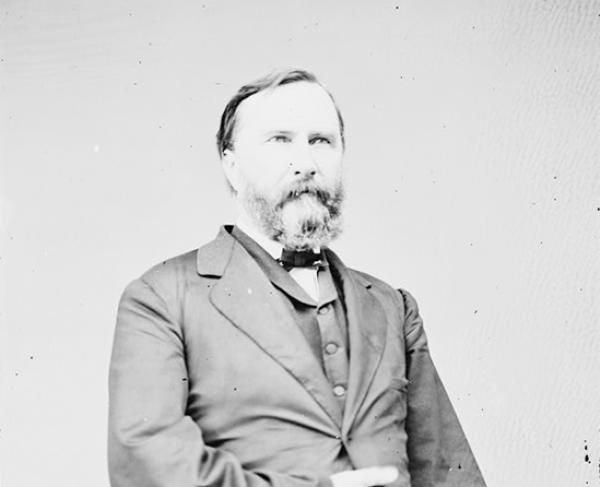

James Longstreet

Perhaps no Confederate officer is surrounded by more controversy than James Longstreet. Called “Old Pete” and “My Old War Horse” by Gen. Robert E. Lee, Longstreet was Lee’s trusted advisor and friend. But, after the war, Longstreet became the target of many “Lost Cause” attacks. His letters to the New Orleans Times, his support of the Republican Party, and his memoirs served to alienate many Southerners.

Longstreet was born in South Carolina, but spent much of his childhood at the home of his uncle, Augustus Baldwin Longstreet in Augusta, Georgia. “Uncle Gus” may have been influential in Longstreet’s early life as a fervent proponent of states’ rights. Longstreet went on to attend West Point, where he graduated fifty-fourth out of sixty-two cadets in the class of 1842. At the academy Longstreet befriended a young man from Ohio, Ulysses S. Grant, and after graduation both officers would be assigned to the 4th U.S. Infantry.

Like many future Civil War generals, Longstreet’s first real war experience came during the Mexican War. From 1846 to 1848 Longstreet rendered distinguished service in some of that war's most important battles including Vera Cruz, Churubusco, and Chapultapec, where he was wounded. Recognized for his bravery, Longstreet would also serve alongside his long-time friend and future subordinate George Pickett. Following the close of the conflict, he continued his army career, participating in the Indian Wars and rising to the rank of major by 1858.

At the outbreak of the Civil War, Longstreet, then serving in New Mexico Territory, resigned his commission after nearly twenty years of service. He was very quickly appointed Brigadier General under P.G.T. Beauregard and reported for duty in July of 1861. Following his first action at Blackburn's Ford, Longstreet received praise for his coolness under fire and the manner in which he inspired his men. Longstreet and Thomas “Stonewall” Jackson were both promoted to Major General under Joseph E. Johnston in October 1861. Following his promotion Longstreet commanded a division of six brigades–the nucleus of what would eventually become the First Corps of the Army of Northern Virginia.

In January of 1862 he was dealt a devastating blow when three of his children died in rapid succession from scarlet fever. In spite of this terrible news, Longstreet performed admirably during the Peninsula Campaign, often serving as the rearguard for Johnston's retreating army. At the Battle of Williamsburg in May 1862, General Johnston reported that he was “a mere spectator, for General Longstreet’s clear head and brave heart left me no apology for interference.” However, during the May 31 – June 1, 1862 Battle of Seven Pines, Longstreet bungled his orders and mismanaged the battle itself. General Johnston was seriously wounded and command eventually devolved on Robert E. Lee, then serving as senior military advisor to President Jefferson Davis. Longstreet quickly won General Lee’s trust with his performance at the battles of Glendale and, the following day, Malvern Hill. In a campaign that foiled the Union attempt to seize Richmond, Lee wrote that “Longstreet was the staff in my right hand.” That August, at Second Manassas, Longstreet’s wing of 28,000 men counterattacked the Union forces in what the National Park Service calls “the largest, simultaneous mass assault of the war. The Union left flank was crushed and the army driven back to Bull Run.” Longstreet was also noticed for his excellent performance the following month at Antietam, and his extraordinary coolness under fire continued to be a trademark.

When Jackson's Corps was assimilated into the Army of Northern Virginia, Longstreet was promoted to Lieutenant General and his corps was officially designated as the First Corps. During the incredibly bloody battle of Fredericksburg that December, Longstreet took advantage of the terrain to create an almost impenetrable defense along Marye’s Heights. From the heights above he used his artillery so effectively that no Union soldiers came closer than 30 yards to the infamous stone wall. From February to April 1863, Longstreet led two of his divisions to Southeast Virginia for the collecting of food and forage, and was therefore not present at the battle of Chancellorsville that May.

Longstreet did, however, rejoin Lee's Army for the second invasion of the North and the subsequent battle of Gettysburg. An outspoken proponent of western concentration, Longstreet was skeptical about the wisdom of the invasion. A further dispute between Longstreet and his commanding general over the nature of the campaign would only grow during the battle and its aftermath. While the corps commander was under the impression the army was to wage a defensive battle whenever possible, Lee, emboldened by his recent victory at Chancellorsville, insisted on attacking the numerically superior Army of the Potomac. Longstreet's Corps arrived on the field on July 2, 1863, one day after fighting had begun. After the Virginian denied him permission to flank the Federal army, two division's of the First Corps launched an attack on the Union left wing late in the afternoon of July 2. Despite initial success in breaking the Federal lines, Longstreet's men were denied victory, and casualties were high. Nevertheless, Lee was determined to exploit what he believed to be a weakness in the Union center and planned an assault for the following day. Longstreet, whose troops would spearhead the forlorn hope, voiced his strenuous objections to the plan, but was rebuffed. On July 3, in perhaps the war's most famous episode, troops from Longstreet's corps under Maj. General George Pickett charged across open fields to assault the Union center only to be repulsed, again at a great loss. For the remainder of his life, Longstreet would continually assert his opposition to Lee's command decisions at Gettysburg, much to the disdain of his fellow officers. This opposition, combined with allegations that he deliberately delayed the execution of Lee's orders, did much to tarnish Longstreet's reputation.

That autumn, Longstreet was sent west to the aid of the beleaguered Braxton Bragg. His troops arrived on September 20, just in time to rout a significant portion of the Union line at Chickamauga. Only the staunch resistance of George H. Thomas saved the Union army. The stubborn Gen. Bragg, however, was less than warm in his reception of Gen. Longstreet and his staff, especially when several of Longstreet's generals wished to have Bragg removed from command. President Davis would not remove Bragg, and Longstreet’s reputation was damaged. After a difficult winter–and an abortive attempt at independent command in East Tennessee–Longstreet and his men were happy to return to the Army of Northern Virginia in April 1864.

At the Battle of the Wilderness in May 1864, Longstreet and his men performed well, finding a hidden route from which they could attack Union forces, catching them in a deadly crossfire. On May 6th, in an incident very similar to Stonewall Jackson’s mortal wounding the year before, Longstreet was fired on by his own men. A minié bullet passed through Longstreet’s neck and shoulder, permanently paralyzing the general's right arm. Though he survived, he did not return to his corps until October, by which time the Confederate army was dead-locked in defending the besieged city of Petersburg. Longstreet was assigned to protect Richmond and the vital railroads that supplied the city.

On April 2, 1865, Union forces broke the Confederate line at Petersburg. When A. P. Hill was killed, Longstreet took command of his Third Corps. On April 9, 1865, however, Lee surrendered the Army of Northern Virginia to Ulysses S. Grant at Appomattox. Longstreet and Lee parted ways on April 12, 1865. Longstreet moved to New Orleans, and the two men never saw each other again.

In 1867, the New Orleans Times asked several leading citizens to comment on the newly passed Reconstruction Acts. Unwisely, Longstreet suggested that Southerners support the Republicans. He was praised in the North, but vilified in the South. In June 1868, he received his pardon – by act of Congress – with help from General Grant. He supported Grant for president, and when elected, Grant nominated Longstreet to be the Surveyor of Customs for the Port of New Orleans. For this last betrayal of the South he was labeled a “scalawag.”

Many of Longstreet’s actions after the war were controversial: his letters to the New Orleans Times, his support of the Republican Party, his acceptance of political appointments, and the fact that he commanded African-Americans (part of the New Orleans Metropolitan Police Force). Worst of all, he had dared to criticize Robert E. Lee’s leadership. Very quickly he became the target of “Lost Cause” attacks by Jubal Early, William Pendleton, Rev. J William Jones, and others. Longstreet spent the rest of his life attempting to restore his reputation. In 1889 he was dealt another huge blow. His home, Parkhill, burned to the ground in April. Then his wife, Louise, died in December.

Despite the many attacks by former officers in the Confederate Army, many men fondly remembered their days fighting under Longstreet. In 1890 the Washington Artillery—famous for their performance at Fredericksburg—insisted that Longstreet participate at the unveiling of Lee’s statue in Richmond and in 1892 at the 3rd annual United Confederate Veterans meeting former soldiers flocked to him. He spoke at the dedication of Chickamauga and Chattanooga National Military Park in 1895 and attended the 1902 centennial celebration at West Point.

Longstreet published his 800-page memoirs, From Manassas to Appomattox, in December 1895. In September 1897 he married 34-year-old Helen Dortch; although his family was not pleased with the marriage, Helen defended Longstreet’s name until she died in 1962. James Longstreet died on January 2, 1904, just days short of his 83rd birthday. He was buried at Alta Vista Cemetery in Gainesville, GA.