford and the 7th Wisconsin had just been reinforced, and they held firm.

9. “No rebel of that column who escaped death will ever forget that volley. It seemed like one gun.” – A.P. Smith, 76th New York (USA)

Brigadier General Abner Doubleday had seen Stonewall Jackson scouting the Union column and knew trouble was on the way. The battle began while Doubleday’s men were still stretched out half a mile down the road. Galloping furiously, he drove them relentlessly towards the sound of guns. The 76th New York arrived in time to meet the final charge.

10. “The blazes from their guns seemed to pass through our ranks.” – B.F. Jones, 21st Georgia (CSA)

The final volleys were delivered with the opposing gun muzzles almost touching. The Confederates were finally hurled back; Jackson would not have his victory. Over half of the men of the 21st Georgia were killed or wounded in the firefight.

11. “It is now sundown. They are fighting on our right. Oh, to God it would stop.” – Joseph Kauffman, 10th Virginia (CSA)

Joseph Kauffman was a 22 year old farmer who had enlisted in the Confederate army for four months. His younger brother, Enoch, was in the 10th Virginia as well—they left four more siblings at home with their mother, Rebecca. Joseph was mortally wounded in the evening and died that night near a small stream. He made his last diary entry by the light of musket flashes as the Confederates withdrew to the woods concealing the railroad cut. Enoch was captured less than a year later and spent the rest of the war in a prison camp.

12. “The muscles were twitching convulsively and his eyes were all aglow. He gripped me by the shoulder till it hurt me, and in a savage, threatening manner, asked why I had left the boy. In a few seconds he recovered himself and walked off into the woods alone.” -- Hunter McGuire, surgeon (CSA)

Jackson’s nephew, William Preston, had joined his uncle’s army only three weeks before. The normally cold Jackson had taken a great liking to the young man, and news of his death near Brawner’s farm devastated him. There was little time to grieve. He had successfully drawn General Pope’s attention. Tomorrow his battered men would face the entire Union army.

Moments in Time at Second Manassas: Introduction | Part II | Part III | Part IV | Part V