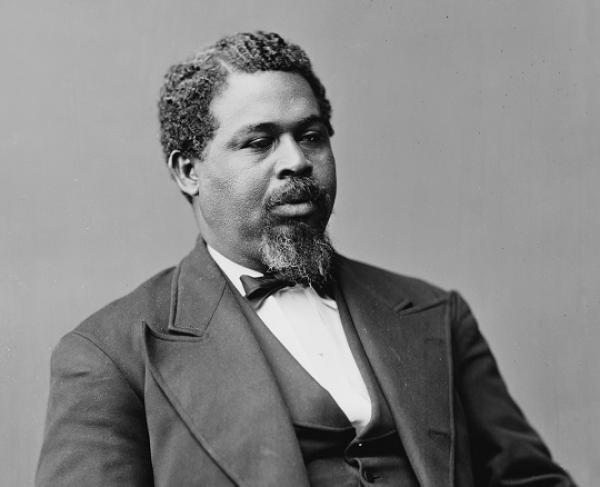

Robert Smalls

Robert Smalls did something unimaginable: In the midst of the Civil War, this black male slave commandeered a Confederate ship and delivered its 16 black men, women and children passengers from slavery to freedom. From slave to sailor to Congressman, read on for more about this extraordinary person.

Robert Smalls was born into slavery in Beaufort, South Carolina on April 5, 1839. His mother, Lydia Polite, was a slave owned by Henry McKee, who may have been Smalls’ father. Robert’s mother had grown up in the fields, and while he now worked in the house with her, she feared Robert would grow up without knowing the plight of the slaves forced to work in the fields on the plantation. She showed him the full horrors of slavery, making him witness the whippings of the field hands which were a frequent occurrence. After seeing the brutality of slavery, Robert grew defiant and frequently found himself in the Beaufort jail. His mother feared for his safety, so she arranged with McKee to send Robert to Charleston where he would work as a laborer. At the age of 12, Smalls made one dollar a week, with the rest of his wage sent back to his master.

Smalls worked many jobs, mostly in and around Charleston Harbor. On December 24, 1856, Robert married Hannah Jones, an enslaved hotel maid. With their owner’s permission, they moved in together and had two children, Elizabeth, and Robert Jr. Smalls saved money and attempted to buy the freedom of his new family, but Hannah’s owner demanded 800 dollars for her freedom. Robert knew as long as he and his family were in chains, they could not be sure of a future together, and it would have taken him years to save enough money. Smalls promised his wife they would one day escape from slavery.

After the war broke out, Robert was assigned to the Planter, a Confederate military cargo transport. Smalls piloted the Planter around Charleston harbor, gaining the confidence and trust of the black crew members and the three white officers. Knowing the crew trusted him, Smalls devised a plan of escape. One night when the officers left to sleep ashore, Smalls and the crew took the ship. Smalls piloted the ship out of the harbor and surrendered the Planter and its cargo to the Union Navy. He also volunteered his knowledge of Charleston’s defenses, leading to the capture of Coles Island a week after his escape. Rear Admiral Samuel Francis Du Pont wrote that Robert “is superior to any who have come into our lines — intelligent as many of them have been.”

The people of the North celebrated Smalls and his crew. Congress awarded them half of the value of the Planter as prize money. Smalls traveled to Washington to meet with President Abraham Lincoln, where he helped to persuade Lincoln to permit black men to serve for the Union army. Soon after the meeting, Secretary of War Edwin Stanton ordered 5,000 former slaves to fight for the Union. Afterward, Smalls became the pilot of a Union ship, the USS Crusader, and later captain of the Planter. He became the first black man to be promoted to captain, although he was never a commissioned officer. In 1897, by an act of Congress, Smalls was granted a pension equal to that of Navy captain.

After the war, Smalls returned to his native Beaufort. He bought his former master’s home, seized earlier by Union tax authorities. In 1868, Smalls was elected to the South Carolina House of Representative and later to the South Carolina Senate. In 1874, Smalls was elected to the U.S. House of Representatives. As a member of Congress, he fought against the disenfranchisement of black voters across the South. He represented South Carolina’s Fifth Congressional District from 1875 to 1879 and from 1882 to 1883. Smalls served South Carolina’s Seventh Congressional District from 1884 to 1887. In the 1890s, he was offered a U.S. Army colonel’s commission in the Spanish-American War and the post of U.S. Minister to Liberia, but he turned down both offers.

Robert Smalls died of malaria and diabetes in 1915. He had witnessed slavery, emancipation, the right of African American men to vote and serve in the ranks of the U.S. government. W.E.B. Dubois said on the history of freedom that, “The slave went free; stood for a brief moment in the sun; then moved back again toward slavery.” Smalls was lucky to live in that moment in the sun. He died as the South worked to recreate slavery through the Black Codes and Jim Crow laws. Despite this, Smalls refused to engage in pessimism, telling the South Carolina legislature:

“My race needs no special defense, for the past history of them in this country proves them to be the equal of any people anywhere. All they need is an equal chance in the battle of life.”