One hundred and fifty years ago this spring and summer, the eyes of the world focused on Richmond, Va. The Peninsula Campaign, of which the week known as the Seven Days was the zenith, lasted almost five months, and few campaigns produced so many war-altering results. It simultaneously crushed Union momentum while stimulating an unbroken year of Confederate success. It also commenced the long, almost magical partnership between Confederate commander Gen. Robert E. Lee and his Army of Northern Virginia.

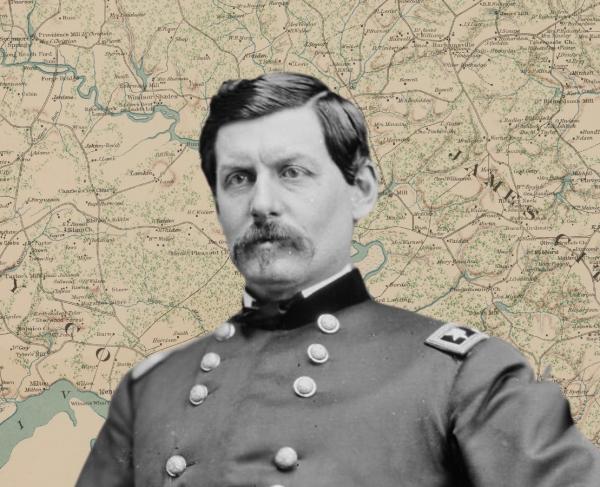

The Army of the Potomac's commander, Maj. Gen. George B. McClellan, faced many obstacles in his drive to capture Richmond and end the war that spring. He created many of those impediments himself, but several real problems beyond his immediate control contributed to his frustrations. The two largest — logistics and geography — combined to diminish the considerable manpower advantage he enjoyed over his Confederate counterpart.

Logistics can be defined as the business of keeping an army in the field in an adequate state of efficiency, with heavy emphasis placed on the supply of food and ordnance. Civil War armies also had to plan for a vast train of accompanying animals — officers’ mounts, teams to pull artillery, ambulances and wagons. The twin burdens of man and beast threw an immense responsibility onto McClellan's planning staff. A modern scholar of the campaign has calculated that by regulation, the quartermasters responsible for such matters had to find the means to bring a minimum of approximately 650 tons of material to the army every day.

When he approached Richmond in May 1862, travelling northwest up the Virginia Peninsula after launching his campaign at Fort Monroe near Hampton Roads in March, McClellan relied on the Richmond & York River Railroad to accomplish his logistical mandate. That line ran eastward from Richmond to White House Landing on the Pamunkey River, and then beyond to West Point on the York River. Oceangoing supply ships could reach White House Landing—the narrow Pamunkey was navigable that far upriver—and a reasonably convenient system evolved whereby White House Landing became one of the world’s busiest ports, and the Richmond & York River became one of the world’s most active railroads.

The railroad, however, was (and still is) a single track. To reduce the strain on the overtaxed railroad, work parties escorted wagon trains from White House Landing to the front, huge parties of axmen often combating the intolerable mud by building new roads from scratch as they advanced. This scheme reduced the strength of the army, exhausted army mules and provided only modest relief to the supply problem. There is some thought among historians today that if the Confederates had not driven McClellan from Richmond's door in June, his staggering supply apparatus might have collapsed within a few weeks anyway.

By the middle of May, when the Federal army lay about four miles east of Richmond, McClellan’s other problem, geography, came to the forefront. The swampy Chickahominy River bisected his line, with the northern portion stretching toward Ashland, awaiting long-promised reenforcements from Maj. Gen. Irvin McDowell's command at Fredericksburg. Although McClellan made noisy protests, then and afterward, about the delay in receiving help from McDowell, the railroad’s location also necessitated this configuration. The Richmond & York River crossed the Chickahominy near Bottom’s Bridge on its way to the front, and to protect that long line McClellan needed strong forces on both sides of the river.

A botched Confederate offensive at Seven Pines/Fair Oaks on May 31 and June 1, 1862, failed to alter the situation, at least from the perspective of anyone looking at a map. But during the fighting, Confederate commander Joseph E. Johnston was wounded, enabling Robert E. Lee to replace him at the head of the Confederate army. Within four days Lee had drafted a scheme to relieve Richmond — a plan that proved to mix controlled aggression with daring risks. Thomas J. “Stonewall” Jackson, then near the zenith of his notoriety, served as the trigger for the offensive. He carried his army by rail and forced march across central Virginia and into position on McClellan’s dangling flank north of Richmond. Lee hoped to unite with Jackson north of the Chickahominy and fall upon McClellan’s exposed flank; or, at the very least, use Jackson to turn the Union army’s line, threaten the railroad and force McClellan away from Richmond. Victory by maneuver would have pleased Lee, as would a pitched battle in the countryside east of the city.

McClellan knew of Jackson’s approach several days before “Stonewall” arrived, but inexplicably took no steps to counter the threat. Instead the army commander seemed almost resigned to his fate. Good work by Union cavalry slowed Jackson’s approach, though, and when Lee unleashed his offensive on the afternoon of June 26 it looked nothing like the carefully choreographed movement he had designed. Rather, Lee launched limited and entirely unsuccessful attacks against a Federal position near Mechanicsville, at Beaver Dam Creek. For a few brief hours, most of the Union army lay south of the Chickahominy, facing Richmond, while most of the Confederate army was concentrated north of the river. McClellan’s critics have excoriated him for not seizing that moment of opportunity, forgetting that he knew very little of the particulars and ignoring his legitimate worries about the pending loss of his army’s supply line.

Confronted with bad news from every sector, and virtually defeated before he started, “Little Mac” determined to withdraw his army from the outskirts of Richmond and move it to a new and safer base on the James River. The balance of the Seven Days’ Battles, fought between June 27 and July 2, saw the two armies fighting not to decide the fate of Richmond, but rather to determine the extent of the Union army’s suddenly inevitable defeat.

On the 27th, at Gaines’ Mill, Lee assembled more than half of his army, joined it with Jackson’s troops and fell upon McClellan’s rearguard along the Chickahominy River. Fitz John Porter and the Federal V Corps fought well under miserable circumstances with their backs to the river, resisting long enough to escape southward overnight. Gaines’ Mill is notable as Lee’s first victory as commander of the Army of Northern Virginia; the triumph cost him nearly 9,000 casualties, but it set the tone for the rest of the campaign and made it evident that Richmond’s hour of immediate danger had passed.

Once committed to his line of retreat, McClellan hurled himself into the operation with an energy rarely seen in previous weeks. He destroyed millions of dollars of supplies and abandoned at least 2,500 sick and wounded soldiers due to lack of transportation. However, he also demonstrated great ability in coordinating his retreating columns, extracting the balance of his army intact. A modest fight at Savage’s Station on June 29 preceded a major action at Frayser’s Farm, or Glendale, on June 30. On that afternoon Lee aimed four converging columns against a congested road intersection some three miles north of the James River. McClellan arranged half his army in an arc west of the crossroads, but carelessly left it exposed and leaderless.

On the Confederate side James Longstreet’s and A.P. Hill’s two divisions did most of the fighting, charging the western face of McClellan’s perimeter on both sides of the Long Bridge Road. Brig. Gen. George McCall’s division of Pennsylvanians, later buttressed by the divisions of Maj. Gens. John Sedgwick and Phil Kearny, mounted a desperate resistance. Hand-to-hand fighting swirled around little knots of isolated Union artillery. By sunset, Lee’s infantrymen had captured more than a dozen cannon and were masters of the field, but they had failed to drive any permanent wedge into the Federal army’s line of retreat.

Overnight the Union army retreated another mile to the defensible heights at Malvern Hill. Warships of the U.S. Navy lay nearby on the James River. Secure and comfortable at last, McClellan hoped that Lee would be imprudent enough to attack the virtually unconquerable position at Malvern Hill, giving the Union army a chance to end the campaign with a victory. Lee obliged, seduced into the folly of piecemeal assaults up the hill by a combination of inept staff work and a series of terrible misunderstandings.

Federal artillery traditionally gets the credit for destroying the Confederate attacks at Malvern Hill and, indeed, few Civil War battlefields had terrain more suitable for the effective employment of cannon. The infantry divisions of Brig. Gens. Darius Couch and George Morell, from the IV and V Corps, respectively, also saw heavy action against occasional fragments of Confederate brigades bold enough to reach musket range. No attacking unit breached the Union line, and sunset arrived none too soon for the defeated Army of Northern Virginia.

Few Civil War battles were as decisive as Malvern Hill, and few victories so hollow, since the Federal triumph there had precisely no impact on the course of the campaign. McClellan resumed his retreat overnight, hurrying to Harrison’s Landing on the James River, where he could feed his army, evacuate his legions of sick and wounded and rebuild his command. The following day, July 2, Lee determined that McClellan’s offensive had ended; Richmond was saved for the moment, and even the most optimistic Unionist recognized that Virginia was far from being conquered.

With Lee, a bold and innovative commander, at the helm, Confederate forces soon seized the initiative, launching the offensive that would culminate nine weeks later in the Maryland Campaign. Southern victories won in the next year would be among the most dramatic of the war.

Help raise the $429,500 to save nearly 210 acres of hallowed ground in Virginia. Any contribution you are able to make will be multiplied by a factor...

Related Battles

6,800

8,700

3,797

3,673

2,100

5,600