Germantown

Following the American defeat at the Battle of Brandywine in September, the British had occupied Philadelphia, the American capital. British General William Howe had divided his forces between Philadelphia and nearby Germantown. Howe had stationed two British brigades in the village, commanded by General James Grant, and Hessian troops under General Wilhelm von Knyphausen, totaling 9,000 men. George Washington, with the victories at Trenton and Princeton fresh in his mind, planned a similar double envelopment at Germantown. Washington’s army consisted of 8,000 Continentals and 3,000 militiamen.

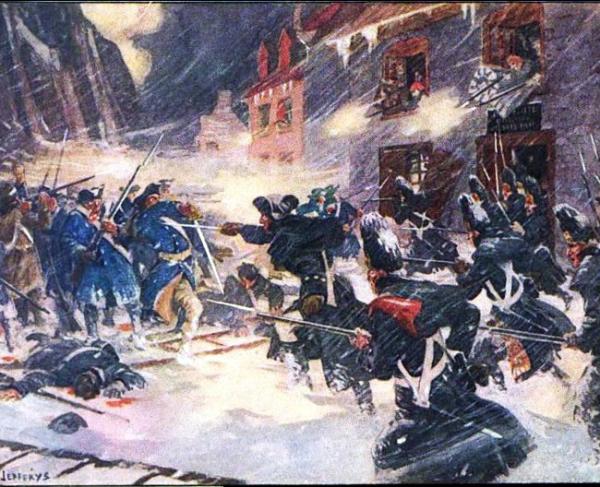

Washington launched his operation on the night of October 3/4, 1777. His plan, much like at Trenton, involved dividing his forces for a simultaneous attack at dawn. General John Sullivan would attack with the main force while General Nathaneal Greene attacked on the flank. The militia, under General William Smallwood, targeted the British extreme right and rear. Unfortunately for Washington, darkness and a heavy fog greatly delayed the advance, and the element of surprise was lost.

Sullivan’s column was the first to make contact, driving the British pickets off Mount Airy. The British were so shocked to find a large force of American soldiers that some were cut off from the main body; 120 men under British Col. Musgrave took shelter in the large stone house of Chief Justice Benjamin Chew: Cliveden. This fortified position would prove a thorn in the Americans’ side for the remainder of the battle, with numerous assaults being repulsed with heavy casualties. While the battle around Cliveden raged, Sullivan pushed his men towards the British center.

On Sullivan’s left flank, General Anthony Wayne’s brigade became separated in the fog. Sullivan’s men were also beginning to run low on ammunition, causing their fire to slacken. The separation, combined with the lack of fire from their comrades, and the commotion of the attack on Cliveden behind them, convinced Wayne’s men that they were cut off, causing them to withdraw. Luckily, Greene’s column arrived in time to engage the British before they could rout Wayne. Unfortunately, one of Greene’s brigades, under General Adam Stephen, also became lost in the fog, mistook Wayne’s men for the British, and opened fire. Wayne’s men returned fire. The resulting firefight caused both units to break and flee the field.

Meanwhile, Greene’s left, under General Alexander McDougall, came under heavy fire and, despite inflicting heavy casualties, was forced to withdraw. In Greene’s center the 9th Virginia Regiment, convinced that victory was within grasp, launched a daring charge into the British lines, breaking through and even taking prisoners. Unfortunately, the regiment was caught by two British reserve brigades under General Cornwallis, surrounded, and forced to surrender en masse. Greene, with his men faltering and learning of Sullivan’s retreat, ordered a withdraw.

The British hotly pursued the retreating Americans, routing a number of units. Only the steadfastness of Greene and Wayne’s men and artillery, and the coming of darkness, prevented a disaster. American losses were more than 700, with another 400 captured; the British lost more than 500. While the battle was a British victory, the determination of the Continental Army still impressed many Europeans, especially the French. The British would only hold Philadelphia for a year, withdrawing to New York in June of 1778.