Horseshoe Bend

Alabama | Mar 27, 1814

The Battle of Horseshoe Bend, fought on March 27, 1814 effectively ended Creek resistance to American advances into the southeast, opening up the Mississippi Territory for pioneer settlement.

By 1812, internal hostilities engulfed the Creek nation, dividing a once strong tribe into two stratified factions, the Lower Creek, who were generally pro-American, and the Upper Creek, who resisted American interference with their traditional way of life. By adopting a quasi-European lifestyle consisting of agriculture, religion and diplomacy, Lower Creeks endeavored to preserve their tribal autonomy by following a precedent set by Cherokees in neighboring Georgia.

On the other hand, traditionalists from the Upper Creek nation strongly opposed the new American-backed National Council, which served as a medium between the Creek and the United States government. Although a derivative of traditional tribal decision making structures, the National Council was detested by Upper Creeks because of its expansion of U.S. power. The resultant rift is known today as the Creek Civil War.

By the summer of 1813, the violence had grown from minor infighting amongst the Creeks, into all-out civil war. In reaction to the chaos, Colonel James Caller of the Mississippi territorial militia mustered 180 men to ambush a band of Upper Creek sympathizing Red Sticks returning from Pensacola with British firearms and ammunition. The ensuing conflict came to be known as the Battle of Burnt Corn Creek. The event sparked a tinder box of retaliatory attacks by the Upper Creeks, triggering large-scale American involvement in the war and eventually the battle of Horseshoe Bend.

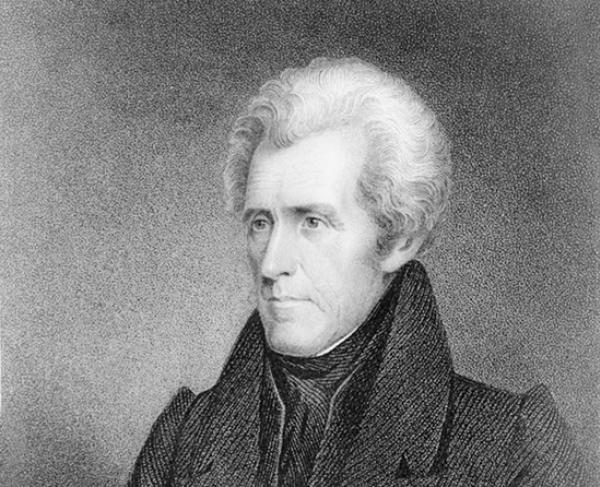

On the night of March 26, 1814, Major General Andrew Jackson and a contingent of 3,300 regulars, militiamen, Cherokees and Lower Creek camped six miles north of Horseshoe Bend. The Red Sticks, under direction of Chief Menawa, had fortified their village, Tehopeka, located on the peninsula created by the bend. The daunting log and mud breastwork at the neck of the peninsula made a frontal assault on Tehopeka virtually impossible. An impressed Jackson later described the fortification favorably, “It is impossible to conceive a situation more eligible for defense than the one they had chosen and the skill which they manifested in their breastwork was really astonishing.”

In the morning Jackson launched a two-pronged attack on Tehopeka. Knowing that he couldn’t assault the breastwork head on, he divided his force, sending his second in command General John Coffee and 1,300 militiamen, Lower Creeks and Cherokee on a wide flanking maneuver that would cross the Tallapoosa and surround the Red Sticks. Jackson commenced an ineffective artillery barrage at 10:30 a.m. while Coffee’s men positioned themselves across from Tehopeka.

Once organized on the adjacent banks of the river, Coffee ordered a small contingent to swim across the Tallapoosa and steal the Red Stick’s canoes. Once the canoes were secured, Coffee ordered Colonel Gideon Morgan’s Cherokee Regiment to traverse the river and attack the town itself.

Jackson, who was bombarding the breastwork on the opposite side of the bend, began hearing small arms fire and seeing smoke rising from Tehopeka. Coffee’s men had served as the diversion Jackson needed. Without hesitation he ordered the 39th U.S. Infantry, his most elite unit, to initiate a bayonet charge. Colonel John Williams led the assault accompanied by a young Sam Houston, the future patriarch of Texas. As soon as the 39th scaled the fortification the violence turned from a battle into a slaughter. Women and children were not exempt from the carnage and more than 200 fleeing Red Stick warriors were killed while swimming across the Tallapoosa to safety.

The battle of Horseshoe Bend was a disaster for the Red Sticks, with more than 800 of their 1,000 warriors killed in the fray. Even more significant, the Upper Creek nation had lost its last substantial fighting force. Chief Menawa was wounded seven times during the battle but miraculously escaped after playing dead until nightfall, crawling into a canoe and floating away on the Tallapoosa.

Following the defeat at Horseshoe Bend, the remaining warriors signed the Treaty of Fort Jackson, which ended hostilities and forced the Upper Creeks to cede over 20 million acres to the United States government, virtually half of what is today Alabama. Over the next 15 years, Alabama’s population exploded, growing from a sparsely populated wilderness with under 10,000 inhabitants in 1810, to one of the South’s most vital economic engines by 1830 with a population over 300,000. The Creek would never be able to regain their tribal autonomy and in 1830 with the signing of the “Indian Removal Act” by President Andrew Jackson, the remaining Creeks were forced onto reservations in Oklahoma on the “Trail of Tears.”

Horseshoe Bend: Featured Resources

Related Battles

2,000

1,000

276

1,063