The Yankee Van Pelt

By Ray Brown, Chief of Interpretation and Cultural Resources Management at Manassas; Hallowed Ground Magazine, Spring 2011

Scattered stones and shallow depressions amid a tree-shrouded summit mark the site of Abraham Van Pelt’s house on the Manassas Battlefield. Such nondescript remnants do little to convey to modern visitors the dramatic events that occurred on this ridge in July 1861, and the impact of the war on the Van Pelt family and their farm. Despite having witnessed the opening shots of the Battle of First Manassas, today the site today is often bypassed by hikers traversing the trail to and from the nearby Stone Bridge over Bull Run without a second thought.

The family of New Jersey native Abraham Van Pelt had lived on this 230-acre farm overlooking Bull Run for more than a decade when the nation erupted in civil war. With the advent of active campaigning in Virginia, the bucolic setting of the farm known as “Avon” turned strategic, as Confederate forces under Brig. Gen. P. G. T. Beauregard took defensive positions along Bull Run to fend off the Union offensive led by Brig. Gen. Irvin McDowell. The Van Pelts’ commanding ridge anchored the Confederate left, held by Col. Nathan Evans’s small brigade. The Warrenton Turnpike, which sliced through the farm on its way across Bull Run into adjoining Fairfax County, became a major avenue of approach for Federal troops.

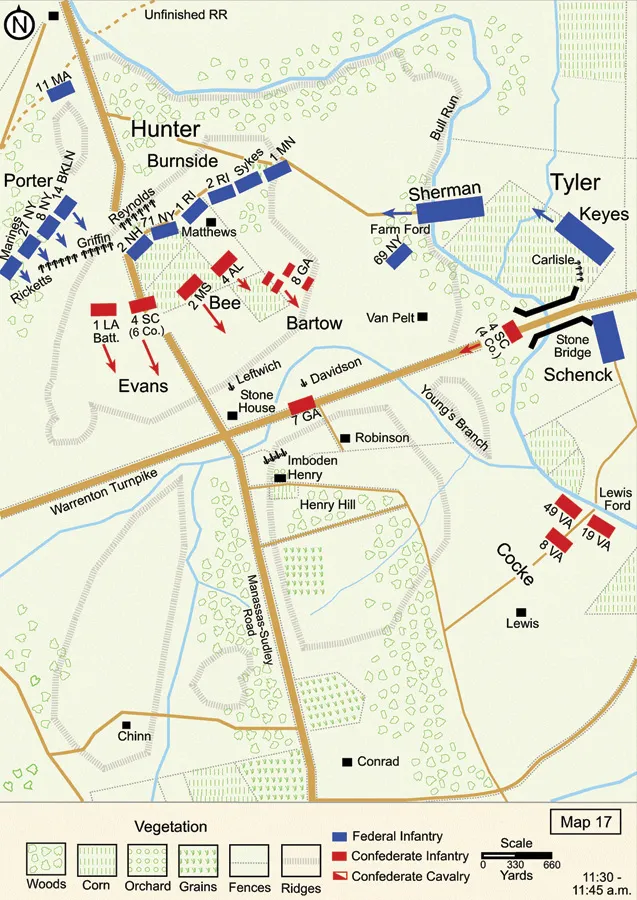

On the morning of July 21, Evans had deployed his forces wisely, taking advantage of the cover offered by the rolling terrain to conceal his meager numbers. In the pre-dawn hours, Union Brig. Gen. Daniel Tyler directed his division toward the Stone Bridge in a diversionary move, while a larger flanking column headed north to cross upstream. Near 6:00 a.m., Lt. Peter Hains ordered his gunners to fire their impressive but cumbersome 30-pounder Parrott rifle on the Van Pelts’ prominent white frame house, visible from more than a mile away. The opening salvo sent shells crashing onto the farmstead, with the second shot landing on the tent of Capt. E. P. Alexander’s signalmen, who were manning a signal station on the hill. Despite an oft-repeated claim, there is no contemporary evidence that the Confederates had erected an actual tower on Van Pelt Hill.

Skirmishing broke out along the stream banks and persisted through the early morning, but Evans held most of his men back until he could determine Federal intentions. The desultory musketry aroused his suspicions that the main blow would fall elsewhere. Near simultaneous messages, one from pickets posted upstream and the other from Capt. Alexander at a distant signal station on Wilcoxen’s Hill near Manassas Junction, alerted Evans to the Union movement upstream on Sudley Ford. The fiery Southerner stealthily marched the bulk of his command away, pausing first on the neighboring Carter plantation, Pittsylvania, and then heading to Matthews Hill to intercept the Union column marching south from the ford on the Sudley-Manassas Road.

In March 1862, Northern photographers George N. Barnard and James F. Gibson captured the scene of the opening engagement of First Manassas. A stereograph pair reveals the ruins of the Stone Bridge, destroyed by Confederates days earlier. On the ridge beyond, the Van Pelt house and farm buildings stand in stark relief in an otherwise desolate view.

The Van Pelts, Union loyalists in their adopted home, made fitful attempts to maintain their farm during the war. During the Second Battle of Manassas, Union troops commandeered the house and outbuildings for hospital purposes, and the Van Pelts temporarily moved to a tenement on a nearby farm. Facing repeated Confederate harassment, Abraham ultimately joined his wife, Jemima, in returning to New Jersey later in the war, while their son Augustus became a Union scout and daughter Elizabeth stayed behind to manage the farm. A married daughter, Evaline Cummings, had settled in Chesterfield County, Va. Later, Elizabeth filed a claim for damages to the estate of her father, who died in 1866. Much of the claim was disallowed, however, due in part to the uncertain allegiance of her mother and sister.

The Van Pelts’ house survived into the 20th century, but lay in ruins by the time the National Park Service acquired the site in 1936. The sparse remains today conceal the story of the first battle’s opening action and a Northern family caught amid the swirling events of war in a borderland.