“Boston a Teapot Tonight!”

On December 16, 1773, at the Old South Meeting House, a large crowd of people filled the house of worship, but not for a religious service. Nearly 5,000 people attended the meeting to discuss the city and colony’s response to a new tax on tea and, more directly, the ships in the harbor that held tea from the East India Company. The colonial Whigs did not want the cargo unloaded, but the captains of the ships could not leave the harbor with the tea unless they had approval from the governor. Upon being asked, Governor Thomas Hutchinson said that he did not have the authority to allow the ships to leave without unloading the tea. Adding to that decision, Hutchinson was frustrated with those who had rejected Royal authority over the years. His decision also expressed his disinterest in assisting the Whig cause. Thus, a legal and theoretical standoff ensued. That night, the people of Boston took the matter into their own hands.

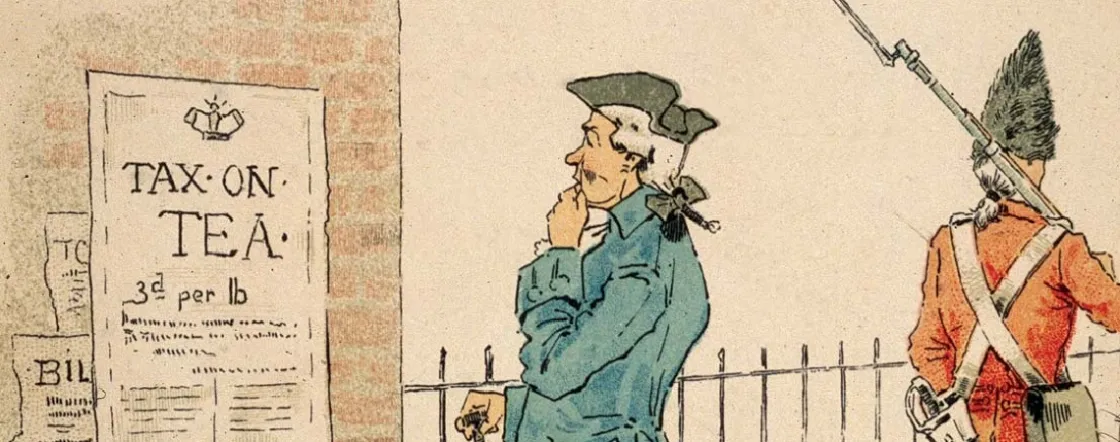

On the surface, the Tea Act of 1773 was rooted in helping pay off the debt of the British Empire, caused in part by fighting the Seven Years’ War (French and Indian War) with France. The Tea Act was one of many Parliamentary laws or “acts” passed to raise revenue in the colonies, which increased payment towards British officials in the colonies, thus making them more loyal to the British Crown. More importantly, the underlying purpose was for Parliament to display its authority to pass laws that were binding in the British colonies. Due to colonial opposition and resistance, many of these acts were repealed. However, the Tea Act sparked an immediate response throughout the colonies.

The Tea Act was also seen as a mode for saving the British-owned business, the British East India Company. Before 1773, the company could only sell its tea in London and was subject to duties. The company had collected large quantities of tea in warehouses in London and was looking for a way to disperse the supply at a bargain. The Tea Act allowed the company to sell directly to American ports without paying the duties. This also restricted American buyers to only purchase their tea from the East India Company, which was subject to a tax. While the price of tea was reduced because the company no longer had to pay the duties in London, Colonists resisted the notion that Parliament could force them to buy tea from the East India Company and strongly opposed the additional tax. Many in Boston made a good living off of smuggling tea from other parts of the globe and this threatened their business.

Though passed in May 1773, the Tea Act did not impact the people in the colonies until fall. Seven ships of tea were sent to four American ports: Boston, New York, Philadelphia and Charleston. Meanwhile, colonial Whig leaders began to organize a resistance to the East India tea that was enroute. In fact, in every other city but Boston, the tea was refused and forced to either be returned to England or confiscated by local officials. In Boston, a determined governor and history of Royal opposition led to a signal event in American history.

On November 28, the ship Dartmouth arrived loaded with tea. British law gave ships with imports 20 days to pay the duties or the local customs officials could confiscate the cargo. Hutchinson, when petitioned, would not allow the ship to leave the port without paying the duty. His sons, who acted as Tea Consignees (authorized to receive the tea and see to its distribution) for Boston, also refused to back down and resign their positions, which had happened in other American ports. Soon, two more ships arrived in the harbor with the unwanted tea. Unable to return the tea to England and without being able to unload it due to the threats of local groups such as the Sons of Liberty, the captains of the ships were in a tight and dangerous spot.

On the night of December 16, one of the largest public meetings in Boston convened at the Old South Meeting House. Speeches by Samuel Adams, John Hancock, Joseph Warren, and other Boston Whig leaders called for the return of tea to England. Later in the evening, word came that a last-minute plea to Governor Hutchinson to let the ships return was refused. Samuel Adams announced publicly: “This meeting can do nothing further to save the country.”

The events that happened next have been debated since 1773. Men arrived outside the Meeting House disguised as Indians (later described as “Mohawks”). Whether or not these men were signaled to move towards the ships with tea is unknown. As the “Mohawks” marched down Milk Street towards Griffin’s Wharf where the three ships of tea were docked, the thousands gathered inside the Old South Meeting House began to pour out of the building. Chants of “Boston a teapot tonight” and “hurrah for Griffin’s Wharf” were reportedly heard. Some people followed the dissenters, others continued to protest in the streets, while still others headed home believing that a confrontation was about to take place.

Many details remain unknown about who exactly the “Mohawks” were that marched on Griffin’s Wharf that night. The men used lamp soot and red ochre to disguise their faces and carried a wide assortment of weapons. As they made their way to the wharf, they yelled and “whooped." Whether or not they had coordinated the timing with leaders in the Old South Meeting House remains unknown. As they made their way to the ships, the Whig leaders inside the Old South Meeting House stayed behind and were never directly part of what happened next.

The men, with a crowd behind them, approached the wharf. There, they divided into three different groups, one for each of the ships: Dartmouth, Beaver, and Eleanor. Being a port city, most of the men knew where to find the cargo they were looking for and how to operate on a ship. Respectfully, most of the other cargo and private property on the ships was not touched. They were only after the tea. Hauling the chests to the deck, they were broken open and dumped into Boston Harbor. Some of the men watched to make sure no one was trying to steal any of the tea that they were dumping. The group of approximately 150 men worked quickly as the crowd of spectators grew. Soon word spread about what happened, and the next day all of Boston knew that what took place on Griffin’s Wharf the night before would have huge implications for the city and colony.