By Philip Lee Secrist

The Atlanta Campaign of 1864 would have been impossible without the road [Western and Atlantic Railroad], that all our battles were fought for its possession, and that the Western and Atlantic Railroad of Georgia should be the pride of every true American because by reason of its existence the Union was saved. Every foot of it should be sacred ground because it was moistened by patriotic blood, and that over a hundred miles of it was fought a continuous battle of 120 days, during which, day and night, were heard the continuous boom of cannon and the sharp crack of the rifle.

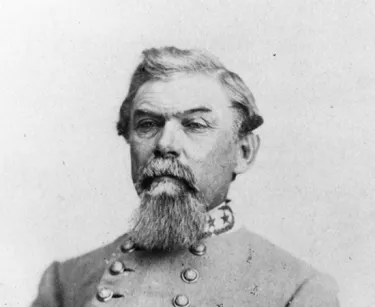

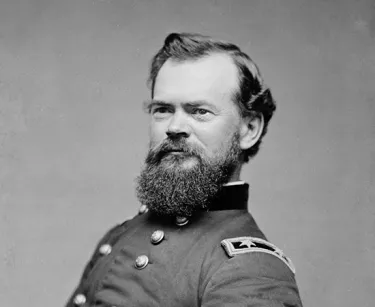

Sherman’s campaign to defeat General Joseph Johnston’s Confederates and capture Atlanta had commenced in north Georgia in May 1864 at Mill Creek Gap near Dalton. Sherman’s command was actually a group of three armies officially designated the Cumberland, the Tennessee, and the Ohio, and commanded respectively by generals George Thomas, James McPherson, and John Schofield. Of the three, Thomas’s Army of the Cumberland was by far the largest, numbering 55,000 men – alone nearly equal to the total numbers in the opposing Confederate army.

Part One: Tactical Disasters

Sherman’s first thirty days in this campaign had not exactly been easy. Thirteen miles south of Dalton, at Resaca in Gordon County on May 14 – 15, Union and Confederate opponents faced off in full strength for the first time. Here they fought to a draw in two days of hard fighting. No mere skirmish, casualties at Resaca were substantially greater than those suffered three years before in the war’s first battle at Bull Run in Virginia. Employing his advantage in numbers, Sherman disengaged late on the second day at Resaca using a river crossing south of the field, thereby forcing Confederate withdrawal to protect lines of rail supply and paths of retreat to Atlanta. The flanking movement would become Sherman’s tactical signature in this contest for Atlanta.

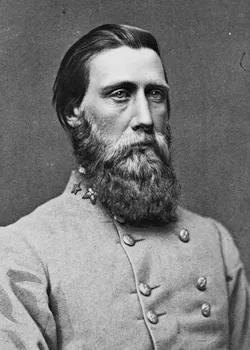

The events of the days ahead would follow this pattern of Confederate retreat and Union pursuit southward to the Etowah River. In mid-May Johnston’s Confederates had the opportunity to destroy an isolated portion of Sherman’s army near Cassville (Bartow County) but squandered the chance. Here, Confederate General John Bell Hood spoiled the timing for the entire two-corps attack by halting his advance midway in the mistaken belief that Union infantry threatened his flank.

After the Cassville fiasco, the Confederates continued their retreat to the Etowah River; crossing the river, burning the railroad bridge behind them, and taking up defensive positions south of the river in the rugged Allatoona hills. Aware of the character of these hills from a personal visit many years before, Sherman chose to suspend his direct advance along the railroad. Disposing his army along the north side of the river westward some ten miles to Kingston, Sherman set about devising a new ten-day strategy which would carry his army directly southward through the tangled wilderness countryside. He would temporarily abandon his rail line in favor of a mule-drawn wagon alternative. Surely a risky strategy, he reasoned, but it would force Confederates to abandon their impregnable Allatoona forts in order to protect their flanks and railroad. With a head start he might even beat his opponent to those country crossroads near Dallas and New Hope Church – roads that led directly to Atlanta, bypassing the formidable fortress now being constructed at Kennesaw Mountain in Cobb County. The complete dependence on wagons and mules to supply his immense army in this landscape of bad roads and worse maps was a bit unnerving. Still, the risk seemed reasonable and the goals worth it. The move could certainly offer an opportunity to choose his fields of battle, and perhaps even gain a rapid and politically timely capture of Atlanta!

The Union soldiers in this battle would come to call the crossroads at New Hope Church the “Hell Hole.” By May 25, having waded the Etowah River several days earlier, the various Union march columns were converging rapidly on Dallas. Union General Joe Hooker guided his Twentieth Corps (a component of the Cumberland army) along a wagon path leading toward a place known as Owens Mill, on a creek called “Pumpkinvine.” He hoped to reduce his march time to Dallas by avoiding the congestion of military traffic on the main routes.

John Geary, commanding Hooker’s first division, led the way. Approaching the mill, Geary received rifle fire from the ridge beyond; a brigade was deployed across the creek to drive off the Confederate skirmishers. These first few shots signaled the beginning of the Battle of New Hope Church.

Geary, alarmed by the aggressive manner of the small band of Confederate skirmishers in his front, concluded, therefore, that a large Confederate force must lie just beyond. He postponed his attack three hours while awaiting the arrival of Butterfield’s and Williams’s divisions. It was almost 5 p.m. before the three Union commands began their movement toward the New Hope Church crossroads.

Things went downhill from the beginning. First, a terrific thunderstorm with frequent lightning and heavy downpours of cold rain set in shortly after 5 p.m. Complicating this, the Union commanders decided upon an ill-chosen formation: a column of divisions by brigade. Such a formation, while improving command control, exposes the flanks of the approaching column to rifle crossfire while offering very little opportunity to return such fire. At New Hope Church this formation had the effect of negating a three-to-one Union numerical advantage. An under-strength division of Confederate infantry in position at the church cemetery, without earthworks, had little difficulty stopping the attack 300 yards short of its objective at New Hope Church. The assault ground to a halt by nightfall. The night was a disaster of confusing orders, pitch black darkness, cold rain, and desperate men entrenching in ravine-laced wooded thickets strewn with the wounded and dead. That night the place truly earned its long remembered epithet: “The Hell Hole at New Hope Church.” Having suffered nearly 2,000 casualties at New Hope Church, and with the fast-marching Confederate infantry already covering the key Atlanta-bound roads near Dallas, Sherman reviewed his options. On May 26, frustrated by the tactical disappointments but also by the increasing supply shortages, Sherman decided to abandon his “wilderness” plan in favor of returning to the supply security of the more dependable railroad. But first he would try to locate the east flank of the Confederate earthworks.

The Fourth Corps of the Cumberland army was chosen for the task. Should an attack be possible, the Fourth Corps was to be supported by units from the Army of the Ohio and the Fourteenth Army Corps. The battle at Pickett’s Mill began shortly after 4:30 p.m. As at New Hope Church two days before, it was again a tactical disaster for Sherman. In that blind wilderness, three good brigades from the Fourth Corps suffered nearly 2,000 casualties and gained no great advantage. A witnessing Union officer described this mismanaged attack as “The Crime at Pickett’s Mill.” Sherman curiously made no mention of the battle in his official report, nor still later, in his Memoirs.

On May 28 it became the Confederate turn for tactical mistakes. Suspecting correctly that McPherson’s Army of the Tennessee at Dallas was preparing to shift eastward toward New Hope Church and the railroad, General Johnston instructed Hardee to attack immediately should he detect any such movement. Hoping to catch the Union infantry off balance while in the act of shifting position, Hardee ordered Bates’s division to carry out the task by striking simultaneously at two geographically separated points: one at the Villa Rica Road south of Dallas, and the other a mile distant on the Marietta Road east of the village. Curiously, the signal to attack was to be the sudden sound of heavy gunfire at the south end of the line. Confused by gunfire from a related cavalry action near the Villa Rica Road, a Kentucky unit on the Marietta Road prematurely launched a full-scale assault. This unit, the famed Kentucky Orphan Brigade was so badly mauled by being caught in a crossfire that it was subsequently disbanded. Bates’s division became entangled with the enemy and had difficulty disengaging, requiring Hardee to commit additional units from his command to the rescue. The battle continued for the better part of the day along the entire Dallas line. Confederate casualties on May 28 are estimated to have exceeded 1,000 men.

Sherman’s continued movement eastward to the railroad eventually placed McPherson near the south bank of the Etowah River where he set about repairing the river bridge and the rail tracks south toward Acworth. Meanwhile, the Cumberland and Ohio armies entered Cobb County from the west following the Stilesboro and Burnt Hickory Roads and colliding almost immediately with a formidable 12-mile line of fortifications known as the “Lost Mountain/Brushy Mountain Line.”

Part Two: Cobb County - Field of Battle/Seas of Mud

Elements of Sherman’s army began arriving in Cobb County on June 2. Daily rains began June 3 and lasted for two weeks. Wagons and artillery caissons were soon buried to hubcaps – all traces of roadways disappeared in seas of mud. Wheeled vehicles would use the “road.” Infantrymen, required to slog through the fields alongside the roads, endured the misery of rough terrain and briar patches, with full exposure to swarms of ticks, red bugs, and mosquitoes. Tents pitched between puddles of water at an evening campsite, amid downpours of rain and swarming insects, promised little rest after a miserable day.

As the Cumberland and Ohio Armies entered Cobb County they collided almost immediately with the Lost Mountain/Brushy Mountain Line.

In early June the battle line was occupied near Lost Mountain by the four divisions of Hardee’s corps, with the three divisions of Polk’s corps being next in line eastward. Hood’s three divisions manned the Brushy Mountain third of these fortifications. Sherman knew the Confederate infantry was too small to sufficiently cover such a distance. Hardee’s men occupied the works westward only as far as the Burnt Hickory/Sandtown road intersection (Acworth Due West Road today). His left was anchored near the log church of Gilgal. This location would become a military landmark in the days ahead. The defense of the mile or so of trenches westward to Lost Mountain became the responsibility of Confederate cavalry. By June 5, Hardee had moved Bates’s division a mile north to the crest of Pine Mountain, a hill overlooking Thomas’s advance along the Stilesboro Road. Polk’s corps slipped a division length westward to link with Hardee, covering the absence of Bates in the battle line. On June 14, Hardee, Johnston, and Polk met at Pine Mountain, concerned that Bates’s division was becoming isolated by Union movement near its flanks. Atop the mountain, the meeting ended tragically with Polk’s death by artillery projectile. A gun a mile away near the Stilesboro Road had fired the chance shot. Today a well preserved four-gun earthwork marks the site of that Union battery. Southward at the crest of Pine Mountain, infantry and artillery entrenchments share the location with a granite shaft memorializing the place of Polk’s death.

Since the Stilesboro and Burnt Hickory Roads run roughly parallel in a southeasterly direction toward Kennesaw Mountain and Marietta, it is not surprising that Union armies using these roads frequently engaged in joint military actions during the first two weeks in June. One such occasion occurred on June 15 at the Battle of Gilgal Church/Pine Knob. The purpose of this attack was to probe and possibly break the overextended Confederate battle line, forcing a precipitous retreat.

Sherman had chosen Hooker’s Twentieth Army Corps for the task with units from the Ohio army protecting the Twentieth Corps’ right flank. By mid afternoon on June 15, Daniel Butterfield’s division approached the Burnt Hickory/Sandtown roads intersection intending to strike the Confederates entrenched at the crossing. Planned as a coordinated assault by Hooker’s three 5,000-man divisions (Butterfield’s, Geary’s, and Williams’s) on a mile-wide front extending from Gilgal eastward to Pine Knob, much depended on timing and inter-divisional communication. Neither of which would be forthcoming.

Judging that Butterfield had gotten in position a mile west on the Sandtown Road, Geary and Williams at the foot of Pine Mountain began their advance southward around 5 p.m., guiding on a distant wooded hill they called Pine Knob. With Geary’s men leading and Williams’s following closely, they began a ridge-by-ridge struggle toward Pine Knob, the hill believed to mark the location of the Confederate battle line.

Upon contact with the principal Confederate defenses, Williams’s division was to slide westward, protecting Geary’s right and tying with Butterfield’s left, thus forming a united three-division battle front for the final assault. Ridge-creased terrain, stubborn resistance by Confederate skirmishers, and approaching nightfall defeated the plan. The final assault never materialized. Today, a 20-acre wooded tract with earthworks marks Butterfield’s battleground at Gilgal; one mile east, a 5-acre history preserve with a historical marker locates the forward-most position gained by Geary that night at Pine Knob. Sherman’s casualties in this failed effort are estimated to have been just fewer than 1,000 men. That same day a diversionary attack by McPherson at the foot of Brushy Mountain was more successful, netting the capture of some 300 Alabama infantry. Tactically, it was the one bright spot in Sherman’s otherwise rather dismal day.

The tactical defeat on the 15th evolved into a strategic advantage for Sherman two days later. Learning that Confederate cavalry had abandoned their trenches toward Lost Mountain, leaving his flank exposed to enfilading artillery fire from the Army of the Ohio, Hardee withdrew several miles to the east bank of Mud Creek the night of June 16. Here he anchored his right on a steep hill (now called French’s) tying to the left of French’s division of Polk’s corps (now commanded by Loring), forming here a pivot or salient. Hardee’s left would simultaneously swing south two miles to a position along the east bank of Mud Creek to a point just beyond the Dallas/Marietta road. Thus Hardee substantially reduced the length of his front and better protected his flanks. This new alignment of fortifications became known as the “Mud Creek Line.”

On the 17th at the Mud Creek Line, in a sudden dash during a thunderstorm, three regiments led by one-armed Colonel Frederick Bartelson (wounded at Chickamauga and a recently returned prisoner of war from Libby Prison) captured a position near French’s Hill. Equipped with Spencer repeating rifles, they succeeded in holding the point through the night despite several Confederate counterattacks. Bartelson’s location posed a serious threat to the new Confederate line of defense. On the 18th, French’s division was pounded by a day-long crossfire of Union artillery. On the same day, at the Dallas/Marietta road near the Darby House, Hardee’s anchor fort was destroyed in an intense three-hour duel with two Union batteries attached to the advancing Army of the Ohio. In the predawn hours of June 19, the Mud Creek battle line would be abandoned. The Confederates withdrew to the foothills of Kennesaw Mountain.

On the 20th, the Josiah Wallis House on Burnt Hickory Road became the headquarters of General Oliver O. Howard, commander of the Fourth Corps. Here, for the next few days, Howard directed the attacks on nearby hills – including division-size assaults on hills lying behind the knee-deep swampy flats of Noyes Creek. One of these hills would later be called “Nodine’s” following heavy combat there in mid June. Kirby’s and Nodine’s brigades gained and lost the hill several times on June 20. Reinforced the next day, and under direct orders from an impatient Howard, the two tried again, succeeding this time in holding the ground despite counterattacks and heavy concentrated barrages of artillery. The fighting here on this and nearby hills in mid June was especially close and personal, combative and aggressive – often hand-to-hand and frequently continuing into the night.

It was here at the Wallis House on June 22 that Sherman first learned of Hood’s attack on Hooker’s Corps at the Kolb Farm House three miles south. Surprised by the attack, thinking Hood still at Brushy Mountain, Sherman was further confounded and angered by Hooker’s claim that the “entire Confederate army was in his front.” Hood’s corps had been quietly withdrawn from Brushy Mountain the night before to a point ten miles south on the Powder Springs Road – a major road approaching Marietta along a ridge from the southwest. Hooker’s lack of composure during this battle, and his effort later to lay the blame for any mishaps at Kolb’s Farm on General Howard’s Fourth Corps (part of a long-festering enmity dating back to Hooker’s criticism of Howard’s Eleventh Corps’ conduct at Chancellorsville in 1863) would be a factor later, when Sherman by-passed the more senior general, Hooker, and named Howard to command the Army of the Tennessee after McPherson’s death. Angered by what he considered Sherman’s double affront in this matter, Hooker would resign his post and leave the war.

Hood’s reputation at Kolb’s Farm was diminished with Johnston as had Hooker’s been with Sherman. Hood’s two-division attack was unauthorized by Johnston. The primary purpose for the displacement from Brushy Mountain was to keep pace with Sherman’s flanking movements, not to launch an attack. Hood’s effort by Stevenson’s and Hindman’s divisions gained some initial success but no permanent advantage. Hindman’s men, trapped in an artillery crossfire, suffered the majority of the 1,000 Confederate casualties. Hood claimed victory. Visiting the field the next morning, General Johnston knew otherwise.

The rains ended June 23. A hot sun quickly dried roads and fields, and U.S. Grant wired Sherman that he could maneuver freely now since there was no longer any danger of transfer of reinforcements from Robert E. Lee’s Eastern Theater forces to Johnston. Although eager to resume the “freedom” of past flanking maneuvers, Sherman would need several days staging time in preparation for the forays toward Atlanta.

Meanwhile Sherman reasoned, why not a serious assault on the mountain fortress? Surely the Confederates must be stretched thin somewhere along these miles of defenses from the mountain south to Smyrna. By June 23 plans were in progress for a major departure from Sherman’s usual flanking inclinations. The Battle of Kennesaw Mountain would be fought Monday, June 27, 1864.

Divisions from the Fifteenth Corps would attack a spur of Little Kennesaw at Burnt Hickory Road, and simultaneously a 12,000-man strike force from the Army of the Cumberland would hit a point two miles south near the Dallas Road. French’s division at the Kennesaw spur would absorb most of the blow near the Burnt Hickory Road, while Hardee would be called upon to turn back the larger attack at the Dallas Road. Each assault was to be preceded by an intense one-hour artillery barrage.

When the artillery fire lifted, Lieutenant Colonel Rigdon Barnhill’s 40th Illinois led the charge toward the mountain spur, ending with Barnhill’s death less than 30 feet from French’s entrenchments. Caught in a crossfire from nearby Little Kennesaw and French’s men directly ahead on the spur, and slowed by the tree branch entanglements prepared by the defenders, this effort by the Fifteenth Corps at the Burnt Hickory Road was over before noon. Sherman would later write Belle Barnhill, the widow, telling of her husband’s bravery and expressing regret that the body was too close to enemy defenses to recover the remains.

The assault near the Dallas Road was pursued with equal vigor. Occasionally individual soldiers, always too few in number, succeeded in overrunning the defenders and were quickly killed or captured. Musician Fife Major Allison Webber (86th Illinois) borrowed a Henry repeating rifle with 120 rounds of ammunition, volunteering to join the assault. Using the rapid fire of this repeater, Webber covered the rescue of the wounded and the construction of protective earthworks nearby, earning the Medal of Honor for his conduct.

By 11 o’clock, on Thomas’s front as well as on McPherson’s field of combat two miles north at the Burnt Hickory Road, the sound of gunfire gradually died away. The assault had failed – the result of a combination of tough Confederate resistance and extremely hot and humid weather. Some Union soldiers remained in defilade near Confederate trenches, being reinforced at nightfall sufficiently to hold the ground. There were no plans to renew the attack. No real advantage was gained anywhere on the 27th except Schofield’s capture of a Sandtown crossroads near Olley’s Creek ten miles southwest of the mountain. Sherman’s claims of 2,500 casualties at the principle points of attack at Kennesaw Mountain and Cheatham’s Hill (Thomas’s front) were probably low by half. The Confederates, protected by earthworks, reported their own casualties in the more believable range of 500 – 800 men. The Confederate figures seem more consistent with the maxim recorded in Union division commander Jacob Cox’s war diary: “one good man behind earthworks should prevail over four or five opponents advancing in the open without cover.”

With roads dried out, with sufficient supplies accumulated, and with the last units of McPherson’s Army of the Tennessee shifted from positions at Brushy Mountain and elsewhere for purposes of coordinating with and eventually replacing Schofield’s army in turning the Confederate left, Sherman abandoned his month-long focus on the battlefields around Kennesaw Mountain. He would now turn southward toward the Chattahoochee River and the prize of Atlanta.

Sherman’s activities meant that Johnston must abandon his strong positions at the mountain and retire southward to protect his railroad lifeline to Atlanta. What followed would be a race for the Chattahoochee with an opportunity, Sherman believed, to embarrass Johnston’s Confederates in the act of crossing the river. Instead he found the Rebels with new defenses along an east-to-west-running ridge just north of Smyrna; flanks anchored near Rottenwood Creek at the river on the east, and fish-hooked at the west on a hill two miles from Ruff’s Mill. At 4 p.m. on July 4, a column of six regiments from Dodge’s Sixteenth Corps led by Colonel E.F. Noyes (39th Ohio Infantry) attacked an advanced position near this angle, capturing the line and about 100 prisoners. Noyes himself was wounded, necessitating the amputation of a leg. Johnston abandoned the Smyrna position during the night and withdrew to the river.

What Sherman found next came to him as a total surprise: a six-mile bridgehead of defensive bunkers on the north side of the river: the powerful and unique “River Line.” Designed by General Francis A. Shoup (Johnston’s chief of artillery), constructed in less than two weeks by a labor force of nearly 1,000 slaves under Shoup’s personal supervision, the River Line provided the perfect shield for any river crossing Johnston might choose to make. Arrow-shaped log structures tightly packed with dirt each provided a platform and parapet for a company of riflemen supported by pairs of two-gun teams of artillery. These arrow-shaped mini-forts have come to be called “Shoupades.” The mini-forts and artillery positions were spaced at intervals along the battle line in such a way as to create interlocking fields of fire by rifle and cannon. The River Line today has the distinction of being truly a national one-of-a-kind Civil War defensive engineering marvel. Sherman, impressed by what he saw, chose not to test its strength, and shelved the plans to challenge the Confederate river crossing. Instead, he began a search for some places of his own to cross the river.

Using divisions from the Ohio and Cumberland armies to probe for such opportunities east near Roswell, successful division-size crossings were soon made at Sope Creek and at a nearby fish dam. Within days Sherman had corps-sized numbers on the Atlanta side of the Chattahoochee River. By July 8, the major portion of Sherman’s army was south of the river. Johnston must now abandon his River Line bridgehead north of the river and retire to the Atlanta defenses. McPherson’s Army of the Tennessee had been shifted to the east to cut the Augusta railroad to Atlanta thus blocking any possible reinforcement should such be attempted. Thomas’s Army of the Cumberland had followed the line of the Western and Atlantic Railroad and was now across the river near Peachtree Creek, while Schofield’s Army of the Ohio was soon shifted westward toward Ezra Church and Utoy Creek on the northwest side of Atlanta.

On July 16, 1864, John Bell Hood would be appointed to command the Confederate Army of Tennessee replacing Johnston. Aware of Hood’s aggressive inclinations, William T. Sherman must now adjust his Atlanta “chess game” to accommodate the fighting style of the new Confederate leader. He must now brace for the inevitable reckless assaults Hood was sure to bring his way.

On July 16, 1864, Sherman could not have believed he was still four major battles and six weeks away from the September capture of his prize, Atlanta.

Your gift today helps save 77 acres at Ringgold Gap, Rocky Face Ridge, and Kennesaw Mountain — where history was made — with an incredible $22-to-$1...

Related Battles

3,000

1,000