“The paymaster has not a single dollar in hand” General George Washington wrote to the president of the Continental Congress John Hancock while conducting the Siege of Boston in 1776. A variation of this line permeated throughout the next seven years of war, as Washington, the Continental Congress, and the various states struggled to pay the soldiers that won American independence.

With the move toward creating a Continental army after the actions in Massachusetts, the Continental Congress set the pay for the first non-New England recruits. These riflemen, hailing from Pennsylvania and Virginia, that served as privates would be paid $6.67 per calendar month. As the year 1775 unfolded, captains in Continental service would earn $20 a month and the pay would increase as the ranks did, with a colonel collecting $50 per calendar month.

After a debate in Congress, a committee was created in October 1775 that included Washington and delegates from some of the New England states to recommend a rate of pay for soldiers that would enlist in Continental army service for the following year. The debate on whether to decrease the pay was considered and dismissed, along with deeming it improper to increase the pay of officers, calling the latter “inconvenient and improper.”

As the war progressed and inflation of Continental currency skyrocketed, by 1781 the rate was $225 Continental paper dollars to every $1 dollar in hard specie, the pay of the soldier did not keep up. In fact, the Continental Congress took over two years to revisit the pay structure from those sessions in late 1775. In May 1778. A colonel in the infantry saw a bump in salary from $50 to $75, a captain to $40 from the $20 they had been earning, yet the poor private soldier did not see an increase.

With paltry pay, harsh living conditions, and a chronic shortage of supplies, service in the Continental army was arduous before even stepping onto the battlefield. To compensate for the low wages, the various states offered bounties for enlistment on top of what the enticement by the Continental Congress was. These incentives could include land and clothing as part of the deal. Officers, upon the recommendation of Washington, were also offered half-pay for life as an inducement to continue their service.

In one account, the town of Salem, Massachusetts offered prospective recruits in June 1780, a few dollars’ worth of hard specie, several hundred dollars’ worth of Continental paper money, and half a dozen head of cattle to be delivered when the soldier mustered out. For those on the bottom rungs of society the chance to collect after service was a gamble worth taking.

The lack of pay continued to haunt Washington throughout the war. During one of the darkest time periods of the war at the end of 1776, Washington, in addition to volunteering to dip into his own personal fortune leaned on Robert Morris, signer of the Declaration of Independence, and financier to scrape together any hard specie he could find to entice the soldiers to stay on for an additional six weeks into 1777. Each soldier was paid $10 bounty. The supposed hard specie handed out was a motley collection of coins from various nations.

Later in the war, Washington and his officers had to put down unrest and a few mutinies based on lack of pay for the soldiers. One of the more severe mutinies was the Pennsylvania Line in 1781 while encamped at Morristown, New Jersey. Soldiers who had signed for “three years or the duration” believed that their time was up with the turn of the year and disheartened by their measly $20 bounty at their time of enlistment, especially when newer recruits were receiving more. In fact, newer recruits in Pennsylvania were receiving quite larger inducements to muster in. The Pennsylvania Line stormed out of their winter encampment en-route to Philadelphia. Upon reaching Princeton, New Jersey, the mutineers set up a temporary headquarters where General Anthony Wayne, their commanding general, caught up with them. Upon hearing grievances, the situation was settled, and a compromise reached, Pennsylvania soldiers who had mustered in for the $20 bounty would see their enlistment expire and could resign for a larger inducement. Other mutinies did not end in the same manner though; a mutiny by the New Jersey Line saw two of the main instigators executed.

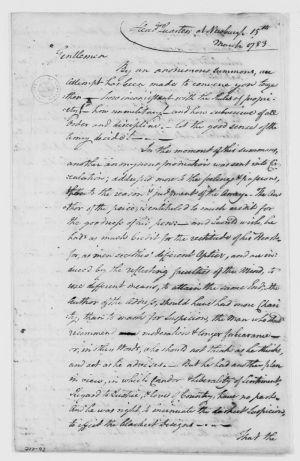

Both mutinies show the lack of consistent pay and exorbitant bounties to entice recruits to join the military effort. A matter that Congress could never completely control or streamline, which caused frustration throughout, from rank-and-file to the officer corps. Besides the mutinies listed above, the officers protested in 1783, fearful that the war would end without Congress honoring their commitments. In Newburgh, New York, in one of his greatest speeches and public displays, Washington asked for the trust of his officer corps in handling the situation. Seeing their commander wear spectacles to read his speech, the men gathered broke down and Washington quelled the unrest.

Near the end of the conflict in 1783, soldiers received three months pay from Congress, as that political body decided a large army was not needed further. There was only one problem, Congress did not have the funds to actually pay the soldiery, so Robert Morris issued $800,000 in personal notes. However, these promissory notes were almost worthless and many a speculator bought them cheaply from the rank-and-file before they left camp. Many soldiers sold the notes to pay their way home to loved ones.

States and Congress producing their own money and debt bonds or certificates, along with foreign loans from France, Spain, and the Dutch added a mixture of currency in circulation throughout the thirteen original colonies. When and if pay did arrive, soldiers could expect either paper currency issued by their respective state of Congress that lost value consistently throughout the seven-year conflict or if lucky maybe a few hard coins of currency. The soldier could also earn that promised land bounty or like that soldiers in Massachusetts, a few head of cattle to start a farm with.

The American Revolution was won by an army that was underpaid, when it was actually paid, and received their dues in paper currency that was near worthless but fought on with promises for the future.

Related Battles

19

79

75

270

1,111

533

1,900

324