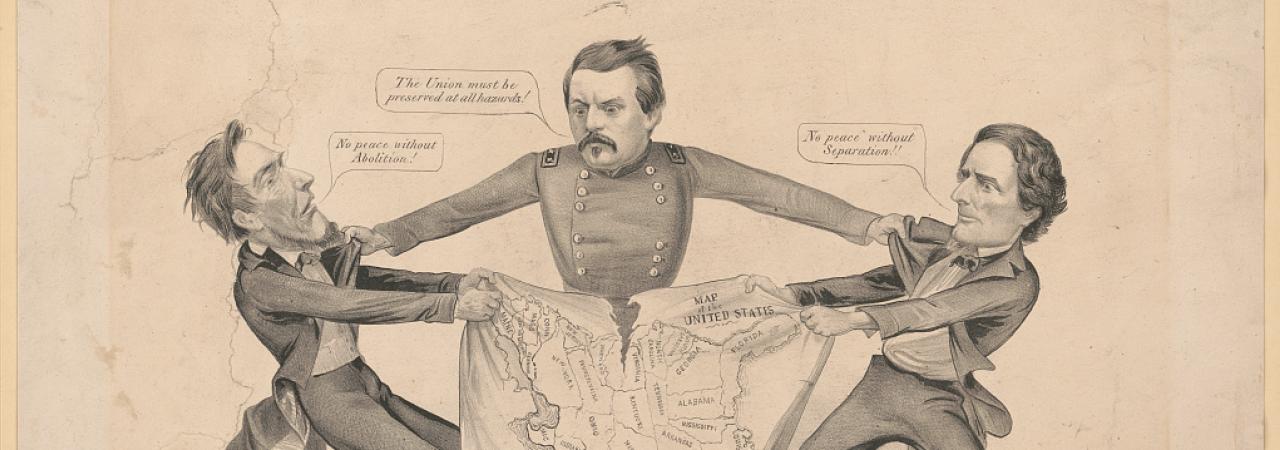

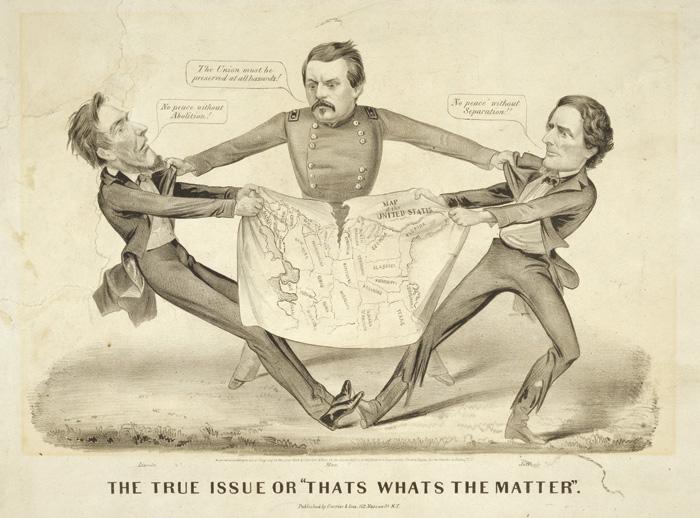

In this Currier & Ives cartoon, George B. McClellan is portrayed as the intermediary between Abraham Lincoln and Confederacy president Jefferson Davis. McClellan is in the center acting as a go-between over a "Map of the United States." He holds the two men by their lapels and asserts, "The Union must be preserved at all hazards!"

The presidential election of 1864 was a remarkable example of the resilience of the democratic process in a time of extreme national uncertainty and chaos. The last presidential election to take place in wartime had been in 1812.

More than for just a candidate, voters cast their ballots to determine questions underpinning the broader fate of the Union: Should the war be continued, or should a peace settlement be negotiated? How would the outcome of the war define the role of blacks in a post-war society?

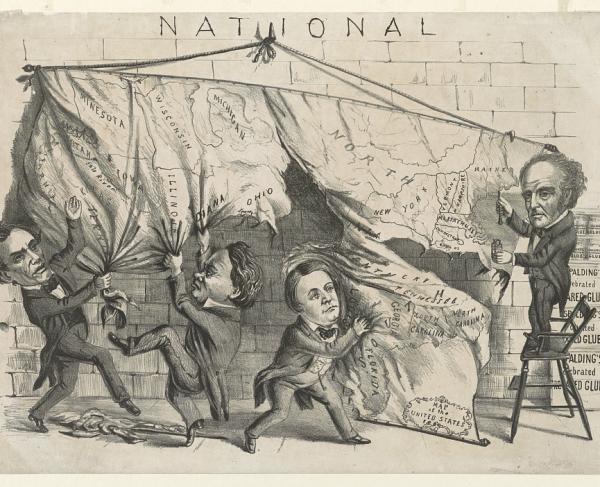

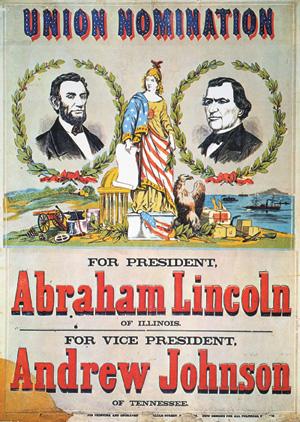

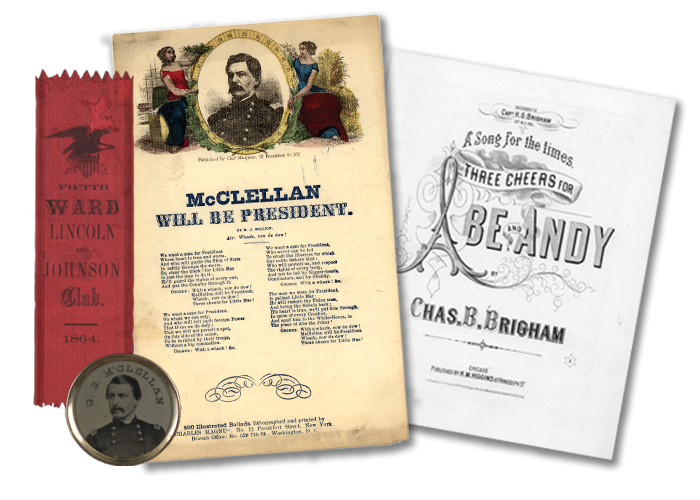

The election pitted incumbent Abraham Lincoln and his running mate Andrew Johnson, the military governor of Tennessee and a former U.S. Senator from the Volunteer State, against former commander of the Army of the Potomac, Maj. Gen. George B. McClellan and running mate George Pendleton. McClellan ran on a peace platform — the consensus platform of the faction-wrought Democratic Party. Republicans and a number of War Democrats together formed the National Union Party, which backed Lincoln as its nominee.

An incumbent candidate had last been elected for a second term in 1832, and Lincoln’s shift to include emancipation in his war aims was troubling for many Northern voters. Union Lt. Gen. Ulysses S. Grant seemed unable to administer a definitive blow in Virginia, and as the brutal summer of 1864 wore on, his armies continued to suffered staggering losses. War weariness was rampant, as Union armies struggled to overwhelm Southern forces, notching bloody defeats at Mansfield (La.), Cold Harbor (Va.), Kennesaw Mountain (Ga.) and the Crater (Va.).

Lincoln wrote a dour memorandum on August 23, 1864, asking his cabinet to accept the grim prospects for his re-election:

This morning, as for some days past, it seems exceedingly probable that this Administration will not be re-elected. Then it will be my duty to so cooperate with the President-elect as to save the Union between the election and the inauguration; as he will have secured his election on such grounds that he cannot possibly save it afterwards.

The political landscape shifted dramatically, however, when Gen. William T. Sherman took Atlanta in early September. This major military shift, coupled with the severe internal strife within the Democratic Party, solidified Lincoln’s chance at victory.

As the election drew near, the Union Party mobilized the full strength of both the Republicans and the War Democrats with the slogan “Don’t change horses in the middle of a stream.” A resounding and dramatic Union victory at Cedar Creek in Virginia’s Shenandoah Valley in mid-October added a final wave to Lincoln’s tide of momentum.

The 11 Confederate states did not participate in the election, meaning only 25 states participated. The newly incorporated states of Kansas, West Virginia and Nevada participated in a national election for the first time. Elections were held in Union-occupied military districts in Louisiana and Tennessee, but Congress did not add their electoral votes to the final count.

When all the votes were tallied, Lincoln won the election in a landslide, defeating McClellan by more than 500,000 popular votes and 191 electoral votes. An estimated 78 percent of Union soldiers cast their ballots in favor of Lincoln. McClellan took just three states: Kentucky, Delaware and his home state of New Jersey.