The Battle of Paoli: "Massacre" or Decisive British Victory?

Situated between the battles of Brandywine and Germantown were two engagements that signified the confusion and bitter reality of the Philadelphia campaign. The Battle of the Clouds (or White Horse Tavern) on September 16, 1777, and the Battle of Paoli on September 20, 1777, were two instances where the historical record, even in the days after they occurred, distorted what actually happened. Some historians have argued this was intentionally done, particularly with Paoli, by patriots determined to demonize the British occupation presence within occupied Philadelphia. Much like the aftermath of what occurred in Boston in March 1770, the “surprise” attack on General Anthony “Mad Anthony” Wayne’s men and the supposed show of no quarter given to the unarmed Americans at Paoli, led to American propaganda labeling it a massacre. Indeed, the Paoli Massacre as it has become known in many circles has taken on a life of its own. What were the events that led to this midnight ambush on September 20, 1777? Was it really a massacre? And what were the effects that reverberated between both armies and the surrounding civilians in the region?

The Philadelphia Campaign had started off with waves of optimism among the ranks of General George Washington’s Continental Army. The previous spring had been a war of attrition in the northern hills of New Jersey, pitting a nearly beaten — but recently victorious — American force against an ever—frustrated British army under generals William Howe and Lord Charles Cornwallis. Washington had to maintain a level of deception for his army’s survival, avoiding any direct engagement, despite several attempts by the British to draw them out of their secluded positions in Watchung.

Running out of patience by June, Howe decided that the road to Philadelphia – the rebel capital and his newly decided objective — would have to come by sea instead of traversing through the dangerous New Jersey countryside. The British departed Staten Island on June 30 and made way for the Chesapeake Bay. Howe’s plan was to make landfall at Head of Elk in Maryland and then march northward to Philadelphia, about 51 miles away. Washington had known for months of Howe’s conviction that capturing Philadelphia would strike a pivotal blow against the rebels. Howe, though, was overconfident in the psychological effect the rebel capital’s fall would have on the rebellion. Washington, sensing this, was determined to defend Philadelphia, but was not convinced it would dramatically alter the war if it were fall to the British.

Washington’s army made their stand at Chadds Ford, Pennsylvania, along the banks of Brandywine Creek. The Continental Army had significantly rebounded since the winter months and held a strength of between 14-15,000 soldiers. In comparison, Howe had between 15-16,000 soldiers. This was the largest assembly of armed troops in a single battle during the war. Washington had the advantage in holding the eastern and northern banks of the Brandywine, as the creek slowed the British advance. However, American scouts had fatally miscalculated their northern flank, thinking their lines stretched far enough to cover all of the fords along the creek. They were wrong. Howe spied this flaw and split his army in two. Half the British army attacked from the center, engaging the bulk of Washington’s forces, while Howe maneuvered the other half around the American northern flank, finding an unoccupied ford, he swung southward against the unknowing American Army. It was virtually the same tactic used by Howe against Washington on Long Island in August 1776, and that had proven nearly fatal.

Once again, the Americans were completely caught off guard. Whatever advantages the Continental army held quickly evaporated as portions of the American line swung northward to beat off the flanking British regulars. Generals John Sullivan, Adam Stephen, and Lord Stirling led their divisions to head off this rout, allowing the main body of the American army to fall back and preserving Washington’s army from total destruction. They were fortunate; the British only captured or killed about twelve hundred soldiers and seized most of the American cannon and artillery pieces.

Five days later, still reeling from another missed opportunity, Gen. Howe positioned himself to engage the Continental army just west of the Schuylkill River in southeastern Pennsylvania, learning that the Americans were restocking their supplies at their depot at Reading. Initially, the Americans moved to Germantown, but Washington became concerned that Reading was exposed to possible British plunder, and moved to reinforce it. Having been tipped off that Washington was now moving west, Howe decided to meet the Americans in another major engagement. But even the best laid plans do not always survive contact with chance. Just as the battle near the White Horse Tavern began to take shape, the skies opened up. Swirling winds and torrential downpours essentially made all flintlock muskets useless. Wary of a bayonet attack by the British, and seeing the soggy ground turn to mud, Washington abruptly ordered a retreat. Some historians have maintained that had the weather not interfered, the Americans may have been able to recapture their losses at Brandywine. But there is no evidence to suggest how the battle would have turned out one way or the other.

Following the general retreat of the Continental army back over the Schuylkill, Washington ordered Anthony Wayne’s mixed Pennsylvania Division of infantry, artillery, and cavalry to remain on the western side of the river to prod and harass the British rear. Wayne would also serve as the first line of defense if the British decided to move on Philadelphia. Because of the storm and the conditions of the roads in the days that followed, Howe and the British army had no real intentions of making a major move. However, when Wayne’s position was detected by British scouts on September 19, Howe gave orders to attack the lone American division.

What transpired on Saturday evening, September 20, has long been contested as either a skirmish or a full engagement; one of bravery or one of cowardice; an anticipated attack or a surprise massacre. Eye-witness accounts give conflicting narratives to the actual events. Historians have struggled to sift through the available documents to paint an accurate portrayal. Perhaps the best work is by historian Thomas H. McGuire. What we know for certain is that Gen. Wayne knew that Howe was likely going to target his lone division near the Paoli Tavern. It is unclear though if Wayne himself knew how pending this likely attack was. McGuire does a great job of piecing together the testimonies of Wayne’s subordinates, which indicate a breakdown in communication somewhere in the chain of command. Whatever intelligence reports Wayne had been privy to, there is evidence that he had not received other reports that might have reinforced the urgency in preparing for an attack.

Wayne grew up within earshot of Paoli Tavern and was expected to use his local knowledge to his advantage. But complicating matters for Wayne was the fact that this part of Pennsylvania was a mix of citizens loyal to the Patriot cause and citizens loyal to the crown. Because of this, Grey’s soldiers were as well informed about the enemy dispositions, as Wayne was about what his adversary was planning. It was Grey, though, who seemed to take advantage of the intelligence gained. Compounding matters more, Wayne was under the impression that General William Smallwood’s forces were close enough to reinforce his division at any moment. It was this belief that kept Wayne from relocating his position, even with the knowledge that Howe’s troops likely knew his location. As McGuire posits, because of these failures, the Continentals under Wayne’s command knew they were in imminent danger of an attack but could not decide on how to prepare for it.

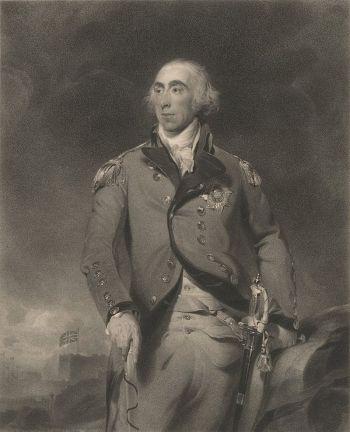

The Americans built makeshift huts and ammunition ‘booths’ to prevent vital supplies from the continuously unstable weather pattern. They started campfires and Wayne posted several pickets on his flanks to patrol the outer perimeter of the encampment. His division consisted of about 1,500 soldiers and militia. Howe had dispatched General Charles Grey with the 42nd and 44th Regiments of Foot, along with a light troop of the 2nd Infantry. They were to rendezvous with Col. Thomas Musgrave and the 40th and 45th Regiments of Foot on their approach, totaling about 5,000 British soldiers. A Captain John André, later the major who acted as the British Army’s liaison to turncoat American general Benedict Arnold, accompanied this patrol. Grey gave the order to remove all flints from their muskets, and to fix their bayonets. The plan was key to what was about to unfold: no British trooper would give away their approach by firing on the Americans. Instead, they’d allow the Americans to fire first, thus revealing the enemy’s position with their flintlock bursts. The British would then storm through the camp with a bayonet charge. Unfortunately for the Continentals under Wayne, this plan proved brilliant in the moment, and was executed spectacularly by Grey’s men.

The British approached from the east near Warren Tavern, eliminating the outer American pickets, and preparing their final assault on the American position. Despite rumors that Wayne’s men were taken by surprise, this is not what happened. In actuality, the Americans saw the British approaching. They proceeded to fire and gather their ranks to form a defensive line of attack. However, the British rushed forward while the Americans reloaded, and bayonets proved to be the deciding element in the close quarters battle that ensued. Other American lines were decimated by the overwhelming British forces. The raging campfires only helped illuminate the Americans as they scattered to safety from the swarming British regulars. Wayne rallied portions of his disintegrating division and proceeded with an exit strategy westward toward the White Horse Tavern, where Gen. Smallwood’s forces were approaching upon hearing the sounds of battle. The retreat by Wayne’s men though sent Smallwood’s forces into a panic, and no order could save the moment.

The Battle of Paoli cost the Americans fifty-three confirmed dead, all to bayonet strikes, with about one hundred more wounded and about 70 taken prisoner. The British only reported four killed and seven wounded, none taken prisoner. For his decisive victory in the assault, British Maj. Gen. Charles Grey received the nickname “No Flint” for his order to attack without firing a single musket. The British bayonet was certainly the key factor in the battle. The Continental Army was poorly stocked with bayonets whereas the British made it a standard issue weapon to their infantry. (Another casualty of the Congress’s inability to properly supply the army). Without access to the proper equipment to counter a charge, American units were often prone to retreat at the very sight of a bayonet charge. This psychological effect had won the British many victories on the battlefield. It wasn’t until the Americans were readily and widely equipped with bayonets of their own that the mystique of the British charge disappeared.

General Anthony Wayne’s reputation suffered in the interim as inquiries were made into his conduct proceeding and command during the attack. A court-martial cleared him of any wrongdoing, and he would continue his climb to redemption in the months and years that followed. However, Paoli served as another stain on the Continental Army and the command of George Washington. First, they had lost the Battle of Brandywine. Then came the near-miss at the Battle of the Clouds. Now there was the Paoli attack. Though local patriots tried to spin the battle as a ‘massacre,’ there is no evidence to indicate the British attacked in a scandalous manner. Indeed, the term was likely used to scandalize the conduct of the British army’s pillaging and plundering of the local countryside, where multiple farms were razed of livestock, and the daughters of farmers were reportedly raped by British troops. Legitimate outrage or not, Gen. Howe took Philadelphia without much a fight. Washington had balked at defending the entry roads to the city in favor of protecting his precious stores at Reading. Howe virtually walked into Philadelphia unscathed.

In October, Washington tried to draw him out at Germantown, but the disastrous turn of events that devolved the American commander in chief’s battle plans into a smoke-filled chaos effectively ended the Philadelphia Campaign of 1777. Howe had taken the rebel capital; the Continental Congress had scattered and was on the run. Loyalist citizens in Philadelphia welcomed the British with open arms, and lavish parties were thrown in Howe’s honor. And George Washington’s depleted army once again limped into winter encampment. Valley Forge would be their home for the ensuing months. It would be a tenure of great trials, and of unlikely rebirths for the young American army.

Feature Reading:

- The Philadelphia Campaign, June 1777-1778 By: David G. Martin

- Battle of Paoli By: Thomas J. McGuire