Vicksburg

The Battle of Vicksburg

By mid-May, 1863, after months of “experiments,” battles, and movements up and down both sides of the Mississippi River, the Army of the Tennessee under Maj. Gen. Ulysses S. Grant finally approached the Confederate defenses of Vicksburg. The capture of the town was critical to Union control of the strategic river, and Grant’s proven reputation as a fighter hung in the balance. The climax of the campaign would occur along Grant’s 8-mile long front encircling the Confederate defenders.

On the evening of May 17, the defeated Confederates under Lt. Gen. John C. Pemberton poured into their lines around Vicksburg after their defeat along the Big Black River. Looking for a quick victory and not wanting to give Pemberton time to settle in, Grant ordered an attack. Of his three corps, only Maj. Gen. William T. Sherman’s XV Corps northeast of the city was in the proper position to move forward and could attack on the 19th. The focus of Sherman’s assault would be the Stockade Redan, named for a log stockade wall across the Graveyard Road connecting two gun positions. Here, the 27th Louisiana Infantry, reinforced by Col. Francis Cockrell’s Missouri Brigade, manned the rifle pits.

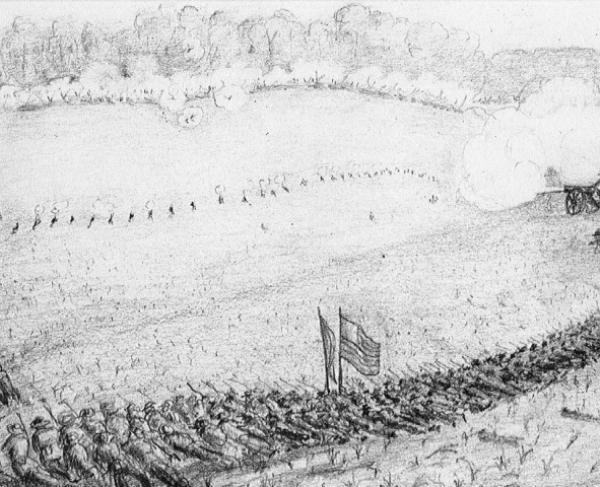

Sherman’s men moved forward down the road at 2:00 p.m., and were immediately slowed by the ravines and obstructions in front of the redan. Bloody combat ensued outside the Confederate works. The 13th United States Infantry, once commanded by Sherman, planted their colors on the redan but could advance no further. Captain Edward C. Washington, the grandnephew of George Washington, commanding the regiment’s 1st Battalion, was mortally wounded in the attack. After fierce fighting, Sherman’s men pulled back with 1,000 casualties. “We were swept away,” Sherman said, “as chaff thrown from a hand on a windy day.”

Undaunted by his failure on the 19th, Grant made a more thorough reconnaissance of the defenses prior to ordering another assault. Early on the morning of May 22, Union artillery opened fire and for four hours bombarded the city's defenses. At 10:00 a.m. the guns fell silent and Union infantry was sent forward along a three-mile front.

Sherman attacked again down the Graveyard Road, Maj. Gen. James B. McPherson’s XVII Corps moved against the center along the Jackson Road, and Maj. Gen. John B. McClernand’s XIII Corps attacked to the south at the 2nd Texas Lunette and the Railroad Redoubt, where the Southern Railroad crossed the Confederate lines. Surrounded by a ditch 10 feet deep and walls 20 feet high, the redoubt offered enfilading fire for rifles and artillery. The interior was divided by traverses at right angles to the outside walls and held several pieces of artillery. After bloody hand-to-hand fighting, the 22nd Iowa Infantry breached the Railroad Redoubt, captured a handful of prisoners, and planted their flag. The Iowans’ victory, however, was the only Confederate position captured that day. Timely reinforcements, led by Col. Thomas Waul’s Texas Legion, pushed McClernand’s men back to their lines and the fighting ended.

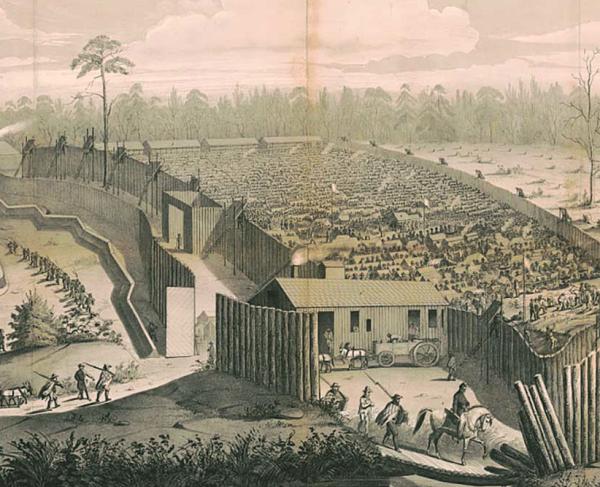

Grant’s unsuccessful attacks in May gave him no choice but to invest Vicksburg in a siege. Pemberton’s defenders suffered from shortened rations, exposure to the elements and constant bombardment from Grant’s army and navy gunboats. Reduced in number by sickness and casualties, the garrison of Vicksburg was spread dangerously thin. Civilians were particularly hard hit. Many were forced to live underground in crudely dug caves due to the heavy shelling. “We are utterly cut off from the world, surrounded by a circle of fire,” wrote Dora Miller in her diary. “The fiery shower of shells goes on day and night. People do nothing but eat what they can get, sleep when they can and dodge the shells… I send five dollars to market each morning, and it buys a small piece of mule meat. Rice and milk is my main food. I can’t eat the mule meat.”

By early June, Grant had established his own line of works surrounding the city. At thirteen points along his line, Grant ordered tunnels dug under the Confederate positions where explosives could be placed to destroy the rebel works. By the end of the month, the first mine was ready to be blown. The Confederates had built a redan where the Jackson Road crossed their lines east of the city, and the position there was manned by the 3rd Louisiana Infantry supported by artillery batteries. Union miners tunneled 40 feet under the redan from the James Shirley home, packed the tunnel with 2,200 pounds of black powder, and on June 25 detonated it with a huge explosion. After over 20 hours of hand-to-hand fighting in the 12-foot deep crater left by the blast, the Union regiments were unable to advance out of it and withdrew back to their lines. The siege continued.

By July, with food running out, Pemberton requested to talk with Grant. Both commanders met between the lines on July 3. Grant insisted on an unconditional surrender but Pemberton refused. Rebuffed, Grant later that night offered to parole the Confederate defenders. Pemberton and his generals agreed that those were the best terms possible. At 10:00 am the next day, Independence Day, some 29,000 Confederates marched out of their lines, stacked their rifles and furled their flags. The battle and siege of Vicksburg were over.

With the loss of Pemberton’s army and a Union victory at Port Hudson five days later, the Union controlled the entire Mississippi River and the Confederacy was split in half. Grant's victory boosted his reputation, leading to continued command in eastern Tennessee and ultimately his appointment as General-in-Chief of the Union armies.

See every dollar matched $6.50-to-$1 when you make a gift to nearly 32 acres of prime, unprotected battlefield land at Chickasaw Bayou and Champion...