The Beggar's Opera. Painting by William Hogarth, circa 1728.

The eighteenth century in North America was a time of great change and growth. Population, industry, communication, and settled lands continued to grow and expand. The population in North America alone had grown to nearly 1.5 million people by the late 1750s, and the recent arrival of numerous immigrants from England, Ireland, Italy, and Scotland not only increased that number but also provided a labor force for the changing economic engines that drove many of the colonies in British North America. As the century pushed forward, many of the colonies moved away from their agrarian roots, relying on domestic industry to fill their material needs and deliver monetary capital. By mid-century, not only had there been tangible growth and expansion in many areas of life in North America but also, ideological ideas and philosophies for many changed as well, a growing desire for independence from the tyrannical motherland among them. All of these seemingly disparate transformations across British North America combined to produce an incredibly rich and vastly diverse musical landscape.

From the very beginning of the colonial era, as settlers stepped on to dry land in Jamestown, Virginia in 1607, excluding the spiritual musical heritage and religious traditions of the Indigenous population, the music that is found embedded in the colonies of the eighteenth century was based on the musical traditions of other cultures and peoples. These aural traditions came mostly from Great Britain, Europe, and through the arrival of slavery to the continent, Africa. The variety of musical styles and genres ranged from tribal drumming with its unique rhythms and call and response songs led by workers in the fields to classical forms such as the sonata, dances like the minuet, and comic operas. By the eighteenth century, these musical worlds had combined, producing new, unique harmonic and melodic sounds of their own. They had started closely aligned to the sound and words that had been brought to North American shores, but through the rote passage of these songs and pieces, a small melodic addition here, or different lyrics there distanced these songs and genres from what native countrymen across the Atlantic would have recognized. Further changing these musical traditions between the settlement of Jamestown and the colonies as we find them in the eighteenth century, were the many regional influences on music as westward expansion, growing settlements, and newly created regional identities became entrenched. Thus, the music of the eighteenth century in North American culture encompassed numerous styles, genres, use of instruments, regional elements, and many other varied influences, all of which made their mark on the music of this century.

Perhaps heard most by those living in North America was music sung and performed at church. Religion was an important component of the daily and weekly lives of those that lived in North America during this time period. Church music was also perhaps the most varied of all music during this era as many strong denominations spread across the settlements of the colonies during the century. In New England, parishioners of Congregationalist churches heard musical styles performed during services that ranged from complicated fugues, to anthems and psalms. As the end of the first quarter of the century drew nearer, churches in New England began to employ, in paid positions, music directors, then referred to as singing masters, to unwrap the seemingly mysterious language of written music for the parishioners, teaching them how to read music on their own. It was also during this time that many new compositions for the church were composed.

As noted earlier, regionalism played a role in the music of the church as well. Instruments and professional musicians did not grace many southern congregations. In fact, oftentimes there were more organs, often associated with church music, found in private homes across the south than in churches. Other examples of regional influences in music in the church can be found among the many German settlers in North Carolina and Pennsylvania. These Moravians, as musicologist Dr. David Hilebrand noted, “copied, performed, and even composed new chamber pieces that were far superior to the general level of musical accomplishment in the colonies.”

Another popular type of music at this time, hedonistic in the eyes of the church to be sure, was dance music. This genre of music was especially vast as were the dances that accompanied them, including musical styles such as jigs, country dances, reels, allemandes, minuets, and many others. Most often, these styles of music, all to support the dancing, were performed by a solo violinist, although there are examples of pieces requiring up to a quintet of musicians. Not only did dance music and their associated dances provide for hours of entertainment, but the music also served as a backdrop to a social gathering where many colonists could gather, discuss current events, network, and the like. The music, the dancing, the evening, it all quickly became a favorite genre and occasion for those living in the colonies during this time.

Those living in North America at this time also found music in another favorite form of entertainment - musical theater. Although the primary source material suggests little widespread theatrical performances in the colonies before the 1720s, just a decade later it was gaining popularity. The first significant English-speaking opera, with all of its musical trappings, was performed in Charleston, South Carolina. The musical genre took off. Between the 1730s and the beginning of the Revolutionary War, urban settings in the northern colonies and places of significant commerce and means in the southern colonies saw a boom in theatrical productions. Sadly, with the entrance of the colonies into war, the Continental Congress determined the focus of the attention of those committed to the revolution’s ideologies should not be lured by distractions such as theater. Although traveling theatrical groups, including musicians, began again after 1784, it took most of the 1790s to see the musical genre flourish once again.

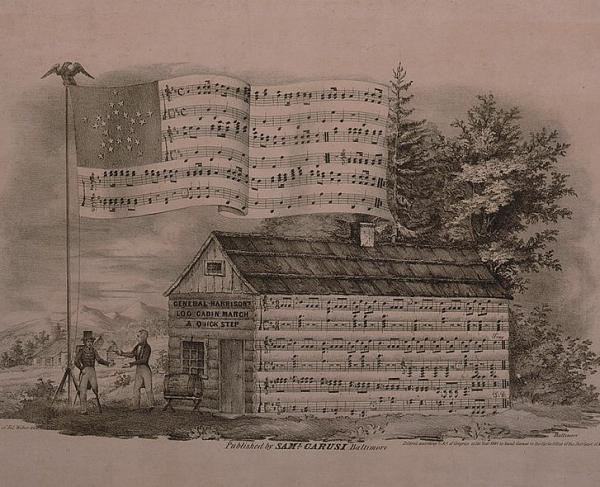

Through it all, even after the establishment of the United States of America and the yoke of British rule gone, music of the theater, opera was still based on the British tradition, and continued to be so for decades to come. The most popular that was performed in the colonies were ballad operas. This type of opera was a British reaction to the more formal, stiff, and musically sophisticated Italian operas of the day. Ballad operas were composed of folk melodies and songs, and coupled together with spoken dialogue, told a comedic story to the audience. It was opera for the people, not the bourgeois class who could afford to attend and understand the language of an Italian opera. Perhaps the most famous ballad opera to import itself from the London stage was The Beggar’s Opera, a three-act work that included themes of violence, stealing, and laziness. First premiered in London in 1728, the smash success debuted in the colonies sometime in the 1750s.

Between the formality of music in church, structured dance music, and full musical productions of theater, folk music became yet another staple of culture in North America during this century. For many, it was songs performed by one or a few musicians at taverns or gatherings with more personal meanings that were heard the most by the average colonists of the era. Colonists often wrote and performed music that spoke to their daily lives. Folk music was also a way for colonists to keep their cultural traditions and customs alive and thriving in the new world. But, as frustrations grew between the colonies and the Crown, often these intimate performances included music that spoke to their audience’s grievances. Songs about the lack of representation in Parliament and mocking English leaders became quite popular in the colonies. An example of this type of colonial music can be found in the song “A Taxing We Will Go.” The imposition of the 1765 Stamp Act outraged the colonists, many arguing the injustice of being taxed in the colonies without representation in Parliament in London. The lyrics of this song specifically focused on the topic at hand, noting “The power supreme of Parliament our purpose did asist, and taxing laws abroad were sent, which the rebels do resist….”

Colonists were also exposed to a completely new listening experience performed by symphonic orchestras in large, grandiose concert halls. New York, Boston, and Philadelphia were just a few large cities among the northern colonies that offered a thriving musical experience for citizens. Although symphonies had thrived in England, Germany, Italy, and many other places in Europe for a century, the colonies would not have an opportunity to hear this genre of music for most of the eighteenth century. By the second half of the century, however, concert halls were being constructed and welcoming orchestras and audiences. Now, colonists living within easy traveling distances of these large cities could take in famous works by Baroque composers Johann Sebastian Bach, Antonio Vivaldi, and George Frideric Handel. Additionally, they would have the opportunity to hear newer works by emerging composers such as Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart, Ludwig van Beethoven, and Joseph Haydn. Yet, as the Classical Era of Western art music expanded across Europe and England to larger audiences of more social classes, accessibility to these popular musical traditions were still far less to those living in the British North American colonies due in large part to the small growth of large concert halls in the northern colonies. Concert halls that could enable a platform for these master composers’ works did not become a stronger part of American musical culture until the beginning of the nineteenth century.

As war later settled across the colonies, the role of music in the daily lives of soldiers and civilians only increased. Music was heard in several ways by both officers and men of the Continental and British armies, all of which led to it embedding itself in the musical culture of the century. All military music was not the same, however. Soldiers, men in the ranks, were almost continually hearing “field music,” musical calls that acted as commands while on the march, in camp, or on the battlefield. Musicians could easily play over the loud sounds of battle providing troops with cadence marching and even tactical signaling. Such instruments that could rise above the din of battle were the fife and drum. Of the two, drummers were one of the most important musical positions that could be held within a military band or unit. After enlistment, drummers were required to learn and memorize numerous rudiments or beats to utilize throughout each day in camp, while on the march, and in battle. One of the most well-known rudiments from the American Revolution is “Reveille.” It was to be played each day at daybreak to alert the soldiers to “rise and comb his hair and clean his hands and face and be ready for the duties of the day” as well as the cessation of challenging by the guard.

Another form of military music was performed by a “Band of Musick...professional musicians hired by officers to play contrapuntal music at parades, during meals, and for dancing.” Men in the ranks would have had less exposure to these musical events, conversely, though, civilians attending these events did. A popular song of the era, “Yankee Doodle,” was originally sung by British military officers as a way to mock the sad state of the colonists and their army. Surely “Band[s] of Musik” performed this song of mockery for officers and well-to-do loyalist citizens at those social military gatherings. To the surprise of many British officers and enlisted men though, General George Washington’s men turned the derogatory implications of this song around and used it as a song of defiance and pride. Thus, “Yankee Doodle” rose to be a song of not just colonial, but national acclaim.

From beginning to end, the eighteenth century in North America can be seen as a period of immense change. An influx in immigration, a rapidly growing population, a shift in gross domestic products, and philosophical and ideological division with the laws and politics of England within the colonies are only some of the many changes witnessed by those who lived through this turbulent time. Music during this period was no exception when it came to change. In Western art music, the Baroque Era had ended and given way to the Classical Era. Musical theater had arrived in the colonies, adding a new genre of music and entertainment to the colonists. Songs and music about the colonists’ daily lives gave way to reflect their growing frustrations and mood towards England, independence, and war. With that change came new musical soundscapes as colonists entered the army and British armies occupied and moved through vast sections of the colonies themselves. Military music and musicians thus entered the colonial musical scene. The confluence of all this social and cultural change spawned a new, rich, and diverse musical landscape that continued to solidify as the war gave birth to a new nation, music that has remained embedded in the history of eighteenth-century culture in North America.

Further Reading

- Early American Music By: David K. Hildebrand

- Military Music of the American Revolution By: Raoul F. Camus