Listen, my children, and you shall hear

Of the midnight ride of Paul Revere,

On the eighteenth of April, in Seventy-Five:

Hardly a man is now alive

Who remembers that famous day and year.

Part of Paul Revere's Ride by Henry Wadsworth Longfellow

Paul Revere is one of the most iconic heroes of the American Revolution, immortalized by Henry Wadsworth Longfellow in his 1860 poem, Paul Revere’s Ride. Longfellow was writing in a time of growing national crisis, with war clouds forming between North and South, and wrote a poem more about national unity than the true story of Paul Revere. While Longfellow helped immortalize Revere, he also perpetuated some of the most common myths of the famous “Midnight Ride.”

Revere was born January 1, 1735, his father Apollos Rivoire (anglicized to Paul Revere) was a French Huguenot Silversmith, a trade the younger Paul would also take up. As a tradesman, or “Mechanic,” Revere existed in the emergent middle class of Boston society, equally comfortable along the ropewalks as in the social societies frequented by the wealthy. After his father’s death, and a brief service during the French and Indian Wars, Revere inherited his own Silver shop.

When the British economy started to suffer after the French and Indian Wars ended, so too did Boston’s. Increased British regulation in the colonies, beginning with the Stamp Act in 1765, further damaged the local economy. Because of Revere’s trade, including his new dentistry business, and his social standing, he was one of the most well-connected people in Boston, closely associated with many of the personalities that would begin to agitate against Britain.

In 1765, Revere joined the Sons of Liberty. Revere produced many anti-British engravings, including his sensationalized depiction of the Boston Massacre, which circulated widely and helped bolster anti-British sentiments. After the Tea Act, Revere was one of the ringleaders for the Boston Tea Party. Around this time, Revere became a courier for the Committee of Safety, traveling to other colonies with news of occupied Boston.

As a courier, Revere realized the importance of the quick and accurate spread of information. After the Provincial Assembly was dissolved, and Boston occupied in March 1774, Revere and his fellow couriers began meeting at the Green Dragon, a hotspot of anti-British sympathizers. When not carrying messages, the couriers would monitor British movements in occupied Boston, relaying their movements to Patriot leaders.

In September of 1774, this group of messengers and observers were tested when the British seized gunpowder stored in Somerville. By the time the Massachusetts militias had responded, the mission was complete. The Powder Alarm provided a trial run for both sides and showed both the advantages and the deficiencies of the alarm system that Revere helped establish. In March 1775, the outlawed Massachusetts Provincial Congress issued the following resolution, making the alarm system critical to resisting British force:

Whenever the army under command of General Gage, or any part thereof to the number of five hundred, shall march out of the town of Boston, with artillery and baggage, it ought to be deemed a design to carry into execution by force the late acts of Parliament, the attempting of which, by the resolve of the late honourable Continental Congress, ought to be opposed; and therefore the military force of the Province ought to be assembled, and an army of observation immediately formed, to act solely on the defensive so long as it can be justified on the principles of reason and self-preservation.

On April 18, 1775, the British planned yet another search and destroy mission, aimed at removing arms and supplies from the countryside. This time the target was much farther away, the village of Concord, a hotbed of anti-British sentiment and a major supply cache. Anti-British intelligence in Boston quickly alerted Patriot leader Dr. Joseph Warren, who gave the fateful order to send the alarm, lighting the fuse that would start the Revolution.

Warren sent for Revere and William Dawes in the evening on April 18, once the British intention was clear. Revere would take the short, but more dangerous, water route from Boston across the harbor to Charlestown, while Dawes would ride out across Boston Neck. Warren was concerned that John Hancock and Samuel Adams, both staying in Lexington, were the targets of the British foray. Revere had ridden through Lexington earlier in April, carrying messages to the Provincial Congress meeting in Concord, and knew the route well.

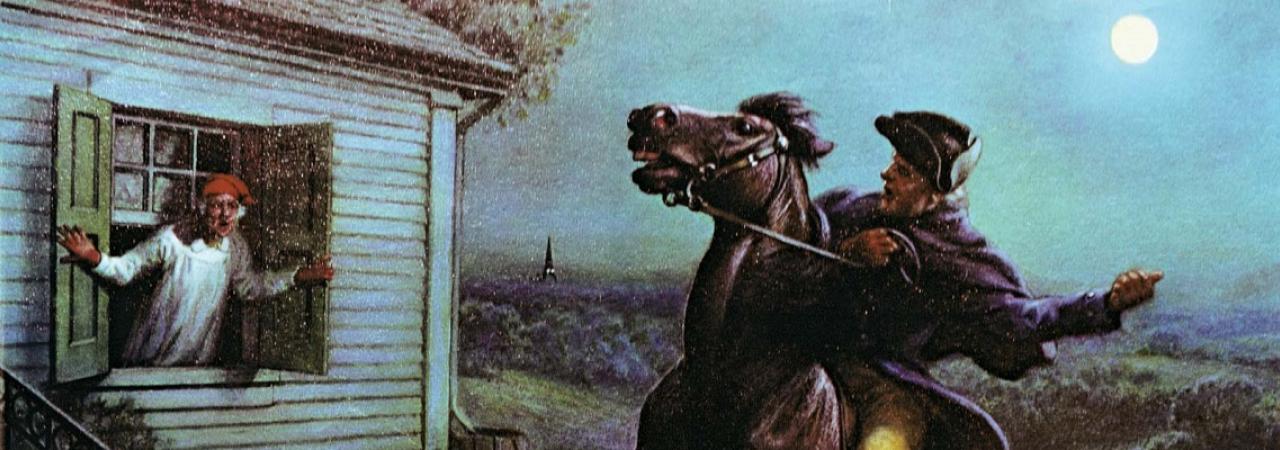

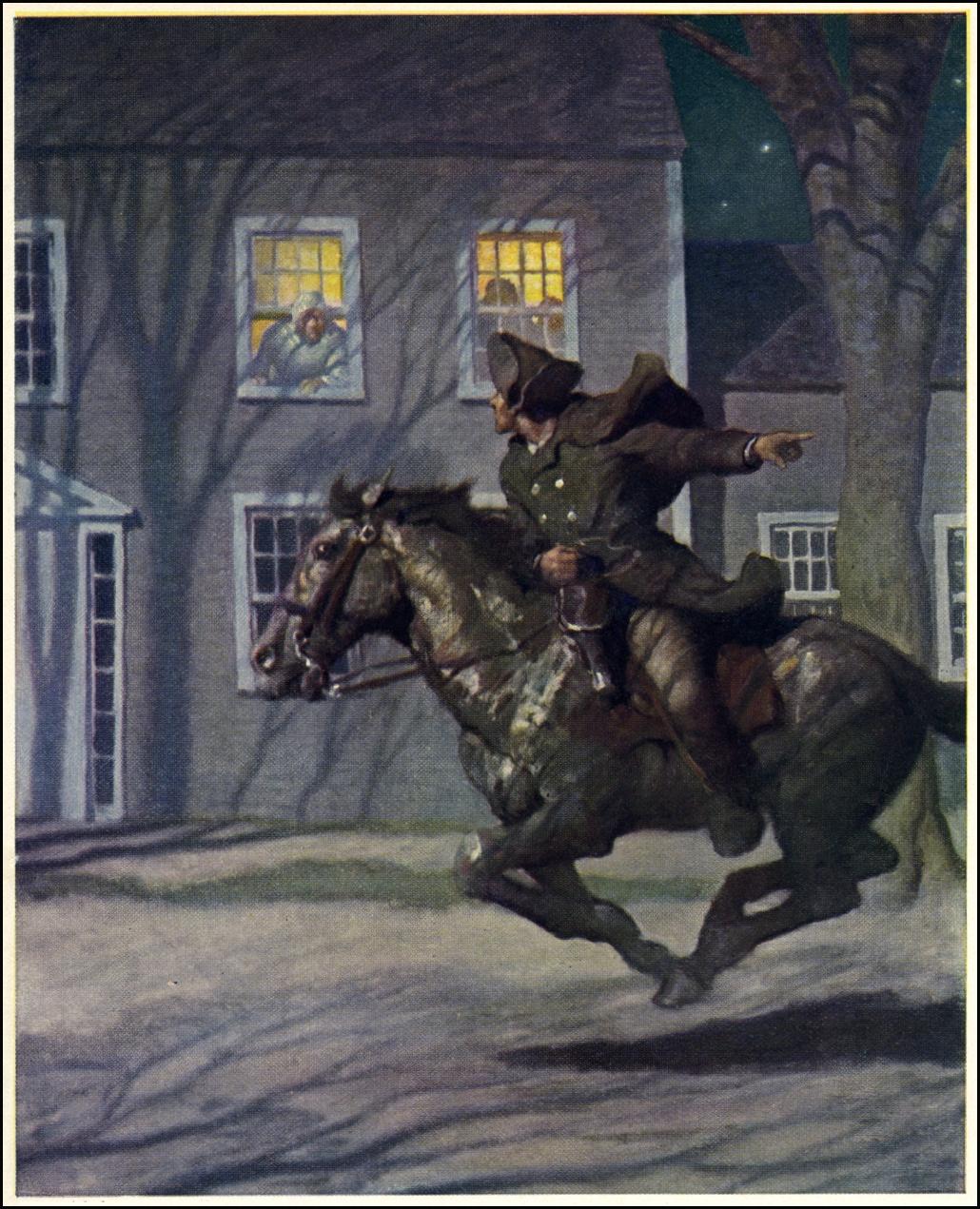

Revere and Dawes departed Boston around 10pm. At the same time, two signal lanterns briefly showed from the Old North Church steeple, a prearranged signal designed by Revere to alert the alarm network across the Harbor. The famous “one if by land, two if by sea” signaled that the British would row across Boston harbor instead of marching out over the neck. Even before Revere landed, the alarm was already spreading across the countryside.

Upon reaching the Charlestown shore, Revere mounted and began his ride to Lexington. Passing through the towns of Somerville, Medford, and Menotomy (Arlington), Revere did not yell “the British are coming!”, instead accounts show that Revere passed the message of “the Regulars are coming out.”

The phrase “the British are coming,” would have been confusing to locals, who still considered themselves British. Everyone knew what “the Regulars are coming out” meant, and as Revere passed through, more alarm riders rode out, signal guns fired, church bells rang, all alerting the countryside to the coming threat. As the alarm spread, Minutemen grabbed their weapons and headed for town greens, followed by the rest of the Militia.

By the time the British finished unloading at Cambridge, the alarm had already reached Concord; Revere’s network had worked splendidly. As the British column moved out, they could hear the signals sounding across the countryside, a foreboding sound heralding a hostile country.

Revere and Dawes met at the town of Menotomy and continued to Lexington to warn Adams and Hancock. After bundling Hancock and Adams out of Lexington, and narrowly missing the vanguard of the British column and its rendezvous with destiny on Lexington Green, Revere and Dawes decided to ride on to Concord. On their way they encountered a young doctor, Samuel Prescott, on his way home to Concord.

Revere’s famous ride ended on the outskirts of Lincoln when he, Dawes, and Prescott ran into a British patrol. While Dawes and Prescott escaped, Revere was captured, playing no further role in the events of April 19. Prescott managed to make it home to Concord, however, and alerted the town. When the British arrived, the men of Concord, Acton, Bedford, and Lincoln were waiting.

While Longfellow mixes myth and reality, his immortal words are still hauntingly accurate:

You know the rest. In the books you have read,

How the British Regulars fired and fled,--

How the farmers gave them ball for ball,

From behind each fence and farmyard-wall,

Chasing the red-coats down the lane,

Then crossing the fields to emerge again

Under the trees at the turn of the road,

And only pausing to fire and load.

Test Your Knowledge

Further Reading:

- Paul Revere's Ride: David Hackett Fischer

- The Revolutionary Paul Revere: Joel Miller

- Firsthand Account of the Midnight Ride: Paul Revere

Related Battles

93

300