Frances Clayton

In 1863, Frances Louis Clayton – also known as Frances Clalin or Jack Williams – sought help to receive back pay and bounty money owed to her and her deceased husband. She traveled around the Midwest as she headed from Missouri to Minnesota; from Minnesota to Grand Rapids, Michigan; from Grand Rapids to Quincy, Illinois; and from Illinois to, presumably, Washington, D.C. to locate someone with the authority to grant her request. Along the way, she spoke to reporters about her previous double life as a Union soldier.

Before the Civil War, Frances lived with her husband in Minnesota. When the fighting began, the couple set off to Missouri to enlist, hoping that enlisting a state away could help disguise Frances’s identity. Her husband enlisted under his real name, which has been recorded as “John” or Elmer” in different sources, and she donned the name “Jack Williams.” They joined a Missouri regiment that was mustered in St. Paul and for another twenty-two months fought side by side. At the Battle of Stones River from December 31, 1862 to January 2, 1863 their service came to an end. In this assault, General William Rosecrans helped win Union control on Central Tennessee while Frances’s husband succumbed to a bullet on the front lines. Forced by the ensuing battle, Frances told reporters that she had to step over his corpse during the conflict. Shortly after this fateful day, she reported her deception and was discharged from the army. Even though she was injured three times during the eighteen battles she fought in, she notes that her identity was never revealed.

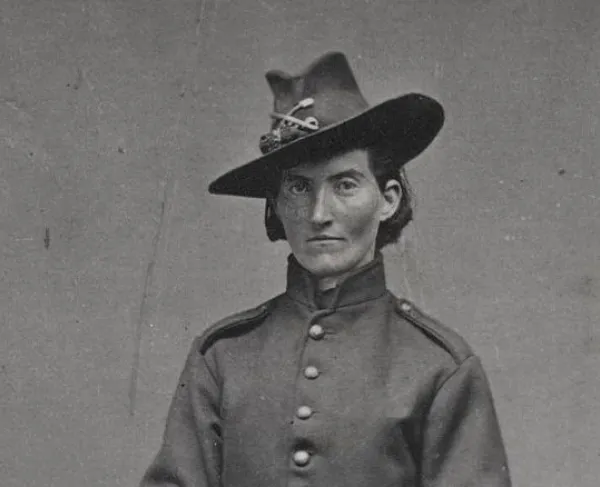

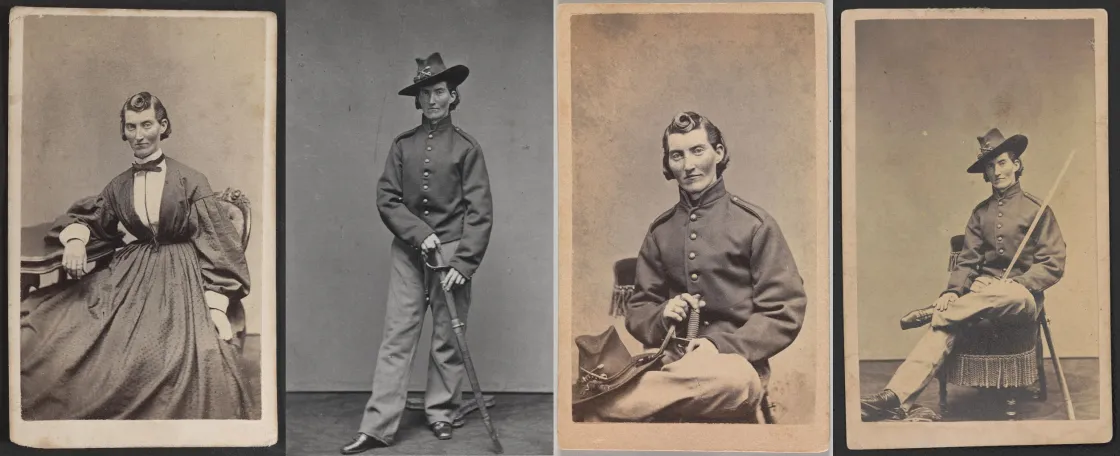

From 1863 to 1865, her name appeared in newspaper articles reiterating these stories. In addition, she had pictures taken of her in and out of Union military dress in 1865 by Samuel Masury at his photography studio in Boston, Massachusetts. These pictures became several of the most well-known photographs of women soldiers in the Civil War. However, the authenticity of her story has been questioned by historians. Several of the newspapers have contradictory information, such as what regiment she served in and which battles she fought in, that historians have not been able to verify with archival evidence. Also, newspapers focused on her cross-dressing more than on her service to the Union Army. There are no records revealing if she ever received the pension she sought or where she went after 1865. Because of the lack of evidence, some historians wonder if she did fight or if she fabricated the story for money and fame.

If she did fight in the Civil War as a female soldier, then she became part of the ranks of Albert Cashier, born “Jennie Hodgers” who fought for the 95th Illinois Infantry; Loreta Janeta Velazquez, who served as soldier and spy in the Confederacy; Sarah Rosetta Wakeman, who enlisted as “Private Lyons Wakeman,” and numerous other women soldiers who have been lost to history.