Thompson’s Station

Williamson County, TN | Mar 5, 1863

On March 5, 1863, Thompson's Station, Tennessee, was a no-man’s-land. It stood in the center of a battle line that stretched 1,100 miles, from the cavalry-strewn banks of Virginia’s Rappahannock River to the blue-clad battalions snaking their way down the Mississippi and beyond. The coming summer would shape the nation’s destiny as much as any other single season in American history. Here in Tennessee, the advantage was anyone’s for the taking.

The soldiers of Tennessee had rung in 1863 with the Battle of Stones River, also known as Murfreesboro. From December 31 to January 2, 71,000 men had fought to a grinding stalemate that left one in every three shot, clubbed, or stabbed. The frenzied engagement had defined the property line in Tennessee for the rest of the season. The generals of both armies entered winter quarters with their attention firmly fixed on assigning blame for various failures in the Stones River slaughter.

For Braxton Bragg, leader of the Confederate Army of Tennessee, the Battle of Stones River was an excruciating failure. Deceived into believing that William Rosecrans’s Union Army of the Cumberland was going to retreat after the first day of fighting, he was surprised to see the Federals stubbornly keeping the field, and ultimately ordered his own army to withdraw after launching an impetuous frontal assault that left the riverbank littered with the bodies of Kentucky veterans. Richmond was shocked by the reversal: Bragg had reported a complete victory on the evening of the first day.

Stones River was Bragg’s second bloody battle to end in tactical stalemate but strategic defeat. The first had come in October, 1862, at Perryville, Kentucky. Bragg’s poor handling of “high tide in the West” had generated almost enough ill will to depose the strict North Carolinian. Stones River precipitated a crisis in the Confederate high command that left the army almost literally paralyzed. Weary, freezing soldiers were scattered haphazardly around Murfreesboro, isolated and exposed, while their commanders met secretly and plotted to overthrow the chief.

William Rosecrans, the brusque Ohioan commanding the Union army from the state capital of Nashville, was facing his own problems. With the contending armies separated by barely more than a day’s march, his telegraph office was flooded with blunt directives from top brass: forward, forward, forward!

Rosecrans wired back that he was waiting for the rains to clear up. Storms had scoured the grey-green countryside for weeks and Rosecrans, a meticulous planner, did not want to launch a large-scale offensive only to end up trapped in knee-deep mud with his cannons, wagons, ammunition, and hospitalized men exposed to some of the most relentless horsemen in history. He was ready to make his first probes outward, but a large-scale offensive was still a long way off.

On the afternoon of March 4, 1863, a column of roughly 2,500 Federal soldiers rumbled out of Franklin, Tennessee, with orders to reconnoiter the rolling land around Spring Hill, which lay twenty miles south down the Columbia Pike. Only four miles into the march, they collided with Confederate outriders under the command of General Red Jackson.

The Union force -- Indianans, Michiganders, Wisconsinites, Ohioans, and six cannons, under the overall command of Colonel John Coburn – slowed and prepared for battle. The Confederates -- roughly 1,000 dismounted cavalrymen arrayed in the muddy highlands north of Thompson’s Station -- were content to give ground slowly and sweep reckless advance parties with musketry.

By sundown, Coburn was in command of the field and somewhat agitated. The Confederate withdrawal seemed like a ruse, and he wrote to headquarters to express concern that he was walking into a trap. He warily directed his men to make camp for the night, the sky brilliantly lit by bursting shells lobbed from Confederate cannons near Thompson’s Station. The next day would surely bring battle.

The battlefield was split in half, north to south, by the Columbia Turnpike. Thompson’s Station, the site of the main Confederate battle force, was in the southern sector of the field. North of town, Confederate pickets defended a pair of hills that rose on either side of the Turnpike. The main Union force camped north of these hills.

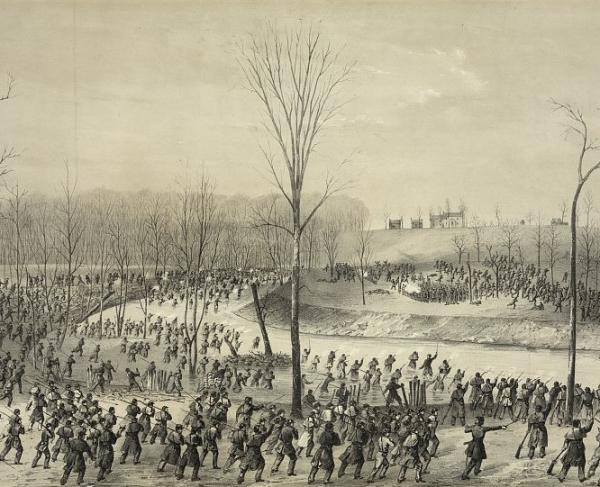

Moving forward at 8 a.m., Coburn’s Federals pushed stubbornly towards the Confederate advance line and drove it in, taking possession of the high ground overlooking Thompson’s Station. From here Coburn could see the formidable array of gray-coat veterans in and around the town, and he hastily ordered his artillery forward.

The Confederates ducked for cover as shells carved furrows down dirt roads and blew down sturdy walls. When they looked up, the Union attackers were almost on top of them. War cries and musketry cut the air as the Confederates rose up and counter-charged. At one point 17 year-old Alice Thompson dashed into the open and waved a Confederate battle flag aloft, exhorting the men to protect the town. The attacking party tumbled back to the hills bisected by the Turnpike and the fighting intensified as the Union guns banged away at the Southern pursuers.

At this point in the battle Coburn suffered a severe shock. Under some authority other than his own, the artillery and cavalry supports of his expedition quit the field. Suddenly outnumbered and outgunned, Coburn faced “a contingency against which all human foresight could not provide.”

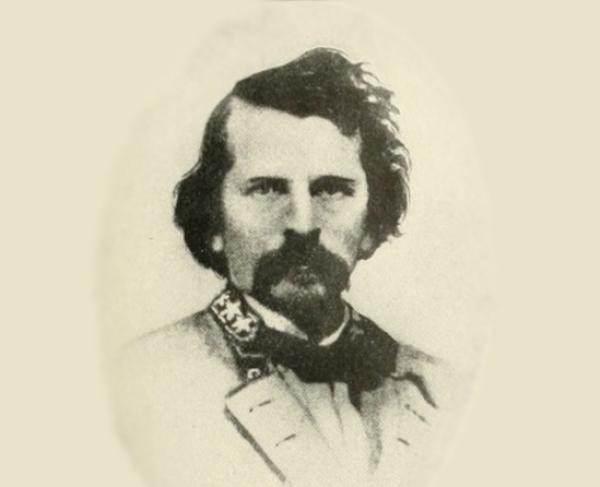

Nathan Bedford Forrest, fighting east of the Columbia Turnpike, seemed to sense the vulnerability in front of him. He shouted and cursed at his men to reform amidst the bloody confusion and led them on a wide march to the east and north before finally taking position in Coburn’s rear and cutting his line of retreat.

There was nothing now to do but hold, surrender, or die, so Coburn’s stubborn Midwesterners hunkered down on their ridge and began to beat back attacks from almost all sides. Forrest led three or four charges and lost one of his favorite mounts, Roderick, when the wounded horse broke free of the hospital and was killed searching for his comrade on the battlefield. The horse's death later inspired a poem, The General's Mount, by Nashville journalist Jack Knox.

A Confederate veteran later recalled that the carnage “continued … about five hours, and, so deadly and stubborn was the nature of the contest, that at times bayonets actually clashed, and hand to hand fights to the death were not uncommon.” In the end, Coburn’s exhausted and battered men surrendered.

With thousands of men taken prisoner and a minor scandal brewing over the surprise redeployment of Coburn’s cavalry and artillery, the Battle of Thompson’s Station was a minor fiasco for the Union army. It certainly did nothing to speed Rosecrans towards a general advance.

The Confederate veterans of Thompson’s Station knew that they had just won a striking victory. Their sacrifices were ill-served, however, by Braxton Bragg and the schemers in his camp. The most important lesson of the fight – that the Union army was beginning to uncoil and explore offensive options – was lost in the personal bickering. The Confederates remained dispersed and exposed, and they would pay a steep price for their oversight in the summer of 1863.

Recently, the Trust partnered with The Land Trust of Tennessee to assist the Town of Thompson’s Station in acquiring an important tract. In addition, the Trust continues to campaign for land around Williamson County, Tennessee, with notable successes at the Spring Hill and Franklin battlefields. In fact, the Williamson County preservation legacy demonstrates that battlefield reclamation can re-dedicate significant tracts of hallowed ground. In the words of local historian Gregory Wade, “it is a loss to all historians who watch an entire historical watershed disappear.”

Thompson’s Station: Featured Resources

Related Battles

2,500

1,000

1,906

300