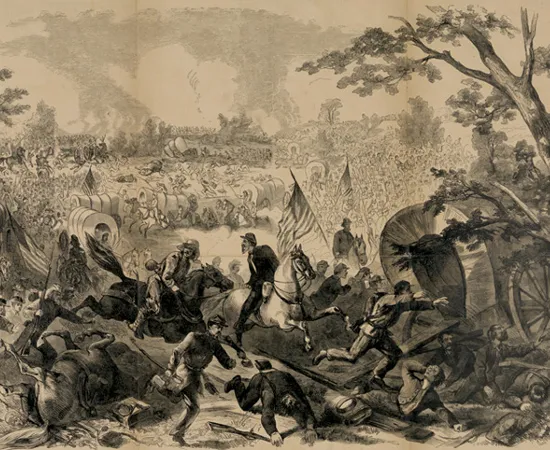

It is a popular, almost legendary, story that innumerable civilians armed with picnic baskets followed the Union Army out from Washington in July 1861 to watch what everyone thought would be the climactic battle of a short rebellion. These naïve citizens, the tale goes, then impeded the Union retreat, adding to the panic. Hollywood representations of Manassas have, unfortunately, perpetuated the notion that large numbers of civilians were actually under fire on the battlefield. Indeed, there were a few, like Gov. William Sprague of Rhode Island, who accompanied Burnside’s brigade and had two horses shot from under him on Matthews Hill. The majority of spectators, however, were well out of harm’s way on Centreville Heights, some five miles from the fighting.

In truth, many sightseers packed picnic baskets; but this was more a necessity than a frivolous pursuit on a Sunday afternoon. Centreville was a good 25 miles from Washington, a seven-hour carriage ride one way. The sightseers would need nourishment during their adventurous excursion and they could not rely on the hospitality of local Virginians, now citizens of a rival nation.

Near Centreville, Capt. John Tidball witnessed a “throng of sightseers” approach his battery. “They came in all manner of ways, some in stylish carriages, others in city hacks, and still others in buggies, on horseback and even on foot. Apparently everything in the shape of vehicles in and around Washington had been pressed into service for the occasion. It was Sunday and everybody seemed to have taken a general holiday; that is all the male population, for I saw none of the other sex there, except a few huckster women who had driven out in carts loaded with pies and other edibles. All manner of people were represented in this crowd, from the most grave and noble senators to hotel waiters.”

London Times correspondent William Howard Russell observed, “On the hill beside me there was a crowd of civilians on horseback, and in all sorts of vehicles, with a few of the fairer, if not gentler sex .... The spectators were all excited, and a lady with an opera glass who was near me was quite beside herself when an unusually heavy discharge roused the current of her blood —‘That is splendid, Oh my! Is not that first rate? I guess we will be in Richmond to-morrow.’ Irritated by constant appeals to borrow his glass, Russell decided to press forward after an officer rode up and exclaimed to the cheering crowd, “We have whipped them on all points.”

Most of the information filtering back from the battlefield was well over an hour old. All that could be seen of the battle from Centreville was gunsmoke rising above the distant treetops. Despite intensifying musketry and artillery fire in that direction, discontent with the view combined with encouraging news from the front emboldened a handful of politicians and others like Russell to venture westward in search of better vantage points beyond Cub Run. Among the notables in this crowd were senators Ben Wade of Ohio, Henry Wilson of Massachusetts, Jim Lane of Kansas, Lafayette Foster of Connecticut, congressmen Alfred Ely of New York and Elihu Washburne of Illinois, as well as soon-to-be-legendary photographer Mathew Brady.

These intrepid individuals found their way along the Warrenton Turnpike to a rise just beyond Mrs. Spindle’s house, a field hospital in rear of Brig. Gen. Daniel Tyler’s division. Upon arrival, they joined John Taylor of New Jersey, Judge Daniel McCook of Ohio and a half-dozen reporters who had been the only civilians in this vicinity until these mid-afternoon arrivals.

Ultimately the curiosity-seekers got caught in a stampede of retreating Union troops. McCook desperately raced back to Centreville with his son Charles, who had been mortally wounded while visiting and separated from his unit, as Confederate cavalry attempted to intercept the Union retreat. Photographer Mathew Brady was caught in the congestion at the Cub Run bridge. Congressman Washburne tried in vain to rally the panic-stricken mob of soldiers near Centreville, but most of the civilians joined, if not led, the flight back to Washington and escaped unharmed.

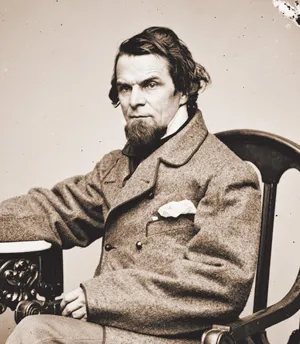

One notable exception was Congressman Ely who strayed too close to Bull Run and became a prisoner of the 8th South Carolina Infantry. Alone among all the politicians clamoring, “On to Richmond!,” Ely was successful; he spent the next five months residing at Libby Prison. Only one civilian was killed in the battle, the aged widow Judith Henry whose home was engulfed by the fighting.

Related Battles

2,896

1,982