The election was finally over. It was now March 1801 and the dust was settling over the gloom of the new Federal City along the Potomac River. Only the fourth presidential election in United States history, the Election of 1800 proved to be a new low in the young nation’s political tug-of-war for power. Whereas George Washington received unanimous votes each time, the election of 1796 had been the first true competition for seats in the federal government. John Adams, then vice president, received the most votes and won the presidency. At the time, the system was designed to allow the runner up the position of vice president. One did not have to be of the same political party or even on the same ticket to be pitted with each other upon victory. Former Secretary of State Thomas Jefferson won the second most votes, earning him the spot of vice president beneath his longtime political friend, Mr. Adams. However, their once strong friendship that grew from a firm partnership in seeing the Declaration of Independence ratified had recently shown signs of fracture. Throughout the Adams administration, Jefferson undermined his friend whom he increasingly became disillusioned with over policy choices. By the Election of 1800, a severe rift had formed between the two of them. And the election’s results would break them apart for more than a decade thereafter. Bitterness and regret filled memories. It was not always this way.

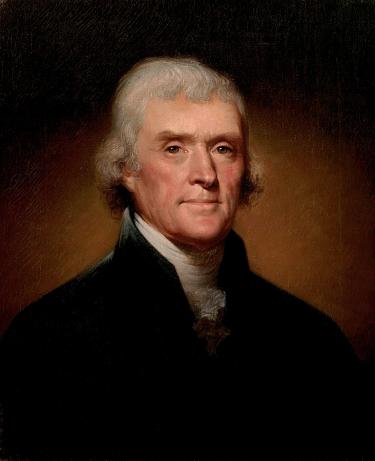

A contemporary once asked Thomas Jefferson what he saw in John Adams. The two men could not have been more different. Jefferson, tall and handsome, of the Virginia gentry and a purveyor in the small government-yeoman-American-utopia, was nothing like John Adams of Massachusetts. Though they both practiced law, Adams was the far superior accomplished legal mind. He had successfully defended the British soldiers on trial for the Boston Massacre. He was also short, stout, and spoke his mind to a fault. He could be cantankerous and wore his thoughts on his sleeve; unlike Jefferson who had developed an astute political eye for deception by never truly revealing what he thought on a subject. At any rate, Jefferson welcomed Adams’ force of nature towards independence at the Continental Congress. Differing styles be damned, what mattered most were those voices advocating for complete separation from Great Britain. In June 1776, Adams and Jefferson were among the Committee of Five to help draft what would become the Declaration of Independence. Though in later years the two differed on who said what, it’s likely true that most assumed Adams would be the one to write the document. Realizing his place within the halls of Congress, the delegate instead approached Jefferson and asked him to write it. Citing how unpopular he was in Congress, and how much he admired Jefferson’s writing abilities, Adams persuaded the Virginian to the task. It’s also likely Adams saw the strategic importance of the document being penned by a Virginian; much like Adams nominating George Washington to command the Continental forces was a stroke of putting a Virginian at the head of the situation, Adams again likely saw the importance in a Virginian, then the most powerful and influential colony in North America, to lead the new resolution. In later years, Adams claimed Jefferson had not written the document by himself, but used the suggestions of the committee, including those of Benjamin Franklin, to craft its careful wording. Jefferson maintained it was solely his work, with input from the others, based on the Enlightenment concepts of John Locke, that inspired it. Either way, Adams rose from his chair on July 1, 1776, in Philadelphia, and during a thunderstorm argued in favor of passing the new declaration. Three days later, after further revisions, the Declaration of Independence became a reality. A mutual respect and friendship was born between the two founders.

During the war, Adams spent much of the time overseas as a diplomat. First, he served in the French Court alongside Franklin, but the two men grew to hate each other’s political styles. Franklin had played the game for decades while Adams, bold and direct in his conversation, offended many of the French intermediaries. He was then dispatched to Holland and throughout Europe to petition the several governments for loans to help finance the American Cause. Meanwhile, Jefferson served as Governor of Virginia for a time. He was nearly captured at his home Monticello by British forces under Banastre Tarleton in 1781. Some criticized him for fleeing under duress. In 1782, Adams shifted back to the lead American diplomatic circles and helped negotiate the Treaty of Paris that ended the war. After peace had been established, Jefferson was dispatched to Paris as a minister of the United States. It was during these years that perhaps served as the critical period of growth and inflection between the two men.

Jefferson had lost his wife Martha in 1782 and the grief that followed nearly crippled him. Joining both John and Abigail Adams in France in 1785 was seen by many as a way for him to overcome his despair, and the experience certainly helped him in many ways. Letters reveal a close bond formed between the Adams and Jefferson, who was accompanied by his young daughter Patsy (and later his other daughter Polly, along with James and Sally Hemings) while there. The two families were inseparable before Adams was dispatched to London. Jefferson remained in France until 1789 as the French Revolution was beginning. Seeing similarities with the American Revolution, Jefferson secretly helped early revolutionaries such as the Marquis de Lafayette pen the French Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen. He returned to the United States in September 1789 when he received word that President Washington had selected him for the new cabinet position of Secretary of State. He would be serving once again alongside his friend, John Adams, who had been nominated as Vice President.

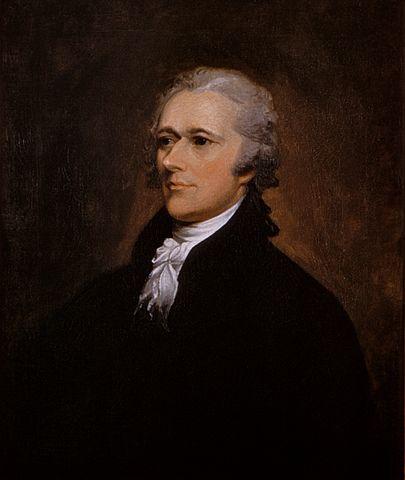

Much had changed in the American political landscape. Since both men had served overseas for the better part of the last decade, they each missed out on participating in key events. Neither was present at the critical Philadelphia Convention in 1787 that saw the creation of the Constitution. From a distance, Adams became a staunch defender of its critical points of creating a strong central government. Likewise, Jefferson saw this as a threat to the autonomy of the individual states. Jefferson and his emerging political disciple James Madison grew wary of the support for the Federalist Party’s policies that were being spearheaded by Treasury Secretary Alexander Hamilton. It would be these disagreements that would set in motion the eventual political turmoil that culminated in the election of 1800.

As vice president, Adams mainly oversaw deliberations in the Senate and was not active in the cabinet’s more important decision making, something he grew to resent. Meanwhile, President Washington maintained an air of neutrality among the emerging political factions taking shape across the country. The Federalist Party had been advocates for ratifying the Constitution and with its victory emerged as the dominant force on the national scene. To counter them remained the faction known as the Antifederalists, those who retained suspicion of a powerful centralized government. To them, the Federalists were northern merchants who were too closely aligned with British interests. The worst charges labeled supporters of their agenda as monarchists. Even Washington himself, a supporter of the Federalist agenda, would have his credibility assaulted by the opposing partisan newspapers throughout his presidency. The Antifederalists tended to be wealthy landowners or planters from the South who held the agrarian mindset that the United States should be less centralized on the national level. Jefferson came to embody the opposition platform better than anyone.

Deals had been struck in 1790 and 1791 to establish Hamilton’s monetary system. The United States would assume the leftover war debts from the individual states to establish credit on the national level. It would also charter a national bank. In return, the southern states would get the national capital when it was completed in 1800. Until then, Philadelphia would serve as the temporary capital. Though distrusting of Hamilton’s plan, Jefferson, like other southern politicians including Washington, saw the value in the South having the capital. It would balance the regional tensions that still existed. For some, it would also guarantee a lopsided advantage to southern interests.

By 1793, Jefferson had grown disillusioned with the partisan politics of Philadelphia and tendered his resignation, claiming he would happily retire to the farming life at Monticello. In actuality, the retirement was very short. By 1795, Jefferson was engaged behind the scenes in partisan battle over the foreign policy crisis. As the French Revolution devoured itself in Paris, Great Britain was harassing American shipping in the Atlantic. Envoys were sent by the Washington administration but nothing was working. Worse, French diplomats in the United States were instigating the fragile tensions among the American citizenry. Americans were divided on the European hostilities. Many wanted peace, while many more sympathized with the French revolutionaries, seeing a clear similarity to the American Revolution just as Jefferson had in 1789. The Federalists openly took the side of Great Britain and denounced the French radicals which angered the Democratic-Republican faction, the successor of the Antifederalists. The Republicans saw themselves as inherently supportive of the French, America’s first foreign ally. At times, war seemed inevitable between the United States and either of or both, European countries.

In 1795, the Jay Treaty prevented war, but it also angered both sides were declaring neutrality in the situation. Washington stood by this position, costing him some of his political clout among supporters. The following year, the first president announced he would not seek reelection. The election of 1796 was the first American election that saw two organized political parties wrestle for the ballot box. John Adams emerged as president with Thomas Jefferson as runner up, making him vice president. At the time, the Constitution stipulated voting to count ballots of candidates regardless of political affiliation. This would change after the election of 1800 showed the chaos that could happen with such an arrangement.

President Adams looked forward to working with his old friend. As vice president, Jefferson would be his most trusted advisor. The president saw this as a chance to mend the fences between the two political factions and solve many of the lingering problems of the decade, including among themselves. Their friendship had waned in the years since Paris. In 1791, Jefferson had called Adams a ‘heretic’ behind his back for his defense of a strong executive. The remark struck Adams and the two drifted away from each other, especially after Jefferson retired. However, following the election results, Jefferson attempted to soothe the waters and assured Adams their political differences would not obstruct the administration’s competency. Jefferson trusted Adams to a fault, but he did not trust the men in Adams’ administration. Much to the vice president’s anxieties, the Adams administration retained three of Washington’s advisors and cabinet secretaries: James McHenry, Timothy Pickering, and Oliver Wolcott. Though Adams was a Federalist, these Federalist men were not loyal to him. They had been loyal to Washington and remained loyal to Alexander Hamilton, now out of government himself, but pulling the strings from behind the scenes. Hamilton detested Adams, saw himself as the heir apparent to Washington, and instructed his men to undermine the president wherever they could. In return, Hamilton would be the one stealthy directing policy decisions from the shadows. Jefferson saw the scheme right away and warned Adams, but the president dismissed him as paranoid.

Perhaps the two biggest policies of the Adams administration were the XYZ Affair and the Alien and Sedition Acts. The first exposed a political bribe demanded by the French before they would receive American diplomats. When the bribe reached Adams, it was decided to make it public in order to damage those opposing peace negotiations, including Republicans who were still very much pro-France. At the height of the Quasi-War Crisis, Hamilton was coordinating a build up of a new provisional army. As inspector general, he set about raising a standing force that could oppose any invasion. Adams supported strengthening the US Navy but increasingly grew suspicious of Hamilton’s true motives, at one point privately referring to him as ‘Caesar.’ Meanwhile, tensions between American partisans boiled over. In 1798, rival Congressional members attacked one another on the floor of Congress with a cane and fire tongs. High or Ultra-Federalists sought to declare war against France in the summer of 1798. With Hamilton distracted building the armed forces, his control over these radicals weakened. As the XYZ Affair was exposed, patriotism rallied behind President Adams. However, it was with this support that the radical elements in the Federalist Party overplayed their hand.

Despite the reservations of Hamilton, the radical factions of the party pressed to pass the Alien and Sedition Acts, which allowed for the federal government to deport any immigrant who was a ‘threat to the peace or to the government. Matching that were the Sedition Acts that stipulated any individual criticizing the government, including the president, could be arrested. This undoubtedly was directed at the partisan press who were attacking the Federalist agenda. Adams signed the legislation and later poorly defended his reservations with doing so. The immediate consequences were apparent to all Republicans, including vice president Thomas Jefferson. The political divide between the two men, and their parties, had now reached a critical impasse.

Jefferson responded by ghostwriting the Virginia and Kentucky Resolutions. These pamphlets argued that states had the authority of nullifying any federal law that they felt was unconstitutional. It quickly caught fire with partisans and Americans distraught with how the Federalist Party came to increasingly symbolize a hierarchy within the American political class. As this groundswell was occurring, Adams sought to send another peace envoy to France in 1799. The president remained committed to Washington’s policy of neutrality. Knowing that his cabinet secretaries and the radical Federalists would oppose his move, he announced the departure in February. Immediately, the Federalist press turned against him. Adams postponed the envoy’s departure until initial accommodations could be made to gain bipartisan support. This provided some radicals with the perfect opportunity to delay the envoy indefinitely. Throughout the summer, Adams watched from his Massachusetts home as his secretaries devised a plan to keep the envoy stalled from departing. Eventually, Adams returned to Philadelphia where he met with Hamilton face-to-face. The meeting did not go well. Adams railed against him for undermining his presidency and dismissed him. He also fired the leftover cabinet secretaries, severing himself from Hamilton’s influence once and for all. The French envoy finally departed in November, a full eight months from its announcement. Its delay would prove costly in the election of 1800.

Hamilton did not waste time to respond to his treatment from the president. Published in Federalist newspapers, his Letter….concerning the Conduct and Character of John Adams, became a salacious account of partisan infighting that threatened to rupture any cohesive agenda within the party. Hamilton did not come off well from its publication. It politically weakened him among the party as even Federalists called his charges negligent and egotistical. At the same time as Hamilton sought to discredit Adams, the divide within the party’s apparatus had hampered its ability to rally support among political candidates. Republican gains in the midterm elections of 1798 were showing signs of a growing movement, but the Federalist leadership remained confident their decade-long hold on the reigns of the government would last. What they failed to appreciate was how successful Jefferson and his allies had been in stoking fears of Federalist-backed government initiatives. The Alien and Sedition Acts were regularly used in the pro-Republican newspapers to rile up voters who were already skeptical of the national government. The Republicans also seized on the growing consent of the many American citizens who were not part of the political process. For the first time, lowering the standard to vote in elections became a topical issue. The Republicans, branding themselves as the party of the yeoman and advocates of smaller, disorganized power, came to support a more democratic electorate. Even champions of the Constitutional Convention like James Madison, who greatly feared rampant democracy, were now Republican supporters of expanding voting rights to virtually all white male citizens, regardless of property ownership and community status. They also championed the separation of church and state, the freedom of the press, and proclaimed to be the true stalwarts of the American Revolution’s legacy.

The campaign and election of 1800 are rightfully remembered as being both bitter and divisive. Perhaps no other election, save for the elections of 1824 or 1828, conjured up more partisanship than the one between Adams and Jefferson. The partisan newspapers ran attack ads daily. Adams was called all things, including a hermaphrodite. Jefferson was labeled an atheist and a dangerous man. Both lead candidates remained largely detached from the political rancor, though Jefferson certainly played a greater role in directing editors what to print.

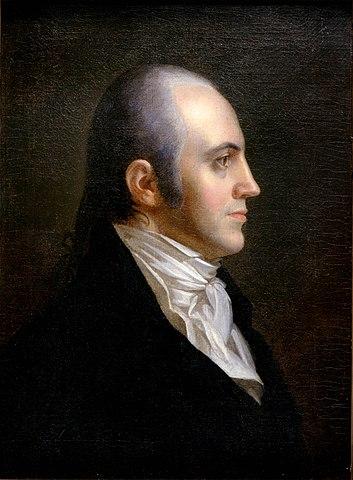

As president, Adams was campaigning for reelection. At times, he privately confessed his yearning for retirement, but he also remained a political fighter who could not see himself bowing out, particularly to forces he vehemently opposed. To rally party unity, the Federalists chose South Carolina’s Charles C. Pinckney as his running mate. The Republicans nominated Jefferson and New York’s Aaron Burr as his vice president nominee. Because of the way the Constitution was written, the delegates in the electoral college could cast two votes each. It could mean the party’s two candidates could be divided if one came in second in the overall tallies, such as Jefferson becoming vice president under Adams and a rival political party. This had caused problems in the previous election, and would largely define the current election’s outcome.

Election day was December 3, 1800. By this point, the contest had already produced several results. One such result showed that neither political party was above the standard of playing fair. In Georgia, Virginia, and New York, rival factions switched voting district regulations in favor of the majority. Balloting had been underway for weeks, and the clear result showed that Adams was coming up short in key areas that had previously been Federalist strongholds. Indeed, the incumbent worried he would receive fewer votes than his running mate Pinckney. In the end, Adams would receive 65 votes to Pinckney’s 64. However, both Jefferson and Burr received 73 each, creating a tie for the presidency. Burr had been a controversial pick from the outset. Though a generation younger than Jefferson and not his equal in politics, the younger candidate was equally ambitious. Too ambitious for some, including rival Alexander Hamilton. When the Republican ticket was assembled, Burr made it clear he would run behind Jefferson, as it was widely accepted that Jefferson was the literal face of the party. Burr even indicated this to the future president. However, as the election resulted in a tie between the two men, Burr suddenly indicated to some that he intended to fight for the presidency, reversing everything he had promised up until that point.

The following weeks provided the necessary actions to see a victor emerge from the stalemate. And the person who cast the fate of the election was none other than Alexander Hamilton. We would assume Hamilton would do everything in his power to deface and eliminate Jefferson, his longtime political enemy. But Hamilton felt Burr was actually the greater political threat. Though he differed immensely with Jefferson ideologically, he also knew Jefferson to be temperate towards government power. Burr, on the other hand, was viewed as dangerously ambitious and could not be trusted with the reigns of the federal government. Hamilton secretly put together his terms for rallying Federalist support to Jefferson: the next administration could not undo the financial and bank system; it could not remove Federalist appointees and it had to preserve the US Navy, among other things. Hamilton had his scheme while other prominent Federalists disagreed and still viewed Jefferson as their ultimate target to defeat. Yet the same pitch was made to Burr who rejected such an agreement.

Starting on February 11, 1801, thirty-five votes were conducted in the House of Representatives over the next five days to choose a victor. All remained deadlocked in a tie. As the partisan infighting occurred, real threats of insurrection broke out across the country. Many factions aligned with the Republicans threatened to act if the election was stolen from Jefferson. Recall, this was shaping up to be the first real transfer of political power at the national level; the Federalists had held the presidency since 1789. Rumors circulated of a government coup d’etat and even a plan to assassinate Jefferson if he tried to take the presidency without consent. Finally, a compromise was broached with Delaware’s James Bayard, a Federalist, and Maryland and Vermont, two states that remained deadlocked. If Bayard abstained from voting, it would lower the state threshold needed to break the tie. As this was being debated, Jefferson came to the decision to accept the terms of Hamilton’s scheme. Though never admitting it, his administration would not challenge a single stipulation put forth by his longtime political rival. The Federalist plan was now set. On February 17, during the thirty-sixth vote in the House of Representatives, Delaware abstained and did not cast a vote. The Federalist delegates of Maryland, South Carolina, and Vermont also did not vote, allowing for Jefferson to now claim a clear majority of the delegates that offset those that were no longer being counted. Thomas Jefferson had officially become the president-elect of the United States.

On March 4, 1801, President Jefferson walked the dirty streets of the new capital of Washington City to the steps of the incomplete Capitol building. In the halls of the Senate, the new president, visibly nervous and not a strong speaker, promised to mend the bitterness of the last few years by declaring, “We are all republicans, we are all federalists.” Adams did not attend the inauguration. Having accepted defeat in the early winter and largely remaining unseen for the remainder of his term, the former president slipped away by carriage in the early hours of Inauguration Day. His last great act as president was nominating John Marshall to be Chief Justice of the Supreme Court. Marshall, a vocal Federalist who despised Jefferson, nonetheless was the individual who swore in the third president.

President Jefferson liked to reflect upon his election victory as the “Revolution of 1800,” believing that his — and the Republican - victory had upheld the principles of the American Revolution, beating off the illegitimate forces that sought to destroy it. In truth, it’s hard to see the election as a true revolution. The Federalist Party continued to lose its grip on national affairs and would completely dismantle as a functioning unit after the War of 1812. Jefferson owed his victory as much to the bad policies of the Adams administration as he did to the way the Constitution favored the southern states. Removing the three-fifths clause of counting enslaved persons as a fraction of a person, thus increasing the south’s population and a number of delegates in the House of Representatives to Jefferson surely would have tipped the election to Adams had that not been law. Also, Adams’ delayed peace envoy to France returned far too late in the year 1800 to persuade voters that his policy of neutrality had indeed been successful. Had it departed when Adams initially planned, it perhaps would have returned in time to show his administration’s success in keeping the United States out of a European war. Lastly, though Adams lost the election, he actually favored better than down-ballot candidates in the Federalist Party. It appears voters trusted him personally over that of many within the party’s numerous congressional races. After all of Hamilton and Jefferson’s attacks, Americans generally had a favorable opinion of the now one-term president. Nevertheless, Adams would remain bitter of his defeat for years to come.

The former president spent years writing a reply to Hamilton’s Letter, though it was published posthumously after Hamilton’s fateful duel with Vice President Aaron Burr in 1804. Hamilton had never politically recovered from the election. For his part, Burr was largely marginalized in Jefferson’s administration and was replaced in the election of 1804 with George Clinton, Governor of New York. His career would take dramatic turns in the coming years as he sought personal fame and wealth at the expense of the United States in the Mississippi territory.

Adams and Jefferson remained at odds in the first decade of the nineteenth century. The retired elder statesman worked his farm in Peacefield and wrote his memoirs while Jefferson ran the country, expanding it to great success with the Louisiana Purchase in 1803. But the two had ceased communicating. It would take several prompts from friends to bridge the gulf between the two. Adams struck first with a letter in 1812, triggering a correspondence that lasted for the better part of the next fourteen years. As history accurately records, the two founding fathers died on July 4, 1826, fifty years to the day of American Independence. It seemed to many then, as it does now, that fate had played a hand in signaling their respected ends on that day of all days.

What can be said of Adams and Jefferson is the two men symbolized many aspects of the Founding generation, and of its several conflicting ideals. These ideals often played on each other, sometimes suggesting different means of achieving certified goals. But neither men remained committed to more than seeing to it that the young nation they helped found would succeed. It was that shared vision that bound to two for their entire adult lives. Even in heated disagreement, there remained a curious respect and affection for one another. The years of build-up that culminated in their rival campaigns signified a testing of two branches of political thought: one of strong central government and one of a weak, indifferent central government. Indeed, those very divisions loom long over the American character into today. But the election’s true success story is seeing the peaceful transfer of power among rival political factions. Perhaps this revolution better stated the importance of American leadership and republicanism. In this sense, Jefferson was right.

Despite the Election of 1800’s pivotal outcome, what it shows us is how American politics would shape the country in the decades moving forward. Sectional tensions that were not settled, and perhaps irreparably enshrined, would come to challenge the country’s very existence and identity in the nineteenth century. Many of the founders, including Adams and Jefferson, worried about these divisions. But they had cast their lot with those who favored national unity above all else. The election showed that some aspects of their vision were imperfect. It also showed how American politics would operate hereafter.

Further Reading

- The Jeffersonian Republicans; The Formation of Party Organization, 1789-1801 By: Noble E. Cunningham Jr.

- Adams vs. Jefferson: The Tumultuous Election of 1800 By: John Ferling

- Thomas Jefferson: The Art of Power By: Jon Meacham

- New Jersey’s Jeffersonian Republicans, The Genesis of an Early Party Machine, 1789 - 1817 By: Carl E. Prince

- The XYZ Affair By: William Stinchcombe