The Colonial Responses to the Intolerable Acts

As news of the Boston Tea Party spread across New England, word of similar forms of resistance to the Tea Act were reported across the colonies. Though the Boston Tea Party was the largest and most notable “tea party,” Charleston (then called Charlestown) rebel leaders led by Christopher Gadsen conducted the first “tea party” on December 7, 1773. They illegally unloaded East India Company tea from a docked ship and stored it in the Exchange Building. Though not outright destruction of tea, it was the first colonial physical resistance of East India Company Tea in the colonies.

The reaction to the tea parties in London came strong and swift. Too many times, the colonies had pushed back on British authority. Colonists' rebellious acts were becoming more deliberate; now they had destroyed private property and committed an overt illegal act. In response to the insubordinate actions, Parliament passed a series of laws called the Coercive Acts on March 31, 1774 (called the Intolerable Acts by American colonists). The intent was to punish Massachusetts and set a precedent for Parliament’s authority. When pressed on what these laws would incite in the colonies, Prime Minister Lord North said: “Whatever may be the consequences, we must risk something; if we do not, all is over.”

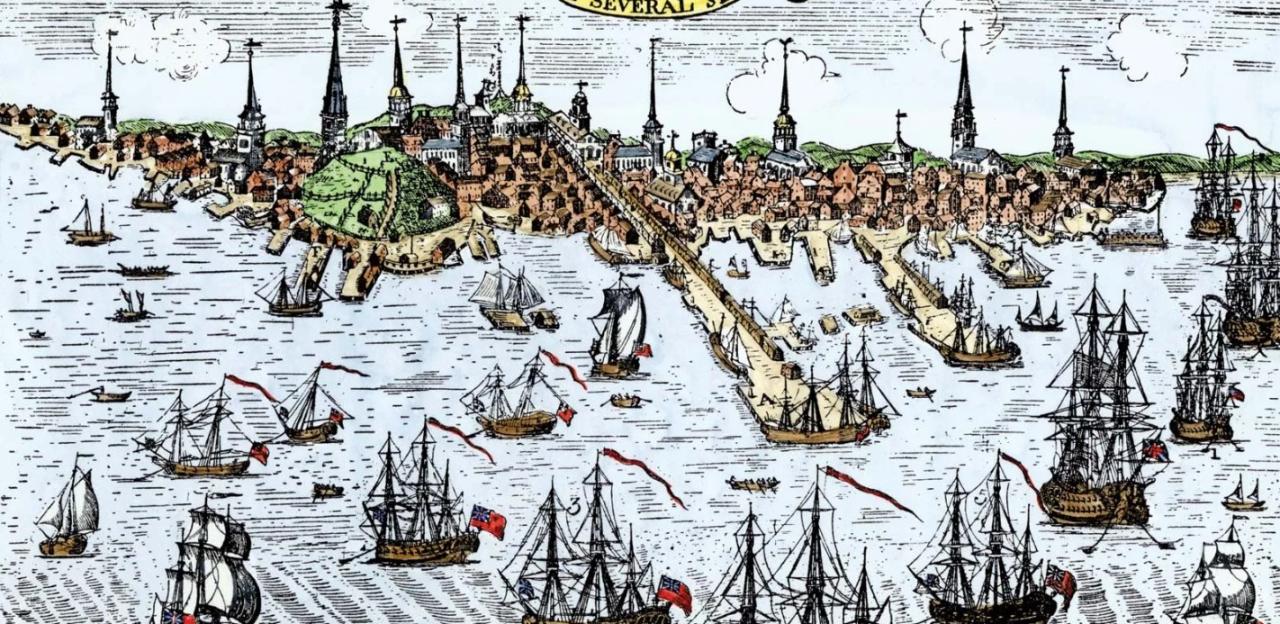

The Coercive Acts included first the closing of the Port of Boston until the damaged tea was paid for and the King believed that order was restored in the colony. To ensure the colony fell back into line, these acts punished everyone in Boston, not just those responsible for destroying the tea. The closed port had a direct economic impact on Boston as the city made its living off of its docks and associated trades. The second act canceled the Massachusetts Bay colonial charter and replaced it with a stricter British government role. The upper house of the state legislature would now be appointed, where before it was an elected body. This act also limited the popular town meetings in Massachusetts to one annual meeting per town. The third part of the Coercive Acts called for any trials against royal officials to be held in Great Britain, not Massachusetts. Colonists believed this would shelter royal officials from proper justice. Royal authorities believed that trials like the one after the Boston Massacre were skewed heavily against them (even though those soldiers were successfully defended). Finally, the last act impacted all of the American colonies. It gave royal officials in the colonies authority to quarter British troops in buildings if the colonial government did not provide suitable housing. Typically, this meant large civic buildings and uninhabited buildings could be put into service for quartering troops. Though many feared this would lead to British soldiers being forced into private homes, at the time of 1774 that was not the case.

The Coercive Acts varied significantly compared to previous British acts that caused discontent in the colonies. This time the acts directly repealed how the colonists ruled themselves, which was rooted in the Massachusetts charter of 1691. This did not just impact those in Boston and coastal cities, but everyone in the colony. From the countryside around Boston, to the western end of the colony, local towns created committees of safety and began to use both political and economic ways to oppose British policies, while simultaneously arming themselves. As British General Thomas Gage wrote: “Affairs here are worse than even in the Time of the Stamp Act, I don’t mean in Boston, for throughout the Country. The New England Provinces, except part of New Hampshire, are I may say in Arms.”

As word reached the other colonies, the response was mixed. Most colonists believed Bostonians should pay for the ruined tea, but they were also overwhelmingly shocked by the harshness of the Coercive Acts. Fearful of England’s new form of authority, support from across the 13 colonies began to pour into Boston. Using an already established “Committee of Correspondence” network created in the early 1770s, colonial leaders began to discuss a proper reaction. Boycotts on imports of British goods and tea especially were accepted broadly.

Colonial governments showed support for Boston through days of fasting and resolutions of support. In Virginia, Governor Dunmore dissolved the Virginia House of Burgesses on May 26 due to their vocal support for Massachusetts and Boston. Many of the burgesses reconvened at the nearby Raleigh Tavern to continue their discussions on how to react to the situation and how they could best fight the Coercive Acts. Local counties in Virginia also began to call out local resolves in support of Boston, Prince William County being one of the first who passed resolves on June 6, 1774, written with George Mason's assistance. Many others across Virginia and other colonies followed. The Coercive Acts were having the opposite intended effect, they were bringing the colonies together in opposition to Royal authority.

Other tea parties also took place in other parts of the colonies. In New York City in April, then Chestertown (Maryland) in May and November in Charleston (South Carolina). None reached the destructiveness of impact of the Boston Tea Party, but each showed the North American colonies were becoming unified against not just the Tea Act but against overarching Royal authority.

The most important response to the Coercive Acts was the creation of the Continental Congress. Twelve colonies (Georgia abstained) sent representatives to the “Congress” in Philadelphia in September 1774. Unlike the previous Stamp Act Congress, the First Continental Congress was attended by the majority of American colonies. The Congress encouraged boycotts and also petitioned the King and Parliament to rescind the Coercive Acts. In response to their planned attendance, Governor Gage dissolved the Massachusetts Provincial Assembly before the Continental Congress met and called for new elections. This did not deter them from sending representatives (John Adams, Samuel Adams, Thomas Cushing, and Robert Treat Paine) to Philadelphia.

Community leaders in Massachusetts began to officially lay out their opposition to the Coercive Acts. One of the most significant were the Suffolk County Resolves, passed in September 1774. These were some of the first and most direct resolves that laid out how to openly oppose the British government. Like other resolves, they called for the boycott of British imports but also supported refusal of paying taxes; called for the creation of a colonial militia; advocated for a colonial government free of Royal authority; called for open disobedience of the closing of the Boston Port; and demanded resignations of all new government appointments. The resolves called for all these measures until the Coercive Acts were repealed. Dr. Joseph Warren took the lead in pushing for the resolves, and Paul Revere personally delivered a copy to the First Continental Congress meeting in Philadelphia.

What began in the harbor in Boston in December 1774 set events at a spiraling pace toward revolution. Each action of defiance by the colonists led the Royal authorities to attempt to tighten their grip. The Coercive Acts did not bring about colonial obedience, rather it led the majority of colonists to support those who looked to martial answers to the problem. The war and independence were just over a year away.