The Kansas-Nebraska Act

Described by historians as the most consequential piece of legislation ever passed, the Kansas-Nebraska Act of 1854 represented a pivotal moment in American history which forever changed American politics and unequivocally contributed to the coming of the American Civil War.

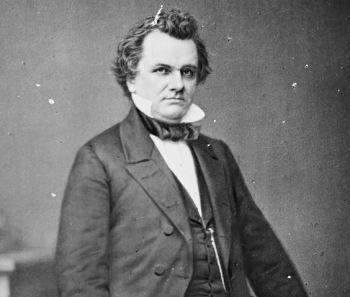

By 1853 discontent over President Franklin Pierce’s patronage allotement caused the Democrats to lose support among their constituents. In order to save the party from ruin, the Democrats needed something that would rally their base behind it and the best way to achieve this was to provoke opposition from its rival party—the Whigs. However, Pierce did not have any domestic policy that would serve this purpose, so Democratic Senator Stephen Douglas filled that void. Douglas developed a three-pronged western development program to drum up conflict with the Whigs. The first part was the formal organization of the territory west of Iowa and Missouri. The second part was enacting a homestead law that gave free land to settlers. The final part was the construction of a transcontinental railroad with federal land grants, which of course, would run through his home state of Illinois. Douglas’s top priority was the preservation of the Democratic Party not the preservation of the Union. It was a common trend among antebellum politicians to make decisions that would achieve short term partisan advantages with little concern for the long-term consequences these decisions would have on the health and preservation of the Union.

It is important to note that the pressure to organize the land west of Missouri and Iowa did not come from land-hungry southern slaveholders or southern politicians wanting to extend slavery, rather it came from two northern sources. The first source were farmers seeking cheap land, as they could not gain a title for their settlements until Congress organized the territorial government. The second source was railroad promoters (including Stephen Douglas) because the construction of a continental railroad required Congress to survey the land into sections to subsidize to the railroad companies. Thus, northern politicians faced pressure from their constituents to organize this territory although many wanted the continuation of the Missouri Compromise restriction to these lands, which restricted slavery above the 36°30’ parallel, Missouri’s southern border.

In order to execute his plan, Douglas first needed to organize the territory west of Iowa and Missouri (Nebraska and Kansas). Southern Democrat support was necessary for Douglas’s plan, yet many southerners despised the Missouri Compromise and the limitations it placed on slavery, which required the construction of a territorial organization bill that repealed the Missouri Compromise. This bill became known as the Kansas-Nebraska Act. The Kansas-Nebraska Act stipulated that the territory west of Missouri and Iowa would be organized into two territories and that “all questions pertaining to slavery in the territories and in the new states to be formed therein are to be left to the people residing therein, through the appropriate representatives.” This principle quoted in the bill is known as popular sovereignty. Popular sovereignty was first introduced as a potential solution during the crisis over organizing the territory gained through the Mexican Cession, but it failed to gain headway among politicians. In principle, popular sovereignty is neither pro-slavery nor anti-slavery as it is the citizens in the specific territories who decide if slavery should be allowed in these places, not Congress. However, the Kansas-Nebraska Act in itself was a pro-southern piece of legislation because it repealed the Missouri Compromise, thus opening up the potential for slavery to exist in the unorganized territories of the Louisiana Purchase, which was impossible under the Missouri Compromise. Despite Douglas’s understanding that the North would be furious with the repeal of the Missouri Compromise restriction, Douglas proceeded with the Kansas-Nebraska Act because he wrongfully assumed that slavery would never exist in those territories and he needed to garner southern support for his bill.

The Kansas-Nebraska Act forced the repealing of the Missouri Compromise, which infuriated northerners. However, the Kansas-Nebraska Act easily passed the Senate on March 4, 1854 by a vote of 37 to 14 with southern Whigs voting in favor of the bill—even if southern Whigs voted against the bill, it still would have passed the Senate. However, in the House of Representatives some northern Democrats caved to this political pressure from their constituents and voted against the bill. Despite this, on May 22, 1854, the bill passed the House by a much closer vote of 113 to 100 with northern Democrats split right down the middle, 44 voted in favor, 44 voted against. Additionally, 13 out of the 24 southern Whigs voting in favor (four abstained), enough to tie the House vote if they voted against. President Pierce signed this bill into law on May 30, 1854 and the massive political fallout that ensured had immediate and enduring consequences.

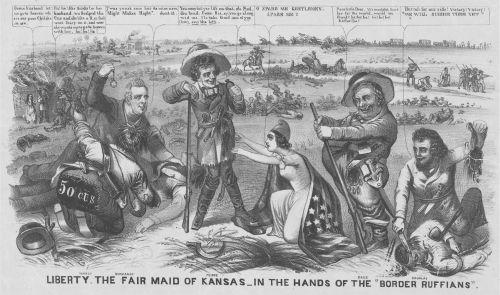

Many northerners view the passage of the Kansas-Nebraska Act as evidence of the slave power’s hostility to the North and the damaging effects it had on northern interests. Consequently, the Democratic Party faced significant backlash from its northern wing. In the congressional elections of 1854 and 1855, the Democrats lost 66 out of the 91 seats they held prior to the passage of this bill and of the 44 northern Democrat Representatives who voted in favor of this bill, only seven won reelection. The alienation of northern Democrats from the southern wing of the party was hardly the solidification and unification Pierce and Douglas intended to bring about through this legislation. The fracture between northern and southern Democrats only grew with Bleeding Kansas and the crisis over the Lecompton Constitution, two additional direct consequences of this bill. Additionally, the negative reaction to this bill destroyed Pierce’s ambitious plan for additional territorial expansion—the Gadsden Purchase almost failed in Congress and ruined Pierce’s hope of annexing slaveholding Cuba into the United States.

However, one of the most significant and lasting effects the Kansas-Nebraska Act had on the American political system was the formation of the Republican Party. The Kansas-Nebraska Act directly led to the creation of the Republican Party. In 1854, the Whig Party was essentially on life support as Pierce’s election, Henry Clay’s death and the formation of “Conscious” and “Cotton” factions served to be significant blows to the party’s unification and message. However, the southern Whig support for the Kansas-Nebraska Act represents the final death blow to the party. The bill would have failed if southern Whigs voted against it and northern Whigs viewed their support as a betrayal to Whig principles. The final sectional split between northern and southern Whigs occurred when anti-slavery northern Whigs left the party over the perceived betrayal by southern Whigs and joined ranks with independent free soilers to join a new broad anti-slavery party that opposed the Kansas-Nebraska Act, slavery’s extension and the slave power’s control of politics—the Republican Party.

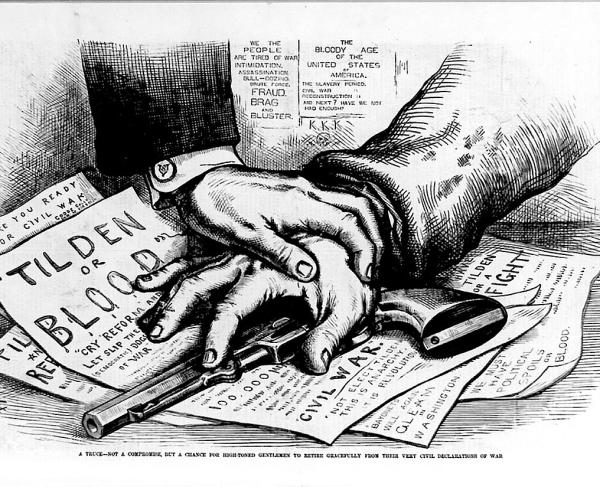

As the 1850s progressed, Republicans continued to build their base with each perceived aggression from the slave power, including Bleeding Kansas and the Lecompton Crisis, and became a significant threat to the Democrat Party. The split between northern and southern Democrats would continue to grow throughout the 1850s to the point where the Democratic party intentionally ran a northern candidate (Stephen Douglas) and a southern candidate (Vice President John C. Breckenridge) in the presidential election of 1860. The consolidation of Republican power and the fracturing of the alliance between northern and southern Democrats led to Abraham Lincoln’s Election in 1860, triggering the secession of the lower south states. While the Kansas-Nebraska Act in no way directly caused the Civil War, its existence and the political consequences that arose from it remain essential to the coming of the Civil War and had lasting effects on the United States.