Hanging Rock

Heath Springs, SC | Aug 6, 1780

The Battle of Hanging Rock occurred on August 6, 1780, as part of a Patriot drive to reclaim the southern colonies after the siege of Charleston, South Carolina. The Americans attacked the minimally defended British outpost at Hanging Rock, South Carolina, hoping to dislodge the British from the South.

How It Ended

Although the Americans withdrew, Hanging Rock is considered a Patriot victory. While the American forces suffered more casualties, The victory at Hanging Rock served to further embolden Patriot efforts to dislodge the British in the south.

In Context

Following the fall of Charleston in May 1780, the British established a number of outposts with the intention of restoring Royal authority over South Carolina’s population and resources. While the British sought to consolidate their gains, Patriot forces worked to weaken the enemy’s hold on the South. Confident that the British would be unable to quickly assemble a substantial number of troops to adequately defend any one outpost, General Thomas Sumter proposed small, calculated attacks on the British outposts. His ultimate goal: make it undesirable and unsustainable to remain at key strategic locations along the Santee and Wateree Rivers. One of these locations was at Hanging Rock – a crossroads between Camden, South Carolina and Charlotte, North Carolina.

In the hazy summer of 1780, South Carolina’s partisan wars were heating up as American detachments ransacked the string of British garrisons established by Lord Cornwallis. Patriots became increasingly bold in their attacks, especially after guerrilla forces destroyed a British detachment commanded by Captain Christian Huck on July 12. In late July, Patriot leaders from across the Carolinas met to plan further operations. It was decided that Patriot forces would focus their efforts on British outposts in the Catawba River Valley. The most northern of these outposts, located at Hanging Rock, (named after a local boulder that sat propped up on a slight elevation overlooking the nearby Hanging Rock Creek), guarded the Camden-Charlotte Road. Although it was an outpost, it did not have typical fortifications and instead was a garrison divided among three distinct encampments of Loyalist partisans and British troopers.

On July 30, American Colonel William Richardson Davie successfully ambushed a British unit in sight of their outpost at Hanging Rock, a diversion while partisan group General Thomas Sumter’s Patriots besieged the British post of Rocky Mount for eight hours 17 miles to the west. With 40 dragoons and roughly the same number of mounted riflemen, Davie’s force was far too small to take on Colonel Samuel Bryan’s 500 North Carolina Loyalist Militia. Instead, Davie focused his efforts on a garrisoned house near the fort at Hanging Rock. Using the similarities in dress, speech, and manner between his men and Bryan’s Loyalists to his advantage, Davie’s Mountain riflemen casually rode into three companies of Loyalist mounted infantry and opened fire. Anticipating the Loyalist flight, Davie circled his dragoons to cut off their retreat. All this happened in plain view of the main Loyalist encampment, and having routed a small number of Loyalists, Davie withdrew before reinforcements arrived.

Nearby, at Rocky Mount, Sumter and his men were thwarted in their attack by a thunderstorm and therefore, Sumter was as determined as ever to strike a blow. Once Davie’s forces returned, it was decided a full assault on Hanging Rock, which had minimal defenses and reduced its forces in light of Sumter’s attack, might lead to the evacuation of Rocky Mount altogether. On August 5, reinforced by Davie and nearly 800 militia, Sumter marched 16 miles through the night, stopping just short of Hanging Rock. Crossing Hanging Rock Creek at 6:00am, the attack began.

800

1,400

The garrison at Hanging Rock was under the command of Major John Carden, newly appointed commander of the Prince of Wales Loyal Volunteers. Carden earned his promotion after Lt. Col. Thomas Pattinson was found drunk by Lord Rawdon upon inspection of the encampment on July 29. The remaining forces consisted of Colonel Samuel Bryan’s North Carolina Tory militia, still reeling from Davie’s raid; mixtures of North and South Carolina Loyalist militia, and 160 Infantry of the British Legion, minus its commander, Banastre Tarleton.

Accounts differ as to how many of these mixed units were actually present during the battle. Some accounts state 1,400 troops, including 800 militia were among those encamped, while other accounts state the garrison had only 500 soldiers present the morning of August 6. Regardless of the number, the British mixed forces encamped south of and above Hanging Rock Creek, on hills, roughly positioned as a crescent, stretching along the Camden Road. These camps were divided among the mixed units, and were surrounded by open fields with scattered wooded areas, and defended by makeshift earthworks. Author William Dobein James described the British as being “secured by a strong position, a stockade fort and a field piece; on Sumter’s front the wood crossed the Hanging Rock Creek, running between lofty hills; on the right lay the British in open ground; on his left encamped the Tories on a hill side, covered with trees, and between them and the fort ran a small stream of water thro’ a valley covered with brush wood.”

Supported by Davie’s cavalry, Colonel Richard Winn was to assault the garrison. Sumter’s force was divided into four units under Colonels William Bratton, Edward Lacey, William Hill, and James Hawthorne. Men and boys without weapons took care of the horses, a 13-year-old Andrew Jackson among them, at the base of sheltering boulders in the creek valley. From Davie’s perspective, “The Regulars were posted on the right, a part of the British Legion and Hamilton’s regiment were at some houses in the center, and Bryan’s regiment and other Loyalists were some distance on the left and separated from the center by a skirt of wood. The British situation could not be approached without an entire exposure of the assailants.”

Davie’s column on the right consisted of his corps, “some volunteers under Major Bryan, and some detached companies of South Carolina refugees. Hill commanded the left composed of South Carolina refugees. Colonel Irwin commanded the center, entirely of the Mecklenburgh militia.” William Dobein James continued writing, “The South Carolinians formed the right and center; Steene commanded the right and Lacey and Lyles the center; the North Carolinians under Col. Irvin formed the left. Capt. McClure with 50 riflemen and Capt. Davie with 60 cavalry were thrown into the reserve…Capt. McJunkin was ordered to penetrate between the camps. Col. Lyles, Watson, and Ervin commanded the center and left divisions. They were ordered to enfilade and cut off the Regulars. Sumter, in person, led the center and left.” The Mecklenburg County, North Carolina forces totaled about 500 while the remaining 300 Americans hailed from South Carolina.

Approaching from the northwest, the three American divisions were supposed to attack the British position from the left, right, and center prongs. However, Patriot scouts misled the approaching columns of the center and right detachments, causing the entire forces to collide as they fell upon the North Carolina Volunteers on the right flank of the British camp. This was the fault of “the Guides, through ignorance or timidity,” reported Davie. Hill acknowledged, the “action commenced under many very unfavorable circumstances…as they had to march across a water course & climb a steep cliff, being all this time under the enemy’s fire.” McClure led his men through the valley of Hanging Rock Creek and ascended the bluff opposite the enemy’s encampment. The attacking forces “rushed forward right into [Samuel] Bryan’s camp, fired two rounds and then clubbing their muskets, rid the field. The Tories fled towards the British camp about a half mile distant,” wrote soldier Daniel Stinson. Bryan’s Tory militia had been completely overrun in a matter of minutes.

As these units fell back towards the British camp, located in the center of the garrison, the Legion infantry and members of Montfort Browne's corps (not to be confused with Col. Thomas Brown’s Rangers) formed a line of fire. The Legion infantry and the corps tried to make a stand behind a fence, located near a patch of thick woods. Browne's men fell back into the woods and for a moment had a tactically secured position to unleash musket fire under 50 yards. Sumter’s partisans soon overran them, taking the wooded positions for themselves. The entire camp was now in chaos. With the Provincials in full flight, leaving behind their artillery pieces, the Prince of Wales Regiment pushed a deadly fire into Sumter’s men, recapturing the field pieces. Amidst the intense fighting, Major John Carden became overwhelmed, lost his nerve, and turned over command of the crumbling forces to Legion Captain John Rousselet, who formed a hollow square on cleared ground, supported by the two fieldpieces. Sumter’s men refused to charge across open ground in the face of both artillery and musket fire. Some of the Legion and the North Carolina Volunteers, that were not in the British square, tried to reform to attack the partisans, but Davie’s dragoons moved behind the cover of the trees and charged them, eventually driving them out of their positions. The Tory fighters that remained were overtaken by nonstop American firepower. Hidden in the woods and using what cover they provided, Sumter’s riflemen soon left few British officers standing on the field. Dangerously low on ammunition, Sumter observed, “The action continued without intermission for three hours, men fainting with heat and drought.”

As the British encampment deteriorated, American militia rushed forward to seize precious supplies, including stores of rum. Soon enough, many of the soldiers were too inebriated to fall back into rank and gather for the continuing fight and Sumter lost the chance to completely rout the remaining British forces. The American strength of 800 now dwindled to about 250 remaining committed to the offensive. Hearing of the fighting, Colonel George Turnbull sent cavalry from his detachment of the British Legion from Rocky Mount to reinforce Carden. They ordered their men to extend their files to look larger than they were. Spying these forces assembling on the nearby Camden Road, Davie’s dragoons rode in, successfully chasing them off before they could effectively get into the action. With the outside threat now gone, and the bulk of his forces plundering the encampment, Sumter called off the attack. He watched as many walked off with what spoils they could carry, leaving the American commander to call for the rest of his forces to abandon Hanging Rock. The remaining Tory troops had lingered in plain sight of the Americans ransacking their garrison. In spite of their rout, they gave “three cheers for King George!” when the Americans retreated. Not to be outdone, they were answered with “three cheers for Washington, the hero of American Liberty.” Later, both sides flew a flag of truce to collect the dead and wounded still left on the battlefield.

53

200

Considering the numbers engaged in the Battle of Hanging Rock, the engagement was one of the bloodier battles of the American Revolution, at least for the British. Following the battle, the Prince of Wales Regiment was nearly wiped out, removing them as an effective fighting force. The British Legion had 62 men killed and wounded; all totaled the British suffered 25 killed and 175 wounded. Many Loyalists simply fled from the field upon the initial American charge. Sumter’s forces took 100 horses, 250 muskets and untold stores in the plundering. Had the American units kept their discipline and remained committed to offering deadly musket bursts into the encampment, Sumter likely could have captured more than just casks of rum and spare munitions; he could have taken hundreds of Tory prisoners while claiming Hanging Rock for himself. The battle was an American victory, but Sumter had failed to take the British garrison, missing the opportunity of fully removing the enemy from the field as many partisans would return to fight another day.

Sumter would later write, “The true cause of my not totally defeating them was the want of lead. Having been obliged to make use of arms and ammunition taken from the enemy. I had about twenty killed, forty wounded, two missing. I took seventy-three prisoners, forty odd of which were British, among whom were three commissioned officers. I brought off about one hundred horses and 250 stands of arms…We have got a great victory, but it will scarcely even be heard of, as we are but a handful of raw militia, but if we had been commanded by a Continental officer, it would have sounded loud in our honor.”

John Adair had been in the 3rd South Carolina Rangers when Charleston fell and served in 14 battles during the American Revolution. He concluded, “This I believe was the hardest fought battle during the war in the south.” The battle was also significant because it represented the first military experience for a young messenger serving Davie: Andrew Jackson.

Today, the site of Hanging Rock can be found in Heath Springs, South Carolina, known as Hanging Rock Battlefield Trail, directly off the Hanging Rock Creek. While the day’s fighting might seem inconsequential, it provided the opportunity for South Carolina militia forces to prove their meddle while also delivering a humiliating blow to the confidence of British military seniority in their garrisons. In the days ahead, the Battle of Camden on August 16, 1780, would loom large over the course of events in South Carolina, especially to the morale of American forces. For students of history, the smaller engagements like the one at Hanging Rock allows us to see the many moving parts of what a partisan war looked like and how the country was enveloped in a bitter fight of survival.

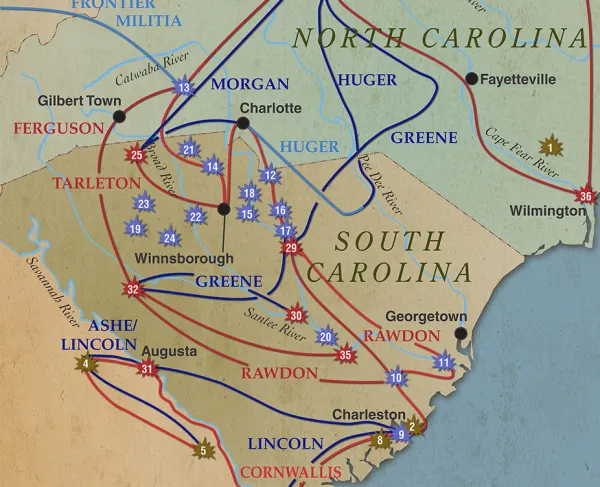

After the fall of Charleston, partisan forces formed throughout South Carolina to resist the British occupation. Throughout the summer of 1780, these groups equipped themselves with weapons and struck blows against British and Loyalist forces trying to gain footholds in the backcountry. Although not part of the Patriot army, these partisan groups aided the Patriot movements because they not only defeated British troops, but also managed to cut off British supply and communication lines. British General Cornwallis was forced to assign troops to fight these partisan groups, separating his men and delaying his movements into North Carolina. The partisan groups were often successful because they had a history of hunting and fighting on horseback in the backcountry, and therefore were highly skilled and mobile on horses. Furthermore, because they were skilled in hunting, and often fought with Native Americans, the men in these groups already had unconventional warfare experience and tactics that they used to their advantage. In late 1780, American General Nathanael Greene, saw the importance of these partisan groups and incorporated them into his plans for the future of the war.

In 1780, South Carolinian Andrew Jackson and his brother were encouraged to join the war effort by their mother as anti-British sentiment grew stronger throughout the Carolinas. The two brothers initially served as couriers for the American militia due to their young age. A 13-year-old Andrew Jackson served at the Battle of Hanging Rock, tending the horses of the partisan militia. He and his brother were captured by the British in April 1781, and both fell into poor health. His brother and mother both died from illness, leaving Jackson an orphan, and causing Jackson to blame their deaths on the British. After the American Revolution, he eagerly joined the war effort in the War of 1812 to fight the British and earned notoriety and praise for his victory at the Battle of New Orleans in December of 1814.

Hanging Rock: Featured Resources

All battles of the Southern Theater 1780 - 1783 Campaign

Related Battles

800

1,400

53

200