Petersburg

Assault on Petersburg

City of Petersburg, VA | Jun 15 - 18, 1864

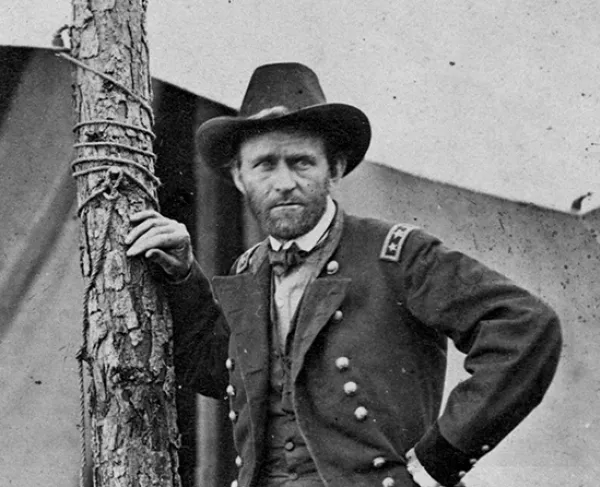

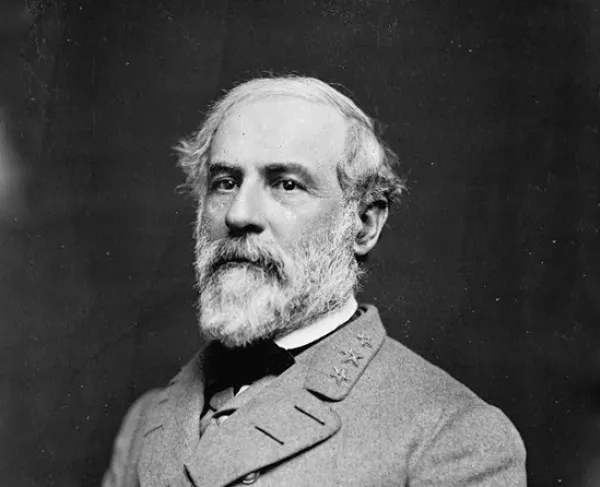

Ulysses S. Grant’s assault on Robert E. Lee’s armies at Petersburg failed to capture the Confederacy’s vital supply center and resulted in the longest siege in American warfare.

How it ended

Although the Confederates held off the Federals in the Battle of Petersburg, Grant implemented a siege of the city that lasted for 292 days and ultimately cost the South the war.

In context

General Ulysses S. Grant’s inability to capture Richmond or destroy the Confederate Army of Northern Virginia during the Overland Campaign (May 4–June 12, 1864) caused him to cast his glance toward the critical southern city of Petersburg. His strategic goals shifted from the defeat of Robert E. Lee's army in the field to eliminating the supply and communication routes to the Confederate capital at Richmond.

The city of Petersburg, 24 miles south of Richmond, was the junction point of five railroads that supplied the entire upper James River region. Capturing this important transportation hub would isolate the Confederate capital and force Gen. Robert E. Lee to either evacuate Richmond or fight the numerically superior Grant on open ground.

From June 15–18, 1864, Confederate general Beauregard and his troops, though outnumbered by the Federals, saved Petersburg from Union capture. The late appearance of Lee’s men ended the Federals’ hopes of taking the city by storm and ensured a lengthy siege. For the next nine months, Grant focused on severing Petersburg’s many wagon and rail connections to the south and west. He eventually attacked and crippled Lee’s forces, forcing the South to surrender at Appomattox on April 9, 1865.

After the crushing Union defeat at Cold Harbor, Grant uses stealth and deception to shift his army south of the James River. His troops begin crossing the river both on transports and a brilliantly engineered 2,200-foot-long pontoon bridge at Windmill Point on June 14. By the morning of June 15, Grant is ready to launch his attack.

Standing in his way is the Dimmock Line, a series of 55 artillery batteries and connected infantry earthworks that form a 10-mile arc around the city. However, with Lee still defending Richmond, a scratch force of only 2,200 soldiers under Confederate general P. G. T. Beauregard stand guard in Petersburg’s eastern defenses—from Battery 1 on the Appomattox River to Battery 16 nearly three miles to the south.

June 15. Union general William F. "Baldy" Smith cautiously leads his Eighteenth Corps westward from City Point. Smith delays his assault until 7:00 p.m., expecting the momentary arrival of Gen. Winfield S. Hancock’s Second Corps. Once under way, the Union attack proves anti-climactic. Federal troops gain the rear of Battery 5, throwing the defenders from the Twenty-sixth Virginia and a single battery of artillery into a panic. Batteries 3 through 8 also fall. Batteries 6 through 11 are captured by U.S. Colored Troops, commanded by Brig. Gen. Edward Hinks. Colonel Joseph Kiddoo, commanding the Twenty-second U.S. Colored Troops, later notes in his report that the “officers and men behaved in such a manner as to give me great satisfaction and the fullest confidence in the fighting qualities of colored troops.” After dark, Smith, joined at last by Hancock, decides to postpone further offensive action until dawn.

June 16. The Union Second Corps capture another section of the Confederate line. The Confederates lose Batteries 12 through 14.

June 17. The Union Ninth Corps gains more ground, but the fight is poorly coordinated. That night, Beauregard digs a new line of defense closer to Petersburg that meets up with the Dimmock Line at Battery 25, and Lee rushes reinforcements from other elements of the Army of Northern Virginia.

June 18. The Union Second, Ninth, and Fifth Corps attack but are repulsed with heavy casualties. The 850 men of the First Maine Heavy Artillery advance across a cornfield and straight into Confederate fire. Supporting units fail to protect their flanks. Within ten minutes, 632 men lay dead or wounded on the field. It is the largest regimental loss of the entire Civil War. With Confederate works now heavily manned, the opportunity to capture Petersburg without a siege is lost.

8,150

3,236

After four days of fighting with no success, Grant begins siege operations. Grant’s strategy is to surround Petersburg and cut off Lee’s supply route to the South. As he attacks Petersburg, other Union troops simultaneously attack around Richmond, which strains the Confederacy to the breaking point. During the 10 months of the siege, both armies endure skirmishing, mortar and artillery fire, poor rations, and intense boredom. By February 1865, Lee has only 45,000 soldiers to oppose Grant’s 110,000. Grant continues to order attacks and cut off rail lines. On April 2, Union forces launch an all-out assault that cripples Lee’s army. That evening, Lee evacuates Petersburg. Lee surrenders to Grant at Appomattox Court House a week later.

Captain Charles Dimmock of the Confederate Corps of Engineers designed the impressive ten-mile trench line that stretched around Petersburg in a "U" shape and was anchored on the southern bank of the Appomattox River. The fortifications held 55 artillery batteries and the walls reached as high as 40 feet in some areas.

Work on the defense line began in the summer of 1862. Under the orders of Maj. Gen. Daniel H. Hill, Dimmock used soldiers and enslaved laborers to execute the plan. Some 264 enslaved people from Virginia's Eastern Shore and more than 1,000 from North Carolina dug the fortifications. But progress on the defenses was continually hampered by a shortage in manpower. By December 1862, Dimmock asked the Petersburg Common Council for "200 negroes" to perform more labor. The slaves were "to report each morning upon the work … at eight o'clock [and] to be dismissed and permitted to return home at 4 p.m.," which he saw as a means to preserve the slaves' health from "nefarious discomfort and exposure of camp life."

Labor on the Dimmock Line continued through the rest of 1863. Captain Dimmock wrote that by late in July 1863, the Dimmock Line was "not entirely completed, but sufficiently so for all defensive purposes." Due to movements by Union troops late in the spring of 1864, work stopped on the Dimmock Line. Though incomplete, the fortifications were an initial obstacle to Union troops as they descended on Petersburg in June 1864. But once the city was under siege by the Federals, the trenches of the Dimmock Line proved to be as much of a prison as a protection for the exhausted and hungry Confederate troops trapped there throughout the winter.

African Americans served as soldiers and laborers for both the Union and Confederate armies in the battle and siege at Petersburg. Petersburg was considered to have the largest number of free Blacks of any Southern city at that time. About half of the city’s the population was Black of which nearly 35 percent were free. Before the battle and siege of Petersburg, both freedmen and slaves were employed in various war functions, including working for the numerous railroad companies that supplied the South.

Once the siege began in June 1864, African Americans continued working for the Confederacy. In September of that year, Confederate general Robert E. Lee asked for an additional 2,000 Blacks to be added to his labor force. In March 1865, as white manpower in the army dwindled, the desperate Confederacy called for 40,000 slaves to become an armed force. A notice in the April 1, 1865, Petersburg Daily Express read, "To the slave is offered freedom and undisturbed residences at their old homes in the Confederacy after the war. Not freedom of sufferance, but honorable and self won by the gallantry and devotion which grateful countrymen will never cease to remember and reward." However, the war ended soon after this offer was made.

Black troops in the Union army, including some freedmen and some former slaves from the southern states, had already distinguished themselves before the action at Petersburg. During the war nearly 187,000 African Americans served the Union. Of those, the greatest concentration of United States Colored Troops (U.S.C.T.) was at Petersburg. In the initial assault on the city on June 15, a division of U.S.C.T.s in the Eighteenth Corps helped capture and secure a section of the Dimmock Line. The other division at Petersburg was with the Ninth Corps, which fought in the Battle of the Crater on July 30, 1864.

In December 1864, all the United States Colored Troops around Petersburg were incorporated into three divisions and became the Twenty-fifth Corps of the Army of the James. It was the largest Black force assembled during the war and ranged between 9,000 and 16,000 men. During the Petersburg Campaign, U.S.C.T.s would participate in six major engagements and earn 15 of the 16 total Medals of Honor awarded to African American soldiers in the Civil War.

Petersburg: Featured Resources

All battles of the Richmond-Petersburg Campaign

Related Battles

62,000

42,000

8,150

3,236