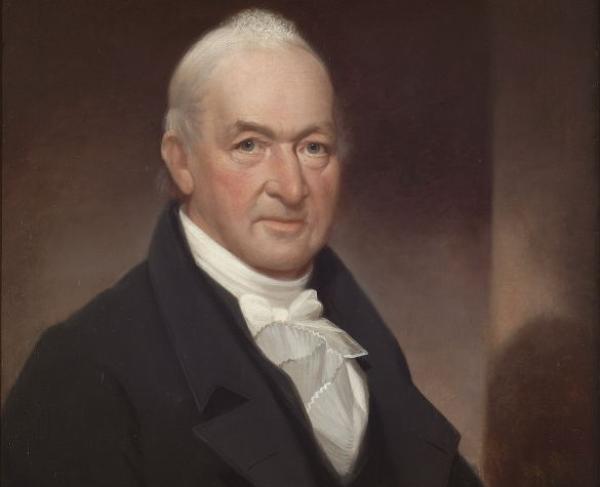

Thomas Conway

Thomas Conway is known as an officer with a name most connected to American Revolutionary War historiography with the loosely defined cabal that happened during the winter of 1777-1778. Yet, there was a reason this 41-year-old Irish-born former French Army colonel ended up fighting for American independence.

Born in Ireland to James and Julieanne Conway, the young Thomas spent his youth in France, after his family immigrated to the European continent in his formative years. By the age of 14 he had enrolled, likely with parental consent, in the Irish Brigade of the French Army. The French Army Irish Brigade had been formed the previous century, in May of 1690, when Jacobite regiments were exchanged with a larger equivalent of French infantry regiments to fight in Ireland. The British had largely ignored the recruitment of Irish for this brigade in French service until the Seven Years’ War. Anyone found in the service of the French king that was a British subject was labeled a traitor and faced execution if captured. The young Thomas’s involvement in this military unit showed his commitment to the military craft, regardless of the consequences.

By 1772, Thomas had risen to the rank of colonel in the French army and was still serving at that rank when the American Revolution broke out in Britain’s North American colonies. He, like many foreign officers, viewed the war in America as an avenue to quick advancement in rank. Conway availed himself at the earliest opportunity to receive an audience with the one American commissioner, Silas Deane, then in Paris. On December 14, 1776, Conway was on a ship headed across the Atlantic Ocean, after winning the approval of Deane, with a letter of introduction in his pocket. That letter also promised a high military rank to the ambitious officer of Irish descent.

When he arrived in America, he quickly proceeded to Philadelphia to meet with the Continental Congress. That political body awarded him a brigadier general commission on May 13, 1777, and instructed him to report to General George Washington. This rank did not befit the aspiring French officer who quickly pounced on the idea that Washington was the main impediment to his advancement to a major generalship, even though over twenty brigadier generals held commissions with an earlier date than he did. This line of reasoning eventually had major repercussions for Conway.

Although he was physically removed from Europe, Conway brought an exalted air of his own military competence and superiority with him across the Atlantic Ocean. After reporting to the Continental army, he was assigned a brigade that consisted of four Pennsylvania Regiments, the 3rd, 6th, 9th, and 12th Pennsylvania along with Spencer’s New Jersey Regiment. The brigade was in the division of Major General William Alexander, Lord Stirling. Conway did not endear himself to his fellow officers, first because he was part of an influx of European officers that were either granted generalships or promised high ranks, which alienated the homegrown officer corps. Secondly, he was a constant critic of the unmilitary-like bearing of the Continental Army, from its lack of uniformity to its coordination as an army. Lastly, his tendency to constantly drill his troops in a tendency that was not for the betterment of his command but to show off his military drill skills in front of his fellow officers.

On the battlefield at Brandywine and Germantown, Conway led his brigade with skill. At the former engagement on September 11, 1777, Conway’s Brigade, trading volleys with the British Grenadiers, part of the flanking column under Sir William Howe and Lord Charles Cornwallis. During the fighting that erupted between the Pennsylvanians and Grenadiers, the Marquis de Lafayette suffered his calf wound while entering the fray behind Conway’s command. A month later, at Germantown, Conway’s Brigade held the position of honor, the right flank, of Major General John Sullivan’s Brigade in the morning attack and he drove his brigade past the Chew House and toward the main British encampments before having to retire due to the command on his left giving ground.

His battlefield conduct showed the military bearing that had impressed the commissioners in Paris and led to his brigadier general commission. However, the off-battlefield demeanor eventually doomed Conway’s continued service with the Continental army. Disheartened with Washington, Conway sought to ingratiate himself with the rising star of Major General Horatio Gates, the victor of Saratoga in the fall of 1777. Conway became one of a growing number of luminaires, both in the military and Continental Congress, that believed a change in commanders of the main Continental army was needed. Conway continued his angling to all that would listen in Congress for a promotion to major general which would set him up upon his return to France with an elevated rank in that military force.

His name would soon grace the pages of history as the “Conway Cabal” which started with loose lips at a general’s headquarters by junior officers. One of the incriminating lines from a communique, which Conway had addressed to Gates read, “Heaven has been determined to save your Country; or a weak General and bad Counsellors would have ruined it.”

This letter, which the adjutant of Gates, James Wilkinson, tasked with bringing Gates’s official report of the victory at Saratoga to the congress stopped off to spend the evening at the headquarters of General William Stirling. Wilkinson, imbibing with Stirling’s staff officer Major William McWilliams mentioned the quote above, attributing it to Conway in his correspondence to Gates. Williams passed this information on to Stirling who routed it to Washington with the affirmation that, “such wicked duplicity of Conduct, I shall always’s think it my duty to detect.”

Washington, in turn, alerted Conway that he was privy to the information contained in the letter. Conway never admitted the truth to Washington that he was the author of such insinuations about Washington and his military leadership.

As October 1777 faded into history, Conway offered his resignation, however, Congress did not accept it and in turn promoted him to the rank of major general and the newly created inspector general position on November 14. To add to Washington’s frustrations, a Board of War was convened and to that administrative body was appointed Gates and Thomas Mifflin, who had resigned as quartermaster general and was not a fan of Washington, among the other four members. For the rest of the calendar year of 1777, the loosely formed “cabal” continued in their efforts to undermine Washington and potentially replace him with Gates.

Washington deftly maneuvered through this imbroglio, using a political acumen that would serve him well as the first president of the United States. When Conway and Gates refused to hand over the incriminating letter about Washington, the missive that contained the “weak general” line in January 1778 the “cabal” faded away. A groundswell of support for Washington among the officer corps at Valley Forge also eroded any potential command change.

Conway tried an old trick, offering his resignation again in March 1778. The first time, the ultimatum of losing an officer of Conway’s ability led the Continental Congress to grant him a promotion and the inspector generalship. Whatever political goodwill he had accrued had eroded by spring 1778, and this time, the Continental Congress accepted his resignation. On July 4, 1778, John Cadwalader, a pro-Washington militia leader from Pennsylvania grievously wounded Conway in the mouth in a duel. Upon recovery, Conway left the United States, sailing back to France after penning an apology to Washington, thus ending his connection with the American Revolution.

We can save three remarkable battlefield sites if we can raise $201,500. Every dollar you can donate to this cause will be multiplied by $23.80.

Related Battles

1,300

587

1,111

533