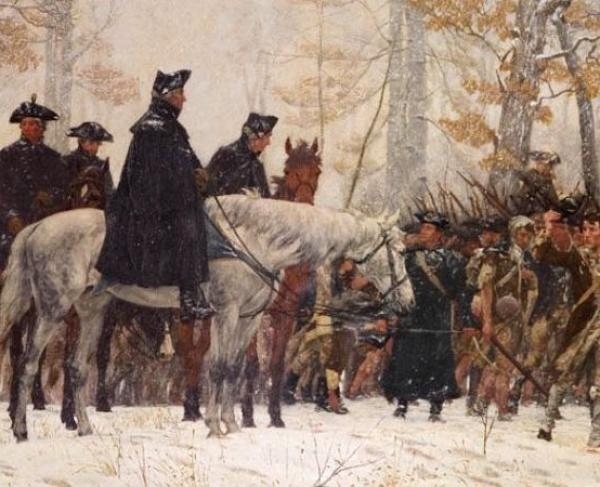

While the Continental Army’s encampment at Valley Forge in the winter of 1777-1778 is one of the most well-remembered events in American history, Washington’s winter encampment in Morristown, New Jersey in the winter of 1779-1780 marked another major milestone of the Revolutionary War.

The Continental Army camped at Morristown for a roughly six-month span from December 1, 1779, to June 8, 1780, though some troops and baggage remained behind until late in the month.

Located between New York and Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, Morristown, New Jersey provided a strategic location for Washington's army to make camp. Astride a network of roads, Morristown was the center for local farming to provide available foodstuffs and timber, which would later provide Washington’s army with necessary resources for a winter encampment. The Watchung Mountains also provided cover between the Americans and the British in New York City.

As Washington wrote to Congress, a camp near Morristown provided a location “compatible with our security which could also supply water and wood for covering and fuel.” This was not the first time Washington and his men camped in the Morristown area. Washington had selected Morristown for the Continental Army’s camp in the winter of 1776-1777, following the Patriot victories at Trenton and Princeton. During that winter, Washington went to work inoculating the army and many of the civilians living in and around the town in order to combat the threat of a smallpox epidemic.

While encamped at Morristown in 1779, Washington had his headquarters in the home of the late Colonel Jacob Ford, Jr. and his wife, Theodosia. During his time at the Ford Mansion, Washington chronicled the intense cold to which he and his troops were exposed, describing the winter as “intensely cold and freezing.” Martha Washington joined her husband at Morristown on New Year’s Eve. While the residence was larger than the Potts House in which Washington had his headquarters at Valley Forge several years before, the Washingtons’ shared the home with Mrs. Ford and her children, as well as both families’ servants, Washington’s aides de camp, and any visitors, making for a crowded space. It was from the Ford’s home that Washington worked to overcome the many challenges his army faced during the winter of 1779-1780.

After marching into Morristown in December of 1779, Washington’s troops settled in a few miles from town in an area called Jockey Hollow and the mostly wooded 1,400-acre farm that belonged to the Wick Family. Approximately 600 acres of wood from the Wick property would be utilized by the army that winter. The army also used land belonging to Peter Kemble, Joshua Gurein, and Dr. Leddel. Altogether, Washington’s men cut down over 2,000 acres of timber to construct a “log house city” of more than a thousand wooden log huts which accommodated about twelve men each. The site also included parade grounds and officers’ quarters, storehouses, and guardhouses. An estimated 10-12,000 soldiers camped at Morristown, although desertions and deaths reduced the number to only about 8,000. In total 96 men died, 1,062 deserted, 140 were captured, and 2,735 were discharged, whereas others were sent out on outpost duty. The end of three-year enlistments caused the greatest losses in the army. Lastly, the number at Morristown was reduced further in April, when the Maryland Line was ordered south and the New York Brigade left for the Mohawk Valley. and Washington claimed that as many as one-third of these troops were unfit for duty. With the harsh winter and the In spite of the factors working in the site’s favor, the conditions at Morristown, the harsh winter and shortages of food and clothing, would make the winter encampment of 1779-1780 the harshest winter of the war.

The extreme cold proved to be one of the army’s greatest trials during the winter at Morristown. Though Valley Forge is remembered for its harsh conditions, that winter in Morristown, Washington’s troops faced even bitterer cold than they had witnessed in Pennsylvania a few years before. Known as “the hard winter,” the season bridging the end of 1779 and early 1780 proved to be one of the coldest on record. Morristown received over 2o snowfalls during the Continental Army’s residence there, adding to the miserable conditions the troops faced in the wake of the shortages of food and supplies. In early January, there was a blizzard that lasted for two days, leaving 4 feet of snow in its wake. The temperature often remained below freezing, and snowdrifts piled up as soldiers struggled to keep warm with their scanty clothes and blankets. The challenges the freezing temperatures presented were only aggravated by the army’s serious lack of food and supplies. Shoes, shirts, and blankets were scarce, making conditions even more bleak as soldiers sought to fend off hunger and cold.

Shortages of food and other provisions also posed a constant challenge for the army at Morristown. Fresh meat was usually unavailable, and shortages of flour often made bread scarce. Washington noted that the soldiers sometimes went “5 or Six days together without bread, at other times as many days without meat, and once or twice two or three days without either.” According to some sources, soldiers were so desperate for food that they ate tree bark, leather from old shoes, or even dogs, a situation made worse by the fact that Morristown was located amidst numerous local farms. Despite their proximity to the farmland, however, drought had created shortages in the harvest seasons before, and farmers were often unwilling to give up their crops to feed soldiers. Farmers produced what they needed and if there was a surplus, traded to obtain other goods needed, thus making any excess crops valuable for the survival of the farmstead as well. The poor prices the Continentals offered for goods did not help either. The inclement weather added to the difficulty in transporting available supplies to the army. Community members’ reticence to offer their support to the Continental Army provided a constant source of frustration for the Commander-In-Chief. Though Washington was loathe to anger locals by allowing his troops to pillage their farms and fields, but in January 1780 he put a quota on every county in New Jersey to provide flour and meat. For all of February and early March, the army was well fed. But then food ran low again and New Jersey did not have any more food to spare. Food had to come from other states.

During the Revolution, the Continental Congress delegated the responsibility of supplying the army with materials and provisions to the thirteen states, which oftentimes resulted in empty commissaries. In a Circular Letter to the States, written on December 16, 1779, Washington recounted that “The situation of the Army with respect to supplies is beyond description alarming, it has been five or six Weeks past on half allowance, and we have not three days Bread or a third allowance on hand nor anywhere within reach.” Washington voiced his concerns regarding the shortages of food, supplies, and pay for the army, detailing the absence of adequate rations and funds for acquiring necessary provisions. According to Washington, the Army had “never experienced a like extremity at any period of the War,” signifying his distress over the conditions his troops faced. He expressed his fears that without relief, “the Army will infallibly disband in a fortnight.” Some historians suggest that this experience with the thirteen states during the Revolution influenced Washington’s as well as many other former soldiers, officers, and politicians to advocate for a more centralized Federal government during the Constitutional Conventions of the late 1780s.

Financial problems presented another source of difficulty for the Continental Army during the winter encampment at Morristown. Following a significant depreciation of Continental currency, the Continental Army struggled to find the funds to transport supplies, send messages, or even buy local provisions, whose sellers were hesitant to accept the Continental currency that frequently fluctuated in value. Many soldiers had not been paid for months, adding to their frustrations and increasing the risk that they would desert or choose not to continue supporting the war effort. Soldiers’ wages were often five to six months late, making it difficult to attract new recruits, secure reenlistments, or retain officers who were unable to support their families at home on minimal pay. This only added to Washington’s concerns about the fate of his army.

Worries about mutinies, desertion, and a British attack against the vulnerable Continental Army plagued Washington throughout the encampment at Morristown. In the spring, regiments from the Connecticut Line staged a mutiny in the camp, retaliating against the delayed wages and shortages of basic supplies, with the chief complaint being the shortage of beef. Though the small insurrection was quickly put down, it provided a stark reminder of the army’s dissatisfaction and demoralized state.

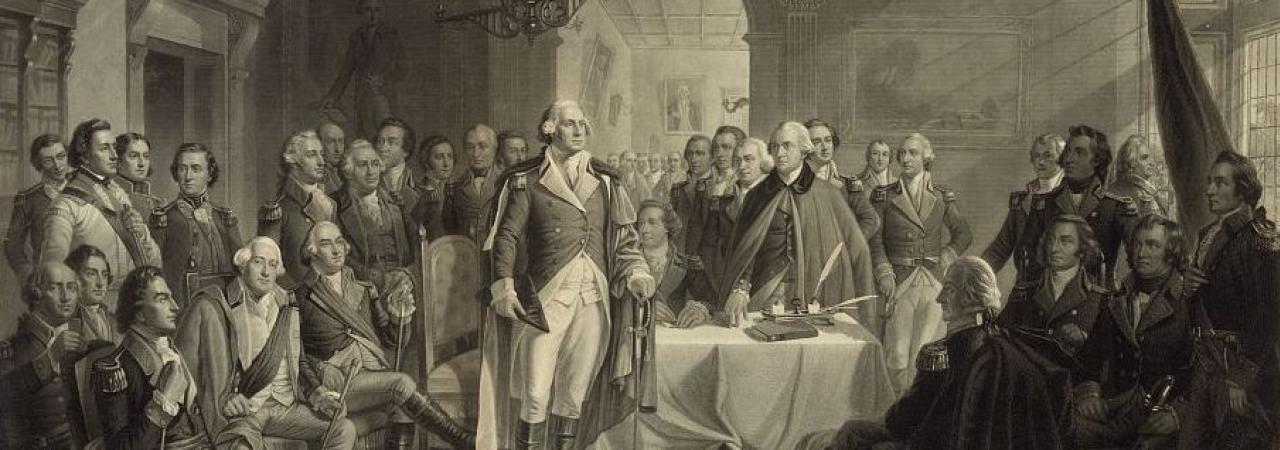

The Continental Army also saw several important personal and political developments while encamped at Morristown. On December 23, 1779, Benedict Arnold, who would later become the most notorious traitor of the American Revolution, was court-martialed in Morristown, where he was tried for abusing his power as an army officer for financial gain. In May of 1780, the Marquis de Lafayette returned to the United States and was reunited with Washington at the Morristown encampment. After spending the previous year persuading France’s king to support the American Revolution, the Marquis rejoined the Continental army bearing good news – the French would send a third fleet of ships; the first being sent to Newport, Rhode Island in 1778 and the second to Savannah, Georgia in 1779—across the Atlantic to assist the Patriot forces. The encampment at Morristown also proved significant for Washington’s right-hand man, Alexander Hamilton, who met Elizabeth Schuyler, his future wife, that winter. Besides finding love, Hamilton also wrote a paper suggesting improvements to the financial system of the United States, including the idea of a National Bank. Although not implemented at the time, these suggestions of 1780 became portions of the reforms he advocated for as Secretary of the Treasury in the 1790s.

Much like Valley Forge, the winter encampment at Morristown, New Jersey became an important symbol of patriotism and persistence in the American Revolution. In the most severe winter encampment of the war, weather-wise at least, Patriot forces held together, despite all the conditions that threatened to tear the army apart. In the winter of 1779-1780, the Continental Army’s perseverance and determination to overcome the challenges they faced prepared them for the campaigns that would eventually secure American Independence.