Sam Davis

“I have got to die to morrow morning — to be hung by the federals,” wrote young Sam Davis on November 26, 1863. Many soldiers penned farewell letters during the Civil War—some when ill or mortally wounded, others with a heavy premonition of death in the next fight. Comparatively, few soldiers had to write to loved ones on the eve of their execution.

Davis’s brief, tragic letter recounts that he had been captured by Union soldiers who believed he was a spy and that he had been sentenced to hang. He asked his parents to not grieve too much for him and seemed to have somewhat accepted his fate. What were the circumstances that led to the writing of this letter? How has war memory treated Sam Davis?

Born on October 6, 1842, Samuel Davis grew up near Smyna, Tennessee, about twenty miles southeast of Nashville. When he was nineteen, he left his family’s farm and enrolled at Western Military Institute at Nashville. When the Civil War began in 1861, Davis enlisted with other Confederate volunteers and briefly served in the mountain region of western Virginia with the 1st Tennessee Infantry.

In the autumn of 1862, he joined a cavalry company called “Coleman’s Scouts,” which operated in south-central Tennessee, collecting information about troops and logistics around Nashville, Franklin, Murfreesboro, and Columbia. The scouts usually wore Confederate uniforms, but Union troops considered them spies.

Union General Grenville Dodge took a stand against the Scouts in the autumn of 1863 and ordered his soldiers to find and destroy the operators. At that same time, Davis and five other Scouts hovered around Dodge’s division and collected information.

Near Pulaski, Tennessee, Davis agreed to carry maps and details of the Nashville fortifications, a report of the Union army in the state, and a letter for Confederate General Braxton Bragg with information about Union troops. The following day—November 20, 1863—Union soldiers captured Davis and took him to General Dodge. The Union officers charged Davis with spying and carrying mail to rebels. Davis pled not guilty to the charge of espionage but accepted the charge for carrying papers. He was sent to trial by court-martial, and the presiding Union officers declared he was guilty on both charges. They sentenced Davis to hang.

General Dodge offered to grant leniency and freedom if Davis agreed to share the name of his contact who had given him the papers. Davis refused and declared: “I know that I will have to die, but I will not tell where I got the information, and there is no power on earth that can make me tell. You are doing your duty as a soldier, and I am doing mine. If I have to die, I do so feeling that I am doing my duty to God and my country.” With reluctant resignation, Davis wrote a final letter to his parents on the evening before his execution.

He described the experience of writing the letter as “painful” as he briefly communicated details of his fate and asked his family to remember him but not to grieve too much. Several times he signed the letter as though finished, but then continued to add more messages of love to his parents and siblings, along with a final note to his father regarding his personal effects and how to find his body after the execution. At the very end of the page, he added, “Hope something may turn up some day to let the officers that Guard me [know] that I am innocent.”

Both his last letter and reminiscences of his fellow prisoners suggest that the means of execution troubled Davis. He had expected to be shot as a soldier instead of hanged as a spy. Davis’s case was not abnormal. Both sides had already hanged suspected or charged spies, and in middle Tennessee, it was often done without much formality. Union troops in that area had a shaky grip on controlling the region and tended to make quick examples of spies that they caught with few trials or execution ceremonies. It is possible that General Dodge wanted to make an example of Davis or thought that the young man would give up the desired information at the last moment.

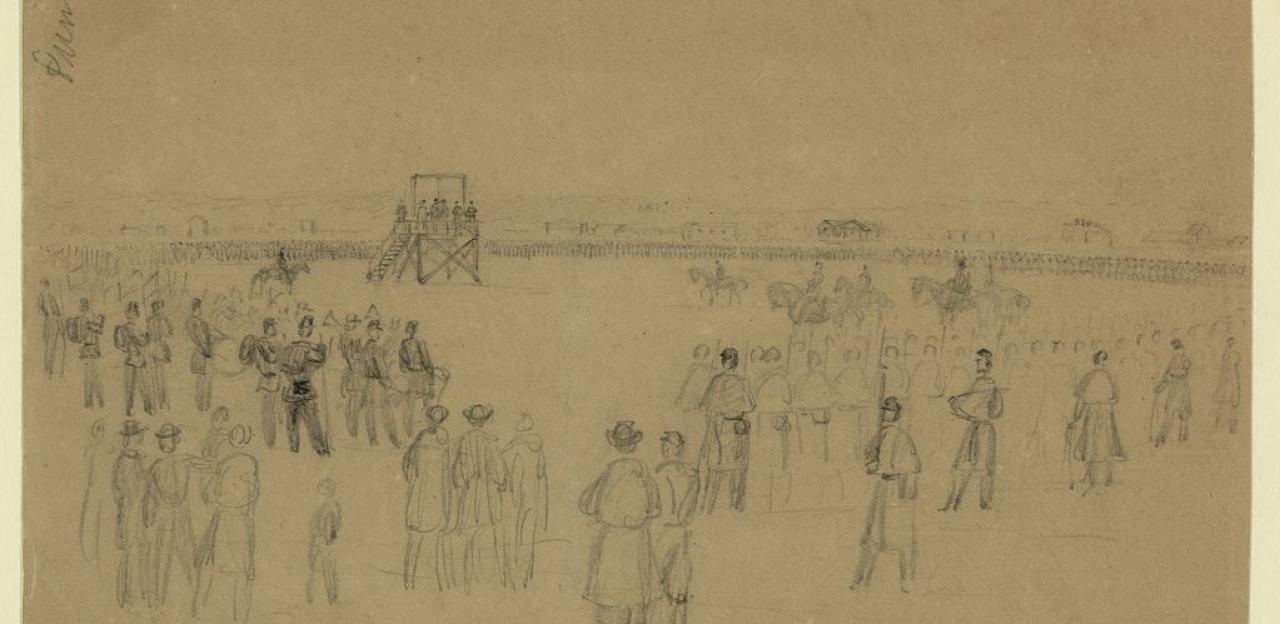

On November 27, 1863, Davis was taken from the military prison and to the gallows outside of town. There, he conversed with a Union officer for a few minutes and asked for the latest news from the battlefields. When told of the Union victory at Missionary Ridge, Davis remarked sadly, “The boys will have to fight the battles without me.” The officer expressed his own regret at Davis’s fate, but Davis continued to believe that each did their duty. Once again, General Dodge sent a message, asking Davis to reconsider. “If I had a thousand lives, I would lose them all here before I would betray my friends or the confidence of my informer,” Davis reportedly said, before climbing the scaffold. Sam Davis was executed, and his family was later allowed to receive his body which they buried at their farm.

In the post-war era, Davis became a loyal martyr figure in the Lost Cause and a local hero to many Tennesseans. Articles in the Confederate Veteran Magazine compared him to Nathan Hale of the Revolutionary War, and the Confederate veterans started a fund to create a memorial statue to honor Davis, who they called "The Boy Hero of the Confederacy." The Davis family home eventually became a museum, dedicated to preserving his story. Over time, questions have been raised about Sam Davis’s legacy which continues to be studied, appreciated, and questioned.

Davis died believing he had done his duty as a soldier. His final letter to his parents reflects the wish of this barely twenty-one-year-old young man caught in a war and in circumstances that had fatal consequences: “I wish I could see all of you once more, but I never will no more.”

Further Reading:

Edythe John Rucker Whitley, Sam Davis: Confederate Hero, (1947).