Sunrise at the Peach Orchard at Gettysburg National Military Park, Gettysburg, Pa.

The fluffy blossoms that adorn fruit trees are sure sign of spring, drawing tourists and family photoshoots. But during military engagements, orchards were far more than scenic and photogenic spots. Since most self-sustaining 18th- and 19th-century farms had orchards, and most Revolutionary War and Civil War battles were fought in agricultural areas, it should come as no great surprise that troops sometimes ended up locked in bloody combat in groves of peach or apple trees.

Today, remnants of historic orchards remain within many battlefield parks. At some battlefields, orchards have been replanted not so much for the fruit but for better historic context and battlefield interpretation. These efforts, however, have had mixed results. Orchards, it seems, are high-maintenance projects that are vulnerable to pests, wildlife and cold weather, especially young trees. Park rangers have discovered that successful orchards require adequate maintenance budgets and a corps of dedicated volunteers.

Learn more about these historic orchards and the exacting work done to care for them from the National Park Service.

The Most Famous Fruit: Gettysburg’s Peach Orchard

Forty four orchards existed during the Civil War on what is now Gettysburg National Military Park, but only one, the Sherfy Peach Orchard, or simply The Peach Orchard, became iconic because of the battle.

Before the battle, the Sherfy peach orchard was well known locally for its fresh, dried and canned peaches. It was also on high ground along Emmitsburg Road and during the second day of the battle, which prompted Union Gen. Dan Sickles to impulsively moved his corps out ahead of the rest of the Union line and occupy it. The move created a bulge in the Union line that the Confederates attacked from both sides, leading to bloody carnage among the peach trees. The Confederates eventually took the position.

The Sherfy farm was devastated in the battle. The house was ransacked and damaged by artillery shells. The barn burned to the ground and within the fire-gutted ruins were the remains of wounded soldiers who had sought refuge there but were too badly wounded to escape the flames. The orchard itself was damaged, but 114 trees survived, allowing the Sherfys to continue harvesting and selling fruit. Ultimately, as battlefield tourism began to thrive, the family business was enhanced by its connection to the battle.

Eventually, the orchard disappeared, but in 2008 the National Park Service created a new one with 72 peach trees provided by the Gettysburg Foundation. The park service has also been restoring other historic Gettysburg battlefield orchards. Since 2000, the park service has planted 2,869 apple trees on 109 acres at 35 historic orchard sites within the park.

The Apple Orchard at Gen. Lee’s Headquarters

The American Battlefield Trust has worked to restore another historic Gettysburg orchard—this one at Gen. Robert E. Lee’s Headquarters. Unveiled on Arbor Day in 2017, the orchard reflects the agricultural landscape that surrounded Seminary Ridge during the battle. In 1863, this site was flanked by farmland and fruit trees, a familiar setting for both the local population and the soldiers who marched and fought there.

By replanting apple trees at Lee’s Headquarters, the Trust aimed to do more than beautify the property. Like the Sherfy Peach Orchard restoration, this project deepens the interpretive experience by connecting visitors to the wartime environment—one where combat frequently unfolded amid barns, fields, and fruit groves.

The other now-eponymous Peach Orchard at Shiloh

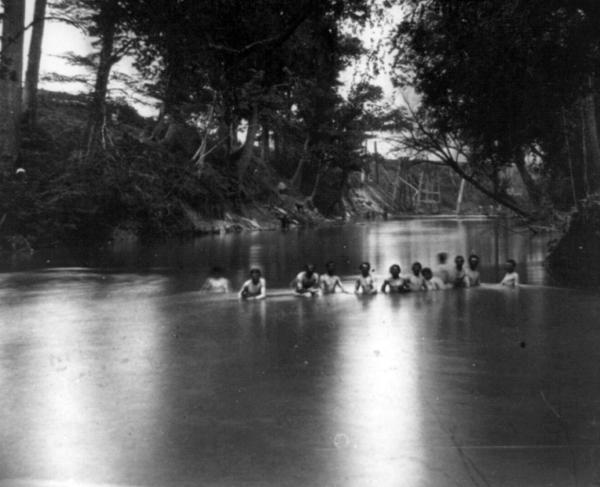

Sarah Bell’s peach trees were in full bloom at Pittsburg Landing on April 6, 1862, when her orchard became the epicenter of furious Confederate attacks in the first day of the Battle of Shiloh. Soldiers remembered that peach blossoms fell like snow as the minie balls ripped through the trees.

For most of its existence, the site of The Peach Orchard at Shiloh National Military Park has been an open field. Some years ago, the National Park Service began planting young peach trees in an effort to restore the orchard, but they struggled to survive cold weather and wildlife depredations. Trying a different approach, the park service in 2021 planted dozens of three-year-old June Gold peach trees. But these have struggled, too, and as of 2025 only a few survive.

The Piper Farm Orchard at Antietam

Small orchards dotted the farms of Samuel and Joseph Poffenberger, William Roulette, Samuel Mumma, Joseph Sherrick, Henry Rohrbach and John Otto, but Henry Piper’s apple trees were the only commercial orchard in the area of Sharpsburg, Md. These trees just south of the Sunken Road were devastated by fighting, with a Union soldier recalled “how the twigs and branches of the apple trees were being cut off by musket balls and were dropping in a shower.”

By the end of the 19th century, there were no more apple trees on the Piper Farm. But beginning in 2002, the park service began planting period appropriate varietals of apple tree. Twenty acres of trees have been planted, but deer and disease have taken their toll. Today’s orchard at the Piper Farm is smaller than the wartime orchard and while there are significant gaps in the rows, there also are healthy trees that produce new and old varieties of apples every season.

Orchards at Minute Man National Historical Park

At Minute Man National Historical Park, where the first shots of the American Revolution were fired 250 years ago last week, at least four historic orchards have been identified. At Fiske Hill at the park’s eastern end, the park service has plated three areas with crabapple trees in grid formations to resemble orchards, although many trees were reported in poor condition.

Near the historic Hartwell Tavern, the historic cider orchard was recreated, although only seven trees were planted, too few to contribute to the historic character of the site. Nearby mature fruit trees may be remnants of historic orchards. Remnant orchard trees also exist around the Noah Brooks Tavern and at several locations near the North Bridge at Concord.

The Peach Orchard at Pea Ridge

The Battle of Pea Ridge in northwest Arkansas was the largest Civil War battle west of the Mississippi. During the battle on March 7-8, 1862, fighting raged at the Ford Farm and its peach orchard as well as Elkhorn Tavern, with a nearby apple orchard.

In 2008, volunteers and NPS staff planted 46 peach trees intended to replicate the historic appearance of the Ford Farm. A few trees have grown nicely, but many have struggled. The park service has assessed the condition of the orchard as “poor to fair” and reports that it has not thrived for unknown reasons.

The Borden Apple Orchard at Prairie Grove

The Borden Apple Orchard on the Prairie Grove Battlefield was what one witness called a “perfect slaughter pen” during the Battle of Prairie Grove on Dec. 7, 1862, as Union forces triumphed in the last major Civil War engagement in northwest Arkansas. The battle inflicted more than 2,500 casualties, with the heaviest losses in this orchard. With many mature trees, a variety of apples and a dedicated corps of volunteers, the Borden orchard today is one of the best examples of a historic orchard on one of the Civil War’s best-preserved battlefields.

The Brawner Farm Apple Orchard

The park service has struggled in its efforts to replant apple trees on the Brawner Farm at the Manassas National Battlefield Park. The farm had an apple orchard that was the source of one anecdote from the Battle of Second Manassas. It is said that during the battle, Union Gen. Irvin McDowell spread out his maps under the branches of the apple trees at the farm and ate “apples by the basket” while plotting his next move.

The Wick Orchard at Morristown National Historical Park

Morristown National Historical Park, the nation’s first national historical park, is home to four significant historic sites of the American Revolution, including the Continental Army winter encampments of 1777 and 1779-1780.

After the park was established in 1933, the Wick Farm’s orchard was reestablished in its original location. Today, the orchard consists of 250 apple trees of varying age spread in a grid pattern over 10 acres.