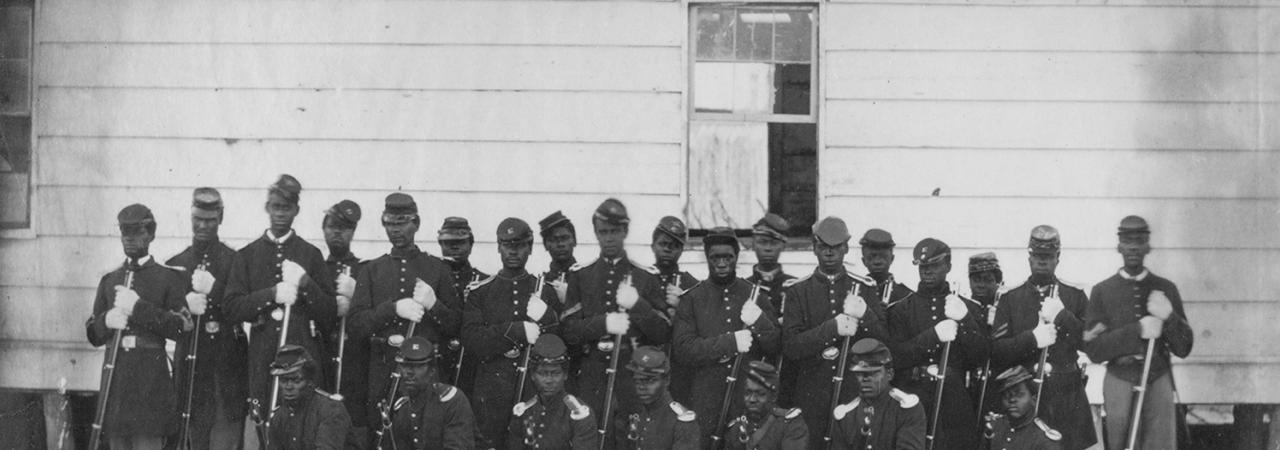

107th Colored Troops (USA), Ft. Woodbury, Arlington County, Virginia, Nov. 1, 1865.

Jefferson Davis told the Confederate legislature in January 1863 that the Emancipation Proclamation was “an authentic statement by the Government of the United States of its inability to subjugate the South by force of arms.” Indeed, the Emancipation Proclamation was a war measure deemed necessary in order to preserve the Union. In the proclamation, President Abraham Lincoln wrote that it was “a fit and necessary war measure for suppressing said rebellion.” He also ordered his field commanders to receive men of African descent into all armed services of the United States. This order resulted in the organization and deployment of United States Colored Troops as an “indispensable means” to preserve the Union.

Though African Americans were serving in the Federal navy when the war began, it was not legal for them to serve in the Federal army. Congress gave the president the authority to bring men of African descent into the army in July 1862 via the Militia Act of 1862. In a separate piece of legislation passed and signed into law that same month, Congress gave men of African descent motivation to fight by declaring free the slaves of supporters of the rebellion.

The chief executive’s vehicle for implementing and enforcing both of these pieces of legislation was the Emancipation Proclamation, a draft of which he presented to his cabinet on July 22, 1862, five days after signing them into law. Secretary of Treasury Salmon P. Chase advised him to add stronger language concerning the arming of men of African descent, while Secretary of State William Seward advised the president to wait for a military success before issuing it. Calling the proclamation a practical war measure, Lincoln waited for a victory while his War Department quietly began organizing colored troops.

Nine days after the July cabinet meeting, Chase wrote to Maj. Gen. Benjamin F. Butler, the commander of the Department of the Gulf headquartered in New Orleans, informing Butler that the President had suggested “it may possibly become necessary, in order to keep the [Mississippi] river open below Memphis, to convert the heavy black population of its banks into defenders.” Chase encouraged Butler to call “colored soldiers to the defense of the Union,” ensuring him that the president would sanction such an action. On September 27, 1862, Butler mustered into service the first African-descent regiment officially brought into the Union army, the 1st Louisiana Native Guards, later redesignated as the 73rd United States Colored Infantry (USCI). Butler also commissioned 30 men of African descent as officers to command the regiment on the company level.

“Better soldiers never shouldered a musket,” Butler exclaimed. Impressed by how quickly they mastered drill movements, he wrote: “I observed a very remarkable trait about them. They learned to handle arms and to march more easily than intelligent white men. My drillmaster could teach a regiment of Negroes that much of the art of war sooner than he could have taught the same number of students from Harvard or Yale.” These soldiers demonstrated their skill and bravery in an assault on Port Hudson on May 27, 1863.

In August 1862, Secretary of War Edwin Stanton ordered Brig. Gen. Rufus Saxton to organize colored troops in South Carolina. Earlier that spring, Maj. Gen. David Hunter had illegally organized a South Carolina regiment comprised of “fugitive slaves” and was ordered to disband the unit. Reorganized that summer under orders of the War Department, three companies of the 1st South Carolina Infantry (African Descent) — later redesignated as the 33rd USCI — were conducting raids along the coast of Georgia and Florida before year’s end. Due to familiarity with the terrain, their unconventional operations were very successful.

Col. Thomas W. Higginson, the first commander of this South Carolina regiment, wrote, “We, their officers, did not go there to teach lessons, but to receive them. There were more than a hundred men in the ranks who had voluntarily met more dangers in their escape from slavery than any of my young captains had incurred in all their lives.”

Lincoln claimed victory after the Battle of Antietam and issued the Preliminary Emancipation Proclamation five days later on September 22, 1862. Frederick Douglass wrote in the October edition of his Monthly that, in order for the Emancipation Proclamation to free any slaves, two conditions had to be met.“ The first is that the slave States shall be in rebellion as of January 1, 1863, and the second is that we must have the ability to put down the rebellion.” With this understanding, thousands of African Americans enlisted in the Federal army and navy before the final proclamation was issued on January 1, 1863.

Five African-descent regiments were organized, trained and conducting combat operations before January 1863. Four were organized in Union-occupied territories in the South, Louisiana and South Carolina. Though mostly made up of Southerners, the 1st Kansas Colored Infantry, which was later redesignated as the 79th USCI, was the first regiment organized in the North. Before gaining Federal recognition, this regiment engaged Confederate forces in a skirmish near Butler, Missouri, on October 29, 1862, and was victorious.

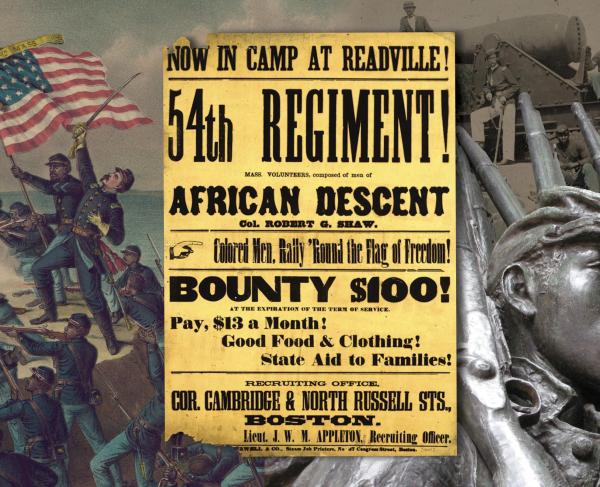

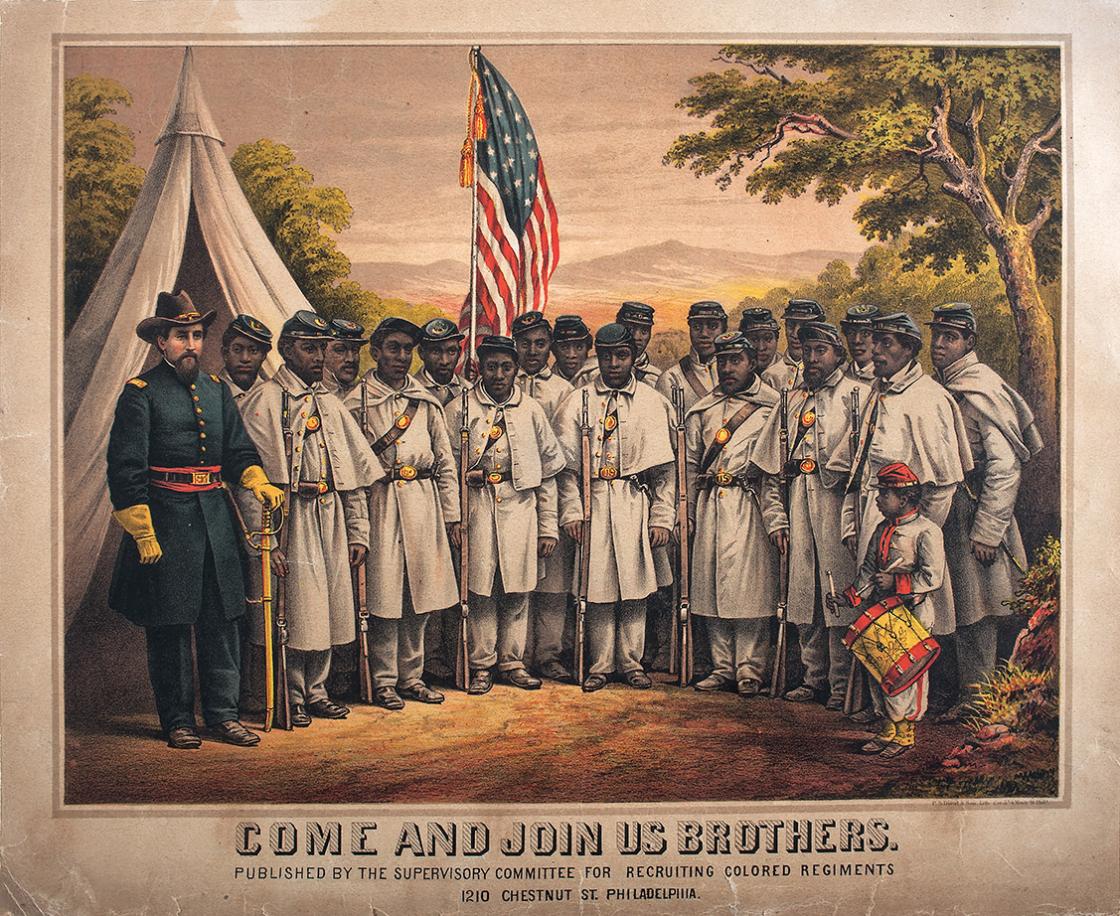

On January 26, 1863, Secretary of War Edwin Stanton gave Massachusetts Governor John Andrew authorization to raise volunteers that “may include persons of African descent.” The first such regiment organized by Andrew was the 54th Massachusetts Infantry. Andrew offered the colonelcy of the regiment to Capt. Robert Gould Shaw, scion of a prominent abolitionist family, then a company commander with the 2nd Massachusetts Infantry serving in the Virginia Theater. Shaw was initially reluctant to accept the offer, in part because of a proclamation issued by Confederate President Jefferson Davis in December 1862 effectively ordering the execution of officers commanding “negro troops.” Overcoming his reservations, Shaw telegraphed Andrew to accept the commission in early February 1863.

The regiment was trained at Camp Meigs in Readville, Mass. “Immediately upon arrival here on Wednesday afternoon,” wrote Corporal James Henry Gooding, “we marched to the barracks, where we found a nice warm fire and good supper in readiness for us. During the evening the men were supplied with uniforms, and they are now looking quite like soldiers.”

By early March, 150 men were in camp, and Shaw was surprised by their military competence. “There are several among them,” he wrote, “who have been well drilled, & who are acting sergeants. They drill their squads with a great deal of snap, and I think we shall have good soldiers.” The regiment’s lead drill sergeant and original sergeant major was Lewis Douglass, Frederick Douglass’s eldest son.

President Lincoln placed a priority on organizing colored troops. He wrote a letter to Maj. Gen. John Dix in January 1863, encouraging him to organize colored troops along the Virginia Peninsula. In a March 1863 letter to Maj. Gen. Nathaniel Banks, then the commander of the Department of the Gulf, Lincoln pointed out that “this element of force is very important, if not indispensable.” The president informed Banks that he had sent David Ullmann “with a commission of a Brigadier General, and two or three hundred other gentlemen as officers” to Bank’s department “for the purpose of raising a colored brigade.”

To prevent officers who opposed the enlistment of African-descent soldiers from impeding the recruiting effort, Lincoln sent the Adjutant General of the Army Brig. Gen. Lorenzo Thomas to the Mississippi Valley to supervise the effort that spring. By the end of May, five African-descent regiments — three from Louisiana, one from Mississippi and one from Arkansas — were organized into Ullmann’s African Brigade and assigned duties at Milliken’s Bend and Lake Providence, La., to help support Maj. Gen. Ulysses S. Grant’s Vicksburg Campaign. In the Battle of Milliken’s Bend, fought June 6–7, 1863, the brigade defeated a larger Confederate force attempting to defend the besieged Vicksburg. Grant was impressed with their fighting abilities.

Lincoln wrote a letter to Andrew Johnson, the military governor of Tennessee, in March 1863, which encouraged him to raise “a negro military force.” Lincoln emphasized the importance of such a force declaring, “The bare sight of fifty thousand armed and drilled black soldiers upon the banks of the Mississippi, would end the rebellion at once.”

The Bureau of United States Colored Troops was established as a separate office within the War Department on May 22, 1863. Maj. Charles W. Foster was appointed the bureau chief, with the title assistant adjutant general. African-descent regiments organized before the new bureau was established were not the first regiments mustered into the Bureau of United States Colored Troops. Most would retain their state designation until 1864, when they would be designated United States Colored Troops. In June 1863, the first regiment was officially mustered into the Bureau of United States Colored Troops. Organized in Washington, D.C., the regiment was designated the 1st United States Colored Infantry.

That same month, the secretary of war published the department policy on the pay of “colored troops.” In accordance with section 15 of the Militia Act of 1862, the secretary ordered that the regular pay for colored troops be reduced to $10 per month regardless of rank, with $3 deducted for their uniforms. Until the Bureau of United States Colored Troops was established, Lincoln’s War Department had not enforced this congressional mandate.

The pay issue did not materially hamper recruiting efforts, because many African Americans were eager to seize the opportunity to strike a blow for liberty. Corp. John Payne, of the 55th Massachusetts Infantry, wrote,

I am not willing to fight for this Government for money alone. Give me my rights, the rights that this Government owes me, the same rights that the white man has. I would be willing to fight three years for this Government without one cent of the mighty dollar. Then I would have something to fight for.… Liberty is what I am struggling for; and what pulse does not beat high at the very mention of the name?

Throughout the summer of 1863, Lincoln continued to push for the enlistment of men of African descent in the Mississippi Valley. He wrote to Secretary of War Stanton in July 1863,

I desire that a renewed and vigorous effort be made to raise colored forces, along the shores of the [Mississippi] river.” He instructed Stanton to again assign Thomas to this duty, because he was “one of the best (if not the very best) instruments for this service.

Lincoln wrote to Grant in early August 1863 asserting that he believed African-descent soldiers were “a resource which if vigourously [sic] applied now, will soon close the contest.” Grant replied that he shared the president’s belief declaring “by arming the negro, we have added a powerful ally.” Grant also informed the president that Vicksburg could not have been captured when it was without the help of African-descent soldiers.

Lincoln defended his emancipation policy and the deployment of colored troops in a letter to a political supporter who doubted the prudence of the policy. “I know, as fully as one can know the opinions of others,” Lincoln wrote, “that some of the commanders of our armies in the field, who have given us our most important successes, believe the emancipation policy, and the use of colored troops, constitute the heaviest blow yet dealt to the rebellion; and that at least one of those important successes could not have been achieved when it was but for the aid of black soldiers. Among the commanders holding these views are some who have never had any affinity with what is called abolitionism, or with Republican party politics, but who hold them purely as military opinion.”

In August 1863, Lincoln informed Union men who expressed reservations about fighting to free the “Negroes” that he had “issued the Proclamation on purpose to aid [them] in saving the Union.” Lincoln also explained that men of African descent were like other men and needed motivation to fight. He argued that the Emancipation Proclamation gave them such motivation. With this motivation, African-descent soldiers became powerful allies to the Union cause, serving in a myriad of combat and combat-related duties. They conducted raids, went on scouting patrols, guarded railroads and communication lines, garrisoned forts in rebel states, conducted assaults, built fortification, laid railroad tracks, and were among the most capable spies in the war.

The best African-descent spies and recruiters were provided by a secret African American organization Allan Pinkerton referred to as the “Loyal League.” One of the leaders of this organization, Martin Delany, wrote to the War Department in 1863, informing Secretary Stanton of the reach of the organization. “We are able, sir,” wrote Delany, “to command all the effective black men, as agents, in the United States.” This secret organization was a valuable asset to the Union cause, and Lincoln commissioned Delany a major of infantry in February 1865.

In the president’s annual message to Congress in December 1863, Lincoln reported that his emancipation policy and the deployment of colored troops had given new hope as to the future of the conflict. He said, “Thousands recently slaves now bear arms for the Union; thus giving the double advantage of taking so much labor from the insurgent cause, and supplying the places which otherwise must be filled with so many white soldiers. So far as tested, it is difficult to say they are not as good soldiers as any.” As evidence of the success of his policy, he noted that “rebel borders are pressed still further back and by the complete opening of the Mississippi, the country dominated by the rebellion, is divided into distinct parts, with no practical communication between them.”

In the annual War Department report submitted that December, Stanton reported that it was now evident that African-descent soldiers made good infantrymen, artillerymen and cavalrymen. He declared, “[T]he slave has proved his manhood and his capacity as an infantry soldier at Milliken’s Bend, at the assault upon Port Hudson and the storming of Fort Wagner.” Stanton went on to state that the “qualifications of the colored man for artillery service [had] long been known and recognized by the naval service,” and he cited an official report on the combat actions of “30 men of Company A, First Mississippi regiment of cavalry (African)” as evidence that he made a good cavalryman as well. Lincoln’s War Department clearly argued that these soldiers were valuable operational assets to the Union army and was fully committed to an emancipation policy that included the deployment of colored troops in all combat related activities.

United States Colored Troops played a noteworthy role in every major campaign in the later stages of the war. During Maj. Gen. William T. Sherman’s Atlanta Campaign, they served as scouts and pioneers and guarded the rail lines that were critical in supplying the army. Sherman wrote that “the great question of the campaign was one of supplies” and United States Colored Troops were instrumental in ensuring that it was answered. In the Petersburg and Richmond Campaign, 15 African-descent soldiers earned the Medal of Honor. Colored troops in the Army of James captured Confederate positions along the New Market Heights Road in the fall of 1864, thus occupied the closest positions to Richmond in early 1865. According to Chaplain Garland White of the 28th USCI, once enslaved in Virginia, “the colored soldiers of the army of the James were the first to enter the city of Richmond” on April 3, 1865. On April 9, the 41st USCI played a key role in a final skirmish near Appomattox Court House, just hours before Robert E. Lee’s surrender.

On battlefields in the East and West, African-descent soldiers demonstrated that they could and would fight well, capturing and occupying a portion of every state in rebellion by the end of 1864. Maj. Gen. George Thomas, commander of the Army of the Cumberland declared after the Union victory at the Battle of Nashville in December 1864, “Gentlemen, the question is settled, the negro will fight.” Governor Henry Allen of Louisiana wrote in late 1864 in an attempt to convince the Confederate War Department to enlist the Negro, “We have learned from dear brought experience that the negro can be taught to fight.”

Indeed, Lincoln’s emancipation policy and the deployment of United States Colored Troops added a powerful ally to the Union and contributed significantly to the ability of government forces “to subjugate the South by force of arms.”

Related Battles

5,000

7,208