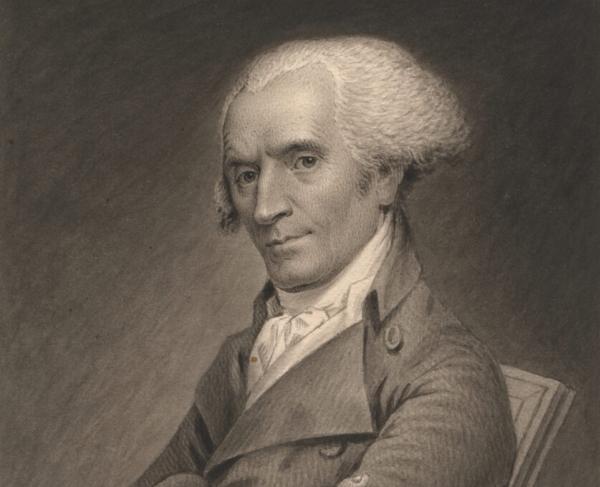

Charles “No Flint” Grey

A man from a prestigious family and a collector of even more prestigious titles, General Charles Grey came to be associated with some of the more controversial and sordid events of the Revolutionary War.

The son of a prominent Northumberland baronet, Charles Grey was born in his family’s estate in Howick, a small village lorded over by the Greys since the 13th century. Very little is known about his childhood and education, apart from the fact that he had two older brothers who eventually died without issue. The few sources we do have do not note anything unusual outside the life of a young gentleman, however. Not expecting to inherit his father’s property, Grey began a military career in 1744 when his father purchased a commission for him at the start of the War of Austrian Succession and concurrent Jacobite rebellion. He also saw action in the Seven Years War a decade later, fighting in Germany, France, Havana and Portugal. Both the Austrian Succession and Seven Years Wars left a great impression on him, giving him many opportunities for a kind of on-the-job-training as he formed close connections to several senior officers happy to mentor him, such as the famous James Wolfe, William Petty, the Earl of Shelburne, and Prince Ferdinand of Brunswick-Wolfenbüttel, who kept the young Grey as his aide-de-camp for a time. One of his most formative experiences while on the Prince’s staff was the Battle of Minden in the modern German state of North-Rhine Westphalia, where he saw a single line of British and Hanoverian troops withstand a French cavalry charge, then immediately countercharge the entrenched French infantry, sweeping them from the field. The battle taught Grey a valuable lesson in the importance of both troop discipline and the value of shock combat. Another formative experience during the war came in 1762, not on the battlefield, but in the wedding chapel as he married Ms. Elizabeth Grey of Southwick in West Sussex. The marriage proved both happy and fruitful, lasting until 1807 and producing eight children. After the war’s conclusion, Grey briefly retired from the army, but still took up administrative posts, including a position as aide-de-camp for King George III.

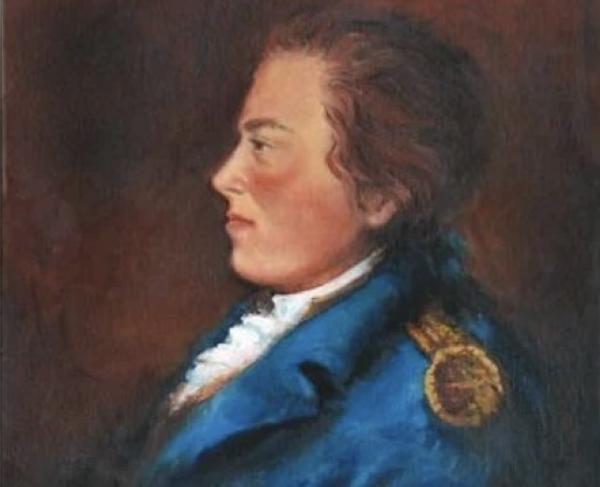

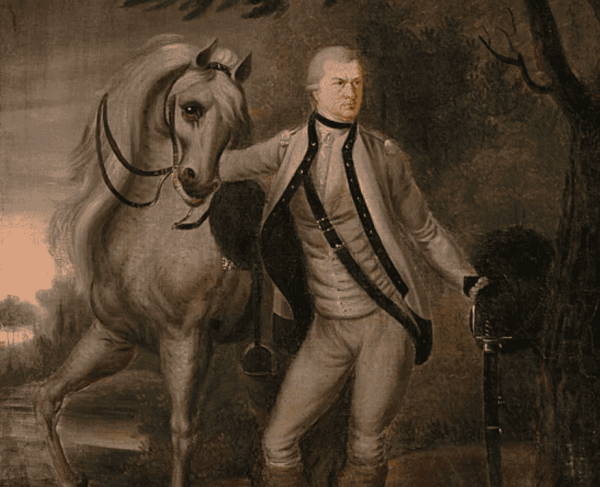

Grey reentered the military on the outbreak of the War for Independence, arriving in 1777 after receiving a promotion to full colonel, but by the time of the Battle of Brandywine on September 11th, 1777 he had become a major general commanding the Third Brigade of William Howe’s army. His most famous action, however, came only a few days after Brandywine, the Battle of Paoli, or as many Americans at the time called it, the Paoli Massacre. Commanding a few regiments of foot, Grey encountered a detachment from the Continental Army under General Anthony Wayne on a supply run not far from where Wayne grew up. Despite the Americans outnumbering him almost two to one, Grey remembered the lesson he learned at Minden and advanced against the Continentals in the dead of night and under the cover of darkness. As an extra precaution, Grey ordered his troops to remove all flints from their muskets, preventing them from firing, as a powder flash would give away their position, but not from performing a bayonet charge. The plan worked flawlessly, as Grey’s disciplined and experienced redcoats caught Wayne’s haphazardly equipped soldiers off guard and easily smashed through them. His bayonet charge was one of the most well executed tactical maneuvers of the entire war, and his decision to remove his troops’ flints gave him his nickname “No Flint” Grey. The Americans, however, claimed that British troops murdered unarmed prisoners and labelled the engagement a massacre, though evidence for that is sparse. He saw action again at Germantown and Monmouth and spent much of 1778 conducting raids on various undefended rebel towns, before courting controversy again at the “Baylor Massacre,” where he used similar tactics to those at Paoli to similar effect on a Continental garrison near Tappan, New York. Whatever may have happened under Grey’s command in North America, such controversies did nothing to affect his reputation in Britain. After his recall to England in 1778, King George granted Grey a knighthood in the Order of the Bath as well as a promotion in Lieutenant General.

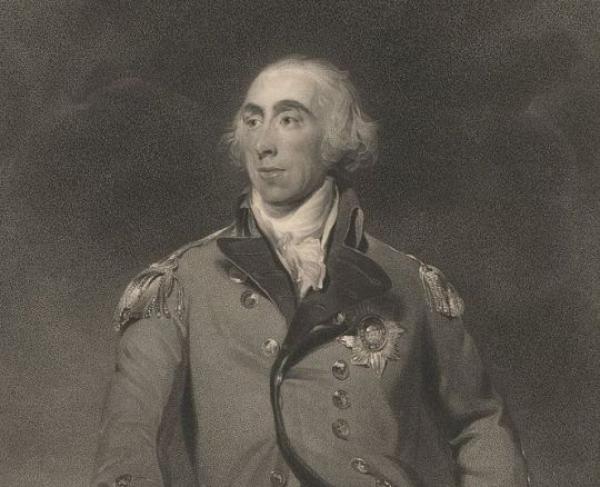

After the war, Grey once again entered a period of half-retirement and working with architect William Newton to build his new home of Howick Hall, which replaced the medieval tower house he was born in and still stands to this day. But like the last time he left military life, this reprieve did not last. A decade after the end of the war with America, Great Britain declared war on the nascent French Republic to halt the spread of revolutionary thought in Europe. At first chance, Grey rejoined the army and took part in the fighting in Belgium and the Caribbean, occupying several important French plantation colonies. This, however, was some of the last action he ever saw personally, as in 1797, he took a new position as Governor of Guernsey, one of several small islands in the English Channel. This did not stop the flow of honors and titles placed upon him for his service. In 1801, the King raised Grey to the Peerage and granted him “the Dignity of a Baron of the United Kingdom…by the Name, Stile (sic), and Title of Baron Grey, of Howick,” as reported by the London Gazette. Five years later, he further honored Grey by making him the 1st Earl Grey and Viscount Howick. Grey served as Governor of Guernsey until his death in 1807, which passed his estate and many titles onto his eldest son, Charles Grey, the 2nd Earl Grey, who later became Prime Minister of the United Kingdom, passed the 1832 Reform Act which greatly democratized the House of Commons, abolished slavery in the British Empire, and even gave his name to a popular variety of tea.