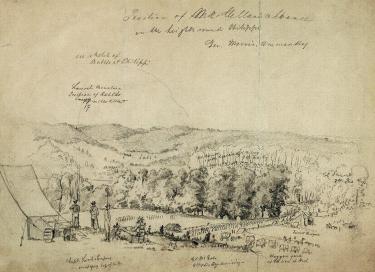

Not many people can know the considerable legacy of James Edward Hanger. Those who have lost a limb have been impacted by his work as a manufacturer and inventor in the field of prosthetics. James Hanger was born on February 25, 1843, in Churchville, Virginia, and had a typical Virginia childhood in rural Virginia. In 1860, enrolled as a student at Washington College (today’s Washington and Lee University) in Lexington, Virginia, when his life, like many other young men’s lives changed at the start of the Civil War. A bright engineering student, he left college enlisting in the Churchville Cavalry alongside two older brothers and four cousins. Soon after joining the army, he was placed on guard duty at a local farm near the Baltimore & Ohio Railroad in West Virginia. The very next day, the first organized land action of the war took place during the Battle of Philippi, a small skirmish in where Federal forces attacked the Confederate soldiers. Within twenty minutes, the unprepared Confederates quickly fled, leading the skirmish to be referred to as “The Philippi Races." Though the battle was small in number and over in minutes, it affected the rest of James Hanger’s life. Over the course of the battle Hanger suffered a serious injury when he was in a barn and a six-pound ball crashed in and hit Hanger’s left leg near the knee. It “passed through six thicknesses of two or two and a half oak plank stall partitions and partially penetrated the seventh. There its momentum was exhausted, and the ball fell in the stall.”

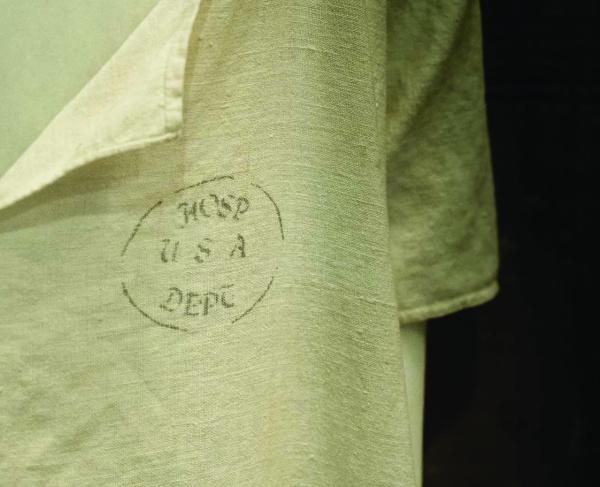

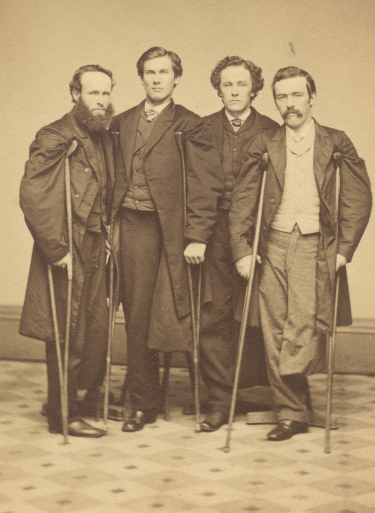

Gravely injured, Hanger was operated on by the 16th Ohio’s surgeon, Dr. James D. Robinson, and Dr. George W. New of the 7th Indiana Infantry. He had survived the surgery, but his leg was amputated seven inches below the hip bone. He recovered in Philippi under Union care becoming a prisoner of war. As a result of the skirmish, Hanger was one of the first recorded amputations at the start of the Civil War, one of over 50,000 in four years. Just a few months later, Hanger returned home to his family after a prisoner of war exchange in Norfolk, Virginia. Once he returned, Hanger started a new journey in his life trying to find his place in society as an amputee, which ultimately led him to his destiny.

Undergoing an amputation in the 19th century was a serious matter. Not only did it make life more challenging physically, but also mentally. Prosthetics that available in the 19th century were expensive, uncomfortable, and largely dysfunctional. Made of metal and wood, many were inflexible affecting an amputee’s mobility and function. Additionally, for many, the loss of a limb meant the loss of independence, and the ability to provide for a family in a factory or on the farm. In other words the loss of manhood. Hanger felt this when he said:

I cannot look back upon those days in the hospital without a shudder. No one can know what such a loss means unless he has suffered a similar catastrophe. In the twinkling of an eye, life’s fondest hopes seemed dead. I was the prey of despair. What could the world hold for a maimed, crippled man.

James returned to Churchville with a “peg leg” and struggled to find a place in society. Trying unsuccessfully to get a job in the Confederate War Department, he tried becoming a teacher and a jeweler, but those endeavors were also unsuccessful.

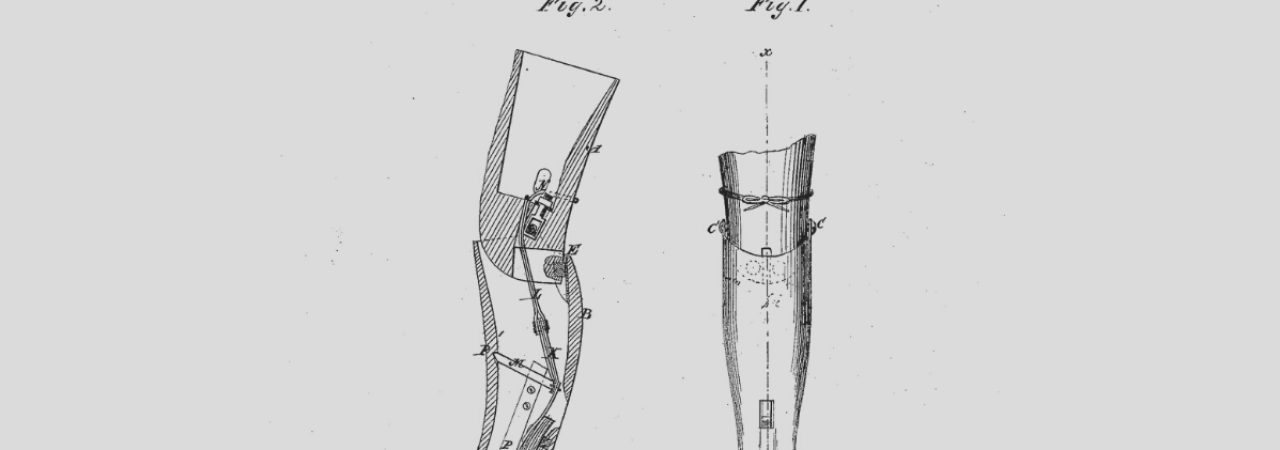

The prosthetic limb that was provided to Hanger by the Confederate Medical Department was awkward and painful. As an engineering student prior to the war, he worked to do something about it. Over the course of a few months, Hanger designed a better artificial limb using oak barrel staves, rubber bumpers, and nails to create a prosthetic limb that was able to bend at the knee and the ankle. With the success of his prototype, James took his “Hanger Limb” and opened up a shop in Staunton, Virginia, with one of his brothers to begin helping fellow Confederate soldiers with more comfortable prosthetic limbs at a more reasonable rate. Just over a year later, Hanger had filed and received a design patent (No. 155) for an “Artificial Leg” through the Confederate Patent office. A second patent was issued a few months later in August 1863. Working from his shop in Staunton, Hanger sent one of his limbs to the headquarters of the Association for the Relief of Maimed Soldiers with the promise to produce ten to fifteen limbs for a reasonable price: $200 for above-the-knee limbs and $150 for below-the-knee styles. By March 1864 Hanger was the leading supplier of artificial limbs to Confederate Veterans through the Association for the Relief of Maimed Soldiers and later through the Commonwealth of Virginia. While J. E. Hanger Artificial Limbs was busy during the Civil War, in the post-war era that business expanded exponentially with the flood of veterans looking to become customers.

In the years following the war, Hanger continued to expand and perfect his product, opening a branch of his business in Richmond and receiving a U.S. Patent (111,741) in February 1871. Business only grew in the following decades when J.E. Hanger became a family business. James and his wife, Nora McCarthy, married in 1873 and had twelve children. Several of his sons went into the family business and continued to help the business expand not only in location but in offerings as well. By 1910, the headquarters of J. E. Hanger Artificial Limbs moved to Washington D.C. and had established branches in Atlanta, Baltimore, Philadelphia, Pittsburgh, and St. Louis. By the turn of the century the “Hanger Limb” was one of the most popular prosthetic limbs and it was winning awards. In 1881 it won International Cotton Exposition in Atlanta and the 1907 Jamestown Ter-Centennial Exposition. The company also began offering a variety of different products that the company patented including wheelchairs and beds specifically designed for the disabled.

During his lifetime, James Hanger’s work spanned not only the Civil War, but World War 1 as well. Though he retired from the company in 1905, he remained the president of the J.E. Hanger Company and in the midst of World War 1, traveled to Europe to observe the effects of the war in France and Europe and the current state of European prosthetics. Making that trip allowed Hanger to continue to make contacts that soon resulted in contracts to supply artificial limbs to allied soldiers, leading to new offices being established in Paris and London.

By the time of James Hanger’s death in 1919, he had built a company that later become a billion-dollar company that helps over half a million patients annually. By 1950, there were fifty branches in the United States and 25 in Europe. Today the company is known as Hanger Prosthetics and Orthotics and one of the leading prosthetic companies today helping people “become whole” again over 150 years later.

Further Reading

- Learning from the Wounded: The Civil War and the Rise of American Medical Science By: Shauna Devine

- Mending Broken Soldiers: The Union and Confederate Programs to Supply Artificial Limbs By: Guy R. Hasegawa

- Empty Sleeves: Amputation in the Civil War South By: Brain Craig Miller

- Life and Limb: Perspectives on the American Civil War By: David Seed, Stephen Kenny, and Chris Williams