Second Winchester

Frederick County, VA | Jun 13 - 15, 1863

The second of three major battles fought in Winchester during the Civil War, this Confederate victory eradicated Federal opposition in the Shenandoah Valley and opened up the valley for Robert E. Lee's second invasion of the North.

How it ended

Confederate victory. Retreating Union forces were cut off and routed, with almost 4,000 Federals captured, in addition to ample supplies and munitions. With the garrison at Winchester eliminated, Lee and the Army of Northern Virginia were now free to travel down the valley into Maryland and Pennsylvania.

In context

The Battle of Second Winchester was the second engagement of the Gettysburg Campaign. After his victory at Chancellorsville, Lee decided to invade the North once again to provide relief to war-ravaged Virginia. He hoped to fight and win a decisive battle on Northern soil. Lee planned to march up the Shenandoah Valley to cross into Maryland, where the army's movements would be screened by both the Blue Ridge Mountains and Gen. J.E.B. Stuart's cavalry. Lieut. Gen. Richard S. Ewell's II Corps received the mission to clear the valley for the rest of the army, and at Winchester, succeeded in doing so.

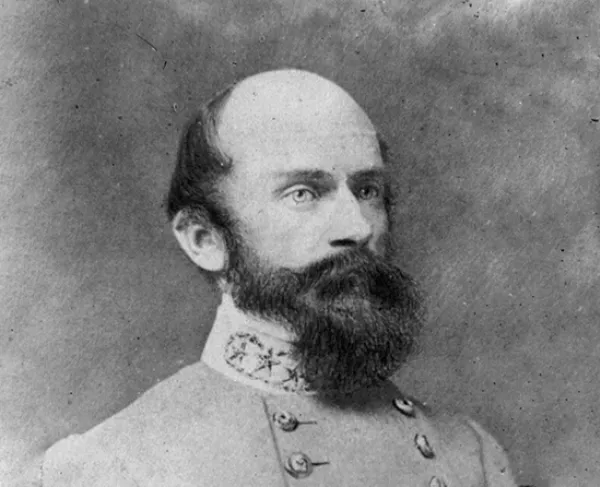

Although Chancellorsville was one of Lee's greatest victories over the Army of the Potomac, a crisis of leadership occurred with the death of Lt. Gen. Thomas J. "Stonewall" Jackson. Lee then divided the two Confederate corps into three, and designated Ewell to lead the second. His first assignment was to clear the Shenandoah Valley of Union opposition, specifically at Winchester, as the vanguard for the Army of Northern Virginia in its northward movement. After a brief delay at Brandy Station, Ewell's corps headed west and entered the Shenandoah Valley on June 12, 1863, at Front Royal. He sent one division to capture the Union garrison at Berryville and secure Potomac crossing sites, while the rest continued on to Winchester.

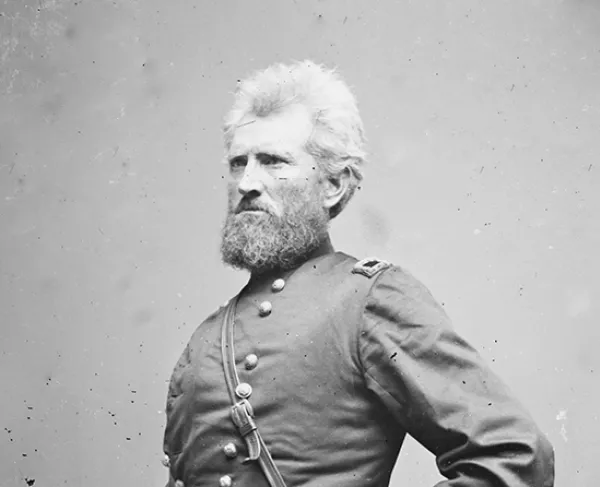

At the same time, Union Maj. Gen. Robert H. Milroy received reports of Confederate activity in the Shenandoah. Ordered by his superiors not to hold Winchester if impracticable, Milroy was skeptical of the perceived danger. His confidence received a boost by a series of earthwork forts around the city, constructed by Confederates early in the war and improved by both sides as the city changed hands (a British observer called Winchester the "shuttlecock of the Confederacy.") A skirmish on June 12 at Middletown finally alerted Milroy of the threat, causing him to send forces to occupy Pritchard's Hill, high ground two miles south of the city.

June 13. In morning, Confederate Maj. Gen. Jubal A. Early's division marched north towards Pritchard's Hill. After encountering resistance from Federals, two brigades flanked the hill, leading to two mile retreat to the outskirts of the city. Early's men were only stopped by blistering artillery fire from Bowers Hill and Milltown Heights, followed by an infantry counterattack led by Union Brig. Gen. Washington L. Elliot. Although the Confederate attack came to a halt from artillery as night fell, they now controlled all roads south and southeast of town. Milroy, realizing his precarious position, pulled all units closer to Winchester and the surrounding forts.

June 14. It was not long before Ewell's men seized Bowers Hill and placed their own guns to rain fire onto Winchester below. He also decided to attack West Fort, northwest of the town, to gain more crucial high ground. An infantry charge following an artillery barrage took the hill, including Federal batteries and supplies. Milroy was shocked; he had thought the threat was to the south and had sent the bulk of his men there, leaving West Fort undermanned and easily taken. An artillery duel ensued between Confederates at West Fort and Bowers Hill and Federals in Star Fort and Fort Milroy, the main fort. At the same time, Confederate Maj. Gen. Edward "Allegheny" Johnson's division closed in on the Martinsburg Pike, Milroy's last line of escape. At a council of war that evening it was decided to abandon Winchester.

June 15. At 1 a.m., the Federals began evacuating Winchester via the Martinsburg Pike towards Harpers Ferry. Wagons and artillery were left behind to keep the noise level to a minimum. All the men were soon evacuated. Unfortunately for Milroy and the Federals, Johnson's division had marched through the night to intercept them via the railroad cut that ran parallel to the pike, at Stephenson's Depot. At 3:30 a.m., Johnson's men attacked the lead elements of the evacuating Federals. Mass confusion ensued, as men struggled to form firing lines in the dark. Over two hours of fighting ensued, but soon Milroy's command was in danger of annihilation. He attempted breaking through on both Confederate flanks, but failed both times, as artillery neutralized the infantry. A defeat turned into a rout as Federals surrendered in large numbers or fled towards Harpers Ferry or Maryland.

4,443

266

The news of this Confederate victory, so close to the Mason-Dixon Line, stunned and frightened the North. In response, Secretary of War Edwin Stanton called for militia units to be federalized, President Abraham Lincoln called for 100,000 volunteers, and Pennsylvania Governor Andrew Curtain called for 50,000 volunteers. Milroy himself, after turning up in Harpers Ferry, was placed under arrest and subject of a court of inquiry. He was exonerated, claiming his defensive actions were key in timing the Battle of Gettysburg and subsequent Union victory - but he never again had a field command. Three Union soldiers received the Medal of Honor were their actions at Second Winchester. Additionally, the large amount of supplies captured by Ewell at Winchester justified Lee's plan to provision his army as they marched north, on the path to Gettysburg.

Winchester saw so much fighting because of the importance of its location. The city was the seat of Frederick County, Virginia, and an important market center. Nine roads, turnpikes, and telegraph lines converged on the city, as well as multiple railroads, including the Winchester and Potomac and the Baltimore and Ohio, and the Chesapeake and Ohio Canal. These roads linked the Ohio River Valley to the Eastern Seaboard and the nation's capital. Located at the very northern end of the Shenandoah Valley, controlling Winchester was key to controlling the valley's fruitful resources. Additionally, Winchester also held broader strategic implications for either army. For the Union, a loss of Winchester would mean Washington, D.C., was threatened, as the city lay north and west of the capital. It also threatened an invasion of Maryland and Pennsylvania. For the Confederates, Winchester was crucial to protecting Robert E. Lee's extended left flank, as well as protecting Richmond. One historian called Winchester "the key that locked the door to Richmond." Despite its key location, Winchester was difficult to defend, with its rolling hills making it easy for an attacking army to approach. Although some regional historians boast that Winchester changed hands over 70 times during the war, an accurate assessment puts that number closer to 11-13 times, with the city being controlled by the Union for 41% of the war, Confederates for 39%, and 20% between the lines. Nonetheless, Winchester changed hands more times than any other Confederate city in the war.

All battles of the Gettysburg Campaign

Related Battles

7,000

12,500

4,443

266