"Mount Up!"

The Gettysburg Campaign is usually considered to be the bellwether campaign of the American Civil War. Many critical events occurred during the Campaign, but few were more important than the maturation of the Army of the Potomac’s Cavalry Corps. Until the spring of 1863, the Army of Northern Virginia’s mounted arm literally rode rings around its Union counterpart. In February 1863, Maj. Gen. Joseph Hooker, the newly appointed commander of the Army of the Potomac, ordered the consolidation of the army’s mounted forces into a single corps for the first time. Those cohesive mounted forces, under competent leadership, could now face their Confederate counterparts on something approaching even terms. That maturation process reached its pinnacle during the Gettysburg Campaign.

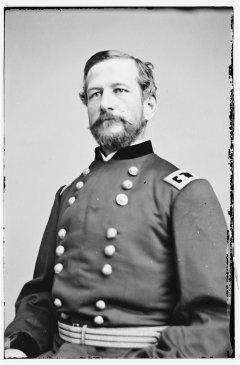

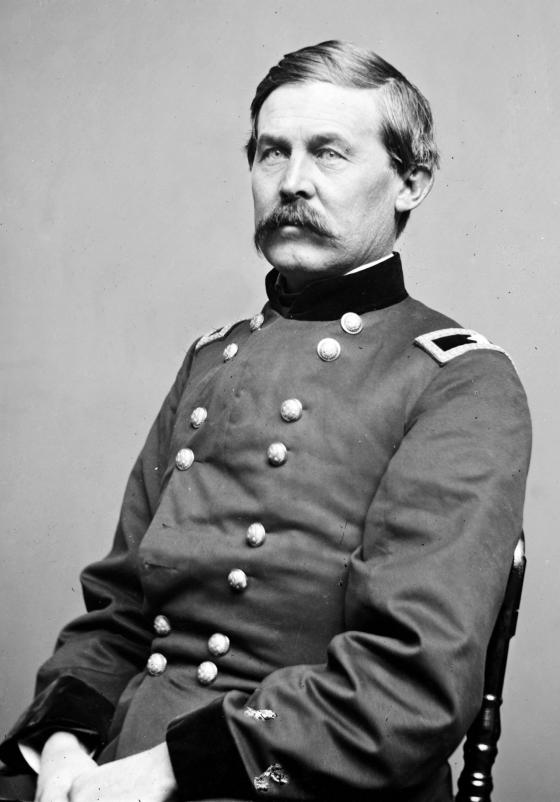

On May 15, 1863, Maj. Gen. George Stoneman, the commander of the Army of the Potomac’s Cavalry Corps, took medical leave to seek treatment for a terrible case of hemorrhoids that made every moment bouncing in the saddle a living hell. Brig. Gen. Alfred Pleasonton, his senior division commander, assumed de facto command of the Cavalry Corps. Thirty-nine-year-old Pleasonton, a member of the West Point Class of 1844, had spent his entire military career in the dragoons. He became a division commander in the fall of 1862. Pleasonton had a sharp eye for talent, but was an ambitious intriguer not known for his courage on the battlefield. In spite of these less than attractive traits, Pleasonton left an indelible mark on the Army of the Potomac’s Cavalry Corps that began with the Gettysburg Campaign.

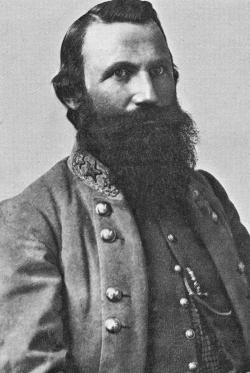

Following the crushing defeat of Hooker’s army at Chancellorsville at the beginning of May 1863, the Confederate high command decided to take the war to the North, electing to invade Pennsylvania to gain a respite for Virginia’s farmers from the harsh realities of the war. Gen. Robert E. Lee’s Army of Northern Virginia began concentrating in Culpeper County in preparation for the invasion. Seven full brigades of Southern horse gathered near Brandy Station, a stop on the Orange & Alexandria Railroad near Culpeper. Their commander, 30-year-old Maj. Gen. James Ewell Brown “Jeb” Stuart, had already earned a reputation as a bold and dashing cavalier. The Virginia-born West Pointer possessed a valuable gift for scouting, screening and reconnaissance, and had already made himself indispensable to Lee as the eyes and ears of the army.

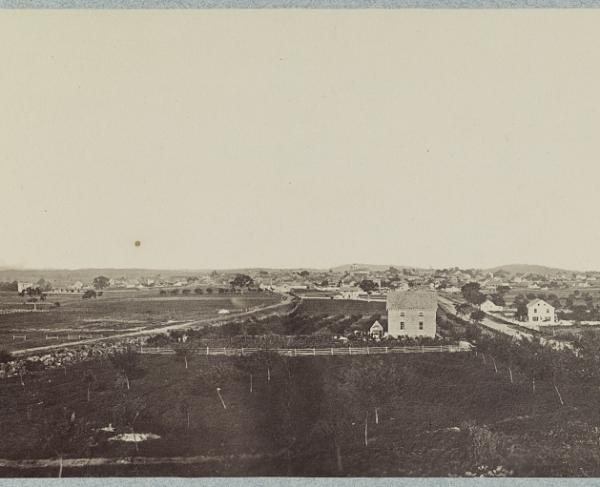

As May turned to June, Stuart held a series of grand reviews of his horsemen, culminating with a review by Robert E. Lee himself on June 8, 1863. Lee inspected nearly 12,000 gray-clad horsemen and several battalions of horse artillery on the grounds of John Minor Botts’ farm just outside the town of Culpeper. The Army of Northern Virginia’s infantry was scheduled to march north the next day, with Stuart’s horsemen leading the way, scouting and screening the infantry’s advance.

Little did Stuart realize that as General Lee inspected his troops, 9,000 Federal cavalrymen lay just across the Rappahannock River preparing to attack the following morning. Joseph Hooker, suspicious of the large build-up of Confederate cavalry in Culpeper County, ordered Pleasonton to take the entire Cavalry Corps of the Army of the Potomac out and either disperse or destroy them. Pleasonton took three divisions of horsemen, two brigades of horse artillery and two brigades of selected infantry (numbering 3,000 men), and prepared to pounce on the Confederate cavalry on the morning of June 9, 1863.

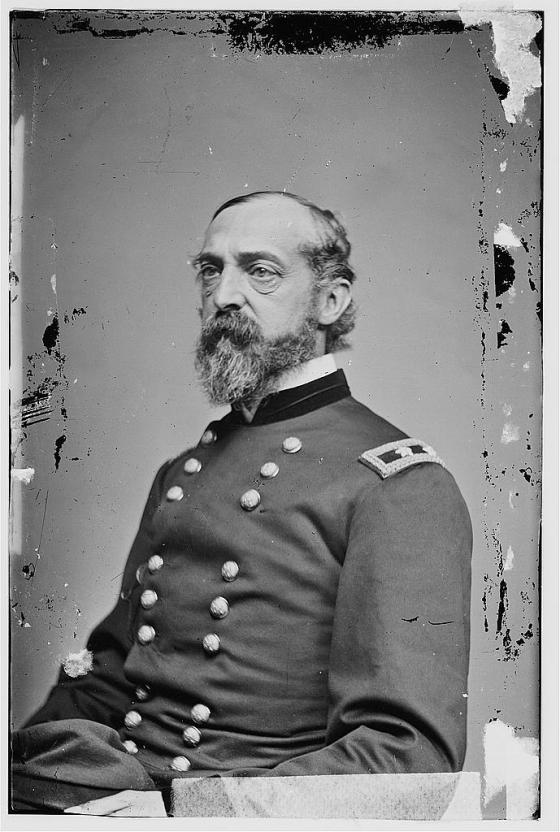

Pleasonton formulated an excellent plan for his foray across the river. His senior division commander, 37-year old Brig. Gen. John Buford, a native Kentuckian who was a member of the West Point Class of 1848 and a career dragoon, would command the right wing of the operation, including his own First Division and a brigade of infantry. Pennsylvanian Brig. Gen. David M. Gregg would command the left wing, which included the other infantry brigade, Gregg’s Second Division and Col. Alfred N. Duffíe’s Third Division. In addition, several batteries of Federal horse artillery would accompany the columns, adding firepower to the already potent Union force.

Under Pleasonton’s plan, Buford’s men would cross the Rappahannock at Beverly Ford, while Gregg’s crossed at Kelly’s Ford. Buford would then ride to Brandy Station, where they would rendezvous with Gregg’s Second Division. Duffíe, a deserter from the French Army, commanded a small division that would also cross at Kelly’s Ford, then proceed to the small town of Stevensburg to secure the flank east of Culpeper. Buford and Gregg would then push for Culpeper, where they would fall upon Stuart’s unsuspecting forces and destroy them. In case Confederate infantry appeared, the Federal infantry would support the attacks. Pleasonton had his men pack three days’ rations because he intended to chase the routed Confederates. Careful timing was required to pull off the attack as planned.

The Battle of Brandy Station

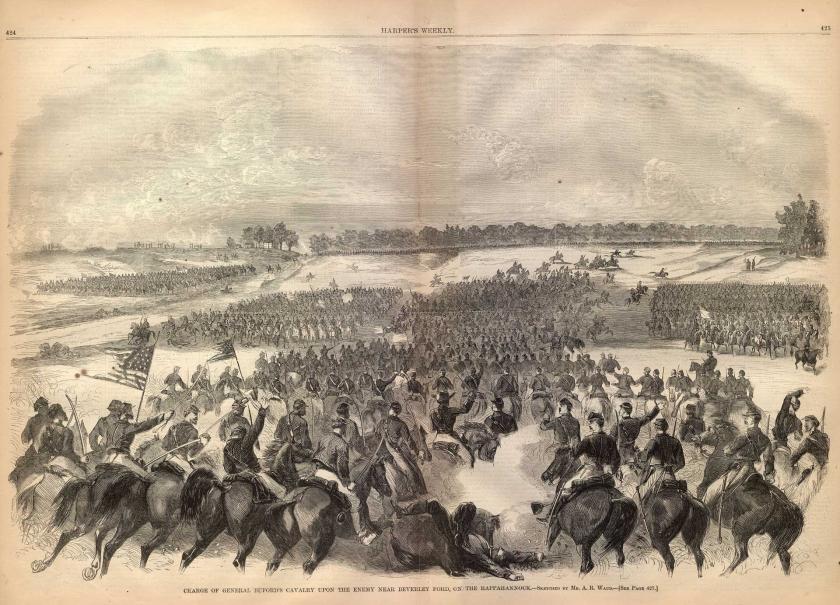

Buford’s veteran division began crossing the Rappahannock at Beverly’s Ford about 5:00 a.m. on June 9. The division advanced in columns of four, with Col. Benjamin F. “Grimes” Davis’ brigade leading the way. Davis, a Mississippi-born West Pointer, was known as a martinet, but he was a fine officer. The blue-clad horsemen emerged from the early morning mists to find pickets of Capt. Bruce Gibson’s company of the 6th Virginia Cavalry of Brig. Gen. William E. “Grumble” Jones’ brigade just on the other side of the river. Gibson’s pickets made enough of a stand to allow time for word of the advance of a large Union force to reach Jones, who quickly got his troopers into the saddle and on the move to meet the threat. Davis, far in advance of his brigade, was killed instantly during an encounter with an officer of the 12th Virginia Cavalry, and his leaderless brigade fell back. Jones deployed his dismounted troopers to defend most of the Confederate horse artillery, posted on a ridge line above Beverly’s Ford near St. James Church.

Learning that Davis had been killed, Buford splashed across the river and ordered five companies of the 6th Pennsylvania Cavalry to charge the artillery. The Pennsylvanians dashed at the guns, losing their commanding officer, Maj. Robert Morris, Jr., who had his horse shot out from under him midway across the wide field. The Keystone Staters reached the barrels of the guns before being repulsed. By this time, troopers of Brig. Gen. Wade Hampton’s fine brigade of Southern cavalry had arrived to reinforce Jones. The battle devolved into a standoff, as Buford’s men made numerous unsuccessful dismounted attacks against a stone wall held in force by troopers of Brig. Gen. William H. F. “Rooney” Lee’s brigade. Rooney Lee, second son of Robert E. Lee, was not a West Pointer; he was a Harvard-trained lawyer and gentleman planter, but he had demonstrated competence in commanding cavalry. The 6th Pennsylvania Cavalry, this time supported by troopers of the 6th U.S. Cavalry, made another determined charge at Lee’s position along the stone wall, again taking heavy losses. Buford and his troopers fought alone for nearly six long hours that morning.

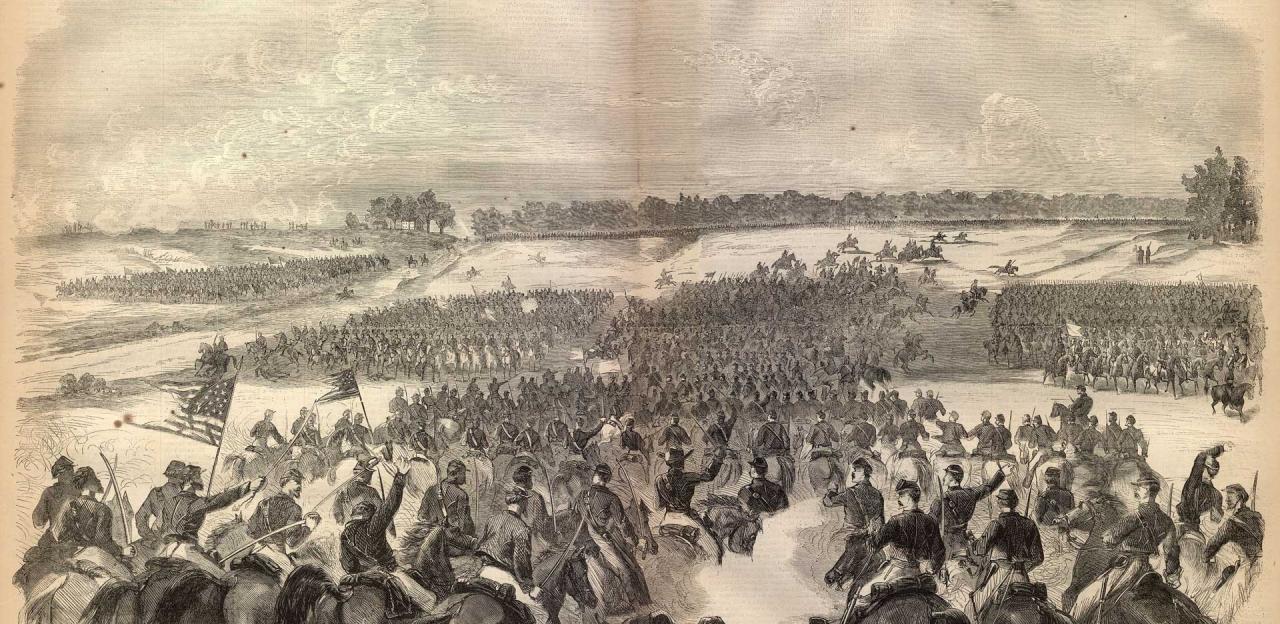

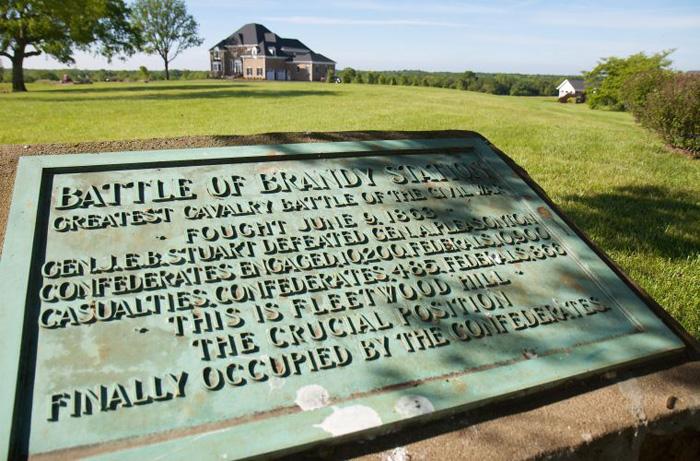

In the meantime, David Gregg’s Second Division made its way across the Rappahannock at Kelly’s Ford and finally headed toward Brandy Station. The lead elements of Gregg’s column came within view of the high ground at Fleetwood Hill and saw that the area was largely undefended, but for the tent fly of Jeb Stuart’s headquarters. One of Stuart’s staff officers spotted the Federal advance, grabbed a single cannon, and sent back to get more ammunition. The lone gun belched fire upon the advancing Federals, who slowed to deploy into line of battle. Stuart, now aware of his critical situation, called for Jones’ and Hampton’s brigades, which galloped several miles from the vicinity of St. James Church to meet the Federals as they advanced on Fleetwood Hill.

There, in the fields around Fleetwood Hill, played out one of the great romantic dramas of the American Civil War. For hours, mounted charges and countercharges took place, as four full brigades clashed in mounted, hand-to-hand combat. Federal troopers nearly seized Fleetwood Hill and Stuart’s headquarters before finally being driven off.

The focus of the fighting then shifted back to Buford’s troopers. After driving Rooney Lee’s men from the stone wall, Buford sent his Reserve Brigade, consisting of the U.S. Regular cavalry and the 6th Pennsylvania Cavalry, up Yew Ridge, the northern extension of Fleetwood Hill. The Yankee horsemen gained the crest of the hill before again slamming into Rooney Lee’s men, and another melee of hand-to-hand fighting broke out. Rooney Lee fenced with Capt. Wesley Merritt, the commander of the 2nd U. S. Cavalry, and suffered a serious saber wound. Lee’s troopers slowly drove Buford’s men back.

In the interim, Duffíe’s division had been stopped dead in its tracks by two regiments of Confederate cavalry at Stevensburg, not far from Kelly’s Ford. The Frenchman’s troopers killed Lt. Col. Frank Hampton of the 2nd South Carolina Cavalry and then routed the South Carolinians and the 4th Virginia Cavalry, which had been sent to their support. The 2nd South Carolina fell back to a strong defensive position and was only driven off after a Union artillery shell took the foot of Col. Matthew C. Butler, the commander of the Palmetto Staters. Duffíe’s troopers finally pushed their way through and headed toward the sound of the guns at Fleetwood Hill, arriving as Gregg’s men were beginning to withdraw.

By now, it was nearly 5:00 p.m., and Pleasonton had seen enough. He ordered his men to withdraw, and they did, slowly and in an orderly fashion, fighting as they fell back. Stuart was perfectly happy to let them go. Both sides suffered significant casualties in a battle that had lasted 13 long hours. The Yankee troopers had given as well as they had gotten, and if the Confederates needed proof that the tide had turned, Brandy Station amply provided the evidence. At the end of the day, Stuart’s troopers held the field. They had prevented Pleasonton’s men from achieving any of their objectives, and they had survived the unpleasant surprise delivered by the Federal horsemen. The great Battle of Brandy Station was over.

Aldie, Middleburg and Upperville

The Army of Northern Virginia’s infantry marched the next day, June 10. Stuart’s diligent horsemen screened their advance, keeping Pleasonton’s aggressive troopers away from the main body of Lee’s army. In the meantime, Pleasonton reorganized the Cavalry Corps. Duffíe’s division was absorbed into Gregg’s division, and the Frenchman reverted to command of the 1st Rhode Island Cavalry. He was not competent to command a division, and also did not have the requisite rank for the position.

A full day of fighting took place at Aldie on June 17, as Stuart prevented the Federals from pushing through Aldie Gap in the Bull Run Mountains. Duffíe’s Rhode Islanders were cut to pieces when Pleasonton sent the single regiment alone and unsupported behind enemy lines, leading to Duffíe’s relief. He never again commanded cavalry in the Army of the Potomac. Two days later, Gregg’s division fought Stuart’s horsemen a few miles west at Middleburg, and again, Stuart’s men prevented Gregg’s troopers from finding the main body of Lee’s army.

On June 21, at Upperville, near the mouth of Ashby’s Gap through the Blue Ridge, Stuart’s horsemen suffered their first battlefield defeat at the hands of the Federal cavalry. Pressed by Buford’s troopers on their flank and by Brig. Gen. Judson Kilpatrick’s brigade, supported by a brigade of V Corps infantry, at its front, Stuart’s vaunted horsemen were routed and driven from the field for the first time in the war. They fell back on Lt. Gen. James Longstreet’s infantry, passing down the Shenandoah Valley just on the other side of the Blue Ridge. However, Pleasonton did not press his advantage, and never did find the main body of Lee’s army, which was spread out in the Valley just on the other side of the Blue Ridge. Stuart successfully traded time for space, however, and conducted a masterful delaying action and demonstrated his brilliance at scouting and screening.

A second reorganization of the Army of the Potomac’s Cavalry Corps took place at the end of June. A third division of cavalry assigned to the defenses of Washington, D.C., joined the Cavalry Corps, and Pleasonton placed Kilpatrick in command of it. He then arranged for three young officers, Wesley Merritt, George A. Custer and Elon J. Farnsworth, to be promoted from captain to brigadier general. Merritt took command of Buford’s Reserve Brigade, while Custer and Farnsworth assumed command of the two brigades of Kilpatrick’s Third Division.

Stuart’s Ride

Stuart received orders to take three brigades of cavalry on a ride. If he found that the Army of the Potomac had moved, and that the cavalry forces remaining with the Army of Northern Virginia could safely hold the mountain passes, Stuart was to move east of South Mountain, then cross the Potomac River. He was to gather supplies for the use of the army, create chaos where possible and then link up with Lt. Gen. Richard S. Ewell’s Second Corps of the Army of Northern Virginia, which would be operating in south-central Pennsylvania.

Stuart rode out on June 25 and fell behind schedule immediately. When the head of his column emerged from the mouth of Glasscock’s Gap, near Haymarket, he found Maj. Gen. Winfield S. Hancock’s entire Federal II Corps spread out in the valley below. After some desultory skirmishing, Stuart broke off and withdrew. He then passed around the Union army to the south, and had an unexpected encounter with Federal cavalry near Fairfax Court House. After plundering the Federal supply depot there, his troopers crossed the Potomac River at Rowser’s Ford and headed north. They captured a train of 150 wagons near Rockville, Md., on June 28, and skirmished with a force of feisty Delaware cavalry at Westminster, Md., on June 29.

The next day Stuart spent an entire day engaged in combat at Hanover, Pa., with Kilpatrick’s Third Division. Hanover witnessed one of the few instances of mounted street fighting, with charges and countercharges up and down the streets of the town. Stuart himself narrowly escaped capture, leaping his horse over a wide ditch to make his escape. After hard fighting that featured the combat debut of newly promoted Union Brig. Gen. George A. Custer, assigned to command a brigade of Michigan horse soldiers, Stuart broke off and withdrew, heading toward York, Pa., where he hoped to find Confederate infantry.

Stuart arrived near York and learned that the Southern infantry had left the day before. Unsure what to do next, but expecting to find the rest of the Ewell’s men in the vicinity of Carlisle, Pa., Stuart marched there with the brigades of Brig. Gen. Fitzhugh Lee and John R. Chambliss, Jr. (commanding the wounded Rooney Lee’s brigade).

Arriving at Carlisle about 6:00 p.m. on July 1, Stuart was shocked to find not Confederate infantry, but Union infantry instead. Stuart shelled the town when the Federal commander refused to surrender, and skirmishing continued for a number of hours. The Confederates set the buildings of the Carlisle Barracks (an important Federal military base) and the town gas works ablaze, lighting the night sky with an eerie glow. When one of his staff officers finally reported that the Confederate army had concentrated at Gettysburg and was fighting there, Stuart withdrew and turned toward Gettysburg, arriving there mid-afternoon on July 2.

Buford’s Stand, July 1

While Stuart’s command went on its ride, Buford’s division made its way north, crossing the Potomac River near Leesburg, Va. Buford marched through Maryland and on into Pennsylvania, arriving at the Monterey Pass on June 29. After a brief skirmish with Mississippi infantry of Maj. Gen. Henry Heth’s division at Fairfield on the morning of June 30, Buford marched to Emmitsburg, Md., met briefly with Maj. Gen. John F. Reynolds (who commanded the three advance corps of the Army of the Potomac) and then marched the remaining 13 miles to Gettysburg. While just south of town, Buford sent a squadron ahead to investigate any Confederate infantry in the area of the Chambersburg Pike, but a reconnaissance mission from Brig. Gen. James J. Pettigrew’s brigade was already withdrawing to the west. The head of Buford’s column entered town about noon and marched out Washington Street to the Chambersburg Pike. Buford recognized the good defensive ground to the south and east of the town and determined to defend it.

Buford’s brigades moved two miles west of town to McPherson’s Ridge, and Buford then spent the night preparing his defense of the town. If attacked, he would conduct a classic, textbook example of a covering force action, trading ground for time until the Union infantry could come up.

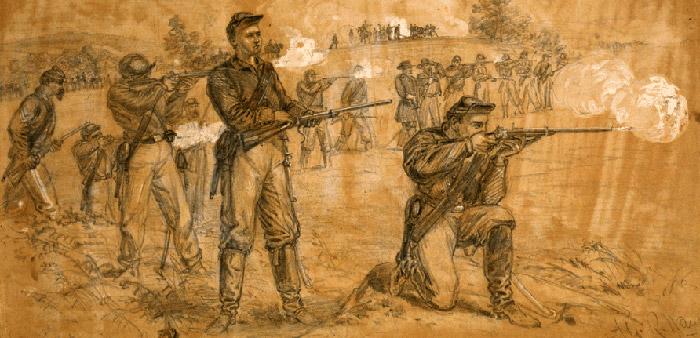

Buford established an early warning system by deploying videttes, or mounted sentries, farther to the west. Those pickets would give word of any Confederate advance and then fall back to prepared positions until they finally reached the main line on McPherson’s Ridge. Two brigades, nearly 3,000 men, covered a front seven miles long. It was a daunting task. Shortly after 7:00 a.m. on July 1, the head of Maj. Gen. Henry Heth’s Division appeared, in the van of Lt. Gen. A.P. Hill’s Third Corps of the Army of Northern Virginia, marching east on the Chambersburg Pike. Lt. Marcellus Jones of the 8th Illinois Cavalry borrowed a carbine, rested it on a fence post, and squeezed off a shot that hit nothing. However, the sound of the weapon sent up the alarm, and the Confederates halted and deployed skirmishers. When they resumed their advance, Heth’s skirmishers faced stout resistance from the dismounted troopers of Col. William Gamble’s brigade. Gamble’s troopers fell back to Herr Ridge and finally to McPherson’s Ridge, fighting hard and fooling the Confederates into believing that they faced infantry and not dismounted cavalry.

Buford’s men stood and fought on McPherson’s Ridge against Heth, who had formed a line of battle at Herr’s Ridge. It was now about 9:30 a.m., and the outnumbered Buford was getting worried. Just then, Reynolds and his staff arrived. After conferring with Buford, Reynolds spurred off to bring up the Army of the Potomac’s I Corps, which double-quicked cross-country to save time. The blue infantry arrived just as Gamble’s men were running out of ammunition and being pressed on both flanks. Buford had bought time for the Army of the Potomac to arrive. That afternoon, Gamble’s men made another stand on Seminary Ridge, helping to hold the Confederate infantry back long enough for the routed I Corps to make its escape. These dismounted horsemen had proven, once and for all, that the Union cavalry was a force to be reckoned with.

The next day, Buford’s two brigades were pulled from the line and sent to Westminster, Md., to guard lines of supply. They had faced a heavy task, and they had proven they were equal to the challenge.

July 2-3, 1863

In the early afternoon of July 2, Gregg’s division arrived in the vicinity of Gettysburg from Hanover. His men engaged Confederate infantry at Brinkerhoff’s Ridge, disallowing a brigade of veteran soldiers from participating in the Southern assaults on Culp’s Hill and East Cemetery Hill that night. They did a superb job of protecting the Union right flank.

In the meantime, Kilpatrick’s Third Division, at Hunterstown, had another encounter with Hampton’s cavalry. Hampton’s brigade was escorting the captured wagons to Gettysburg. In a classic example of a meeting engagement, a sharp fight broke out, featuring a mounted charge led by Custer himself. Custer’s horse was shot out from under him, and only good luck and the courage of his orderly prevented him from being captured. As darkness fell, the fighting petered out, and Kilpatrick went to take up a position on the Federal flank.

The next morning, recognizing the importance of the intersection of the Hanover and Low Dutch Roads – the Low Dutch Road being a direct route to the rear of the Union center – Gregg decided to strongly picket it. With his two brigades, Gregg deployed a long, thin line. Col. John B. McIntosh’s men covered the intersection, while Col. J. I. Gregg’s men connected with Union infantry on Wolf’s Hill. McIntosh’s men relieved Custer’s brigade, who began moving out. However, Gregg persuaded Custer, who was not under his command, to stay. Just then, Stuart’s command, which had arrived on nearby Cress Ridge, fired four artillery shells and tried to flush out the Union cavalry, signaling the beginning of fighting at East Cavalry Field.

Custer agreed to stay, and McIntosh’s men deployed. Before long, a heavy dismounted engagement raged in the fields around the John Rummell farm. Stuart’s command took heavy casualties in this engagement, and he sent Chambliss’ brigade forward in a mounted charge. Gregg responded by sending the 7th Michigan Cavalry, with Custer leading them, forward in a mounted charge that stopped the Confederate assault dead in its tracks. The Southerners fell back, and Stuart ordered a mounted countercharge by the brigades of Brig. Gens. Fitzhugh Lee and Wade Hampton.

The Southern horsemen deployed into line of battle, slowly marching, the blades of their sabers glinting in the bright afternoon sun. They charged, headed straight for Union artillery blasting away at them. Gregg again ordered one of Custer’s units, the 1st Michigan Cavalry, to charge, and, with Custer at their head crying, “Come on you Wolverines!” their charge split the Confederate line in two. Units of McIntosh’s brigade and elements of the 5th, 6th and 7th Michigan Cavalry regiments joined in, attacking the flanks of Stuart’s charging lines, and the confused Confederates broke and fell back. Taking more heavy losses, Stuart abandoned his quest to reach the intersection of the Hanover and Low Dutch Roads. The fight for East Cavalry Field was over.

Another drama played out on the main battlefield at Gettysburg, six or seven miles away. Kilpatrick had received orders to operate on the Confederate right flank, so he sent elements of Brig. Gen. Elon J. Farnsworth’s brigade forward. After several hours of dismounted skirmishing, Kilpatrick ordered Farnsworth to make a mounted charge. His protests denied, Farnsworth led 255 officers and men of the 1st Vermont Cavalry forward, charging the Confederate infantry and then headed for two batteries of artillery deployed on a ridge behind. In a scene akin to the fabled “Charge of the Light Brigade,” Farnsworth’s men were repulsed and the young Illinoisan, who had worn a general’s star only since June 28, was killed at the head of his men. The charge accomplished little but the needless death of a promising young officer.

In the meantime, Brig. Gen. Wesley Merritt’s Reserve Brigade of Buford’s division came up from Emmitsburg and engaged Confederate cavalry and infantry along the Emmitsburg Road. Some of Merritt’s Regulars made a mounted charge that briefly made its way around Lee’s far right flank, but their attack was unsupported and the Regulars fell back. Dismounted skirmishing continued until dark. Had these attacks been properly coordinated, they might have accomplished something. However, disjointed and unsupported, they did little.

Merritt had earlier detached one of his regiments, the 6th U.S. Cavalry, and sent it about 10 miles west to Fairfield, where Merritt was told a large Confederate wagon train ripe for the picking would be found. Instead, the regiment found the brigade of Grumble Jones, and after a short but sharp fight, the Regulars were repulsed with heavy losses, including the severe wounding of their commander, Maj. Samuel H. Starr. Again, a single regiment, unsupported and operating behind enemy lines, had little hope of success, and another opportunity was lost.

The Retreat and Pursuit of Lee’s Army

The Battle of Gettysburg ended at dark on July 3. Lee’s army began its retreat on the evening of July 4, heading toward the Potomac River crossings near Williamsport, Md. However, it began raining when the battle ended, and the heavy rains continued for several days, causing the Potomac to rise to flood stage, meaning it could not be forded. A force of marauding Federal cavalry destroyed the unguarded pontoon bridge across the river at Falling Waters, meaning that Lee would have to wait until the river level dropped to cross. The task of holding off the Federals fell upon Stuart’s cavalry.

Brig. Gen. John D. Imboden’s brigade of cavalry drew the task of escorting a 17-mile-long wagon train filled with wounded men to Williamsport, and Imboden handled the task superbly, delivering most of the wagons to the river crossing in spite of harassing Federal cavalry nipping at the edges and rear of the column. Imboden would have to defend the town until the river could be forded, and he faced a tremendous challenge.

The Union and Confederate cavalry clashed almost every day for more than a week. Kilpatrick’s division, joined by one of Gregg’s brigades, fought an engagement against Southern cavalry at the Monterey Pass in a blinding rainstorm on the night of July 4, finally breaking through and capturing some 250 Confederate ambulances and wagons and approximately 1,300 soldiers and teamsters. The next day, at Smithsburg, Md., Kilpatrick’s troopers skirmished with Stuart’s men before moving on to Boonsboro.

July 6 was the day of decision. Imboden, commanding his cavalry brigade and a scratch force of walking wounded and teamsters, held off a day’s worth of determined attacks by Buford’s division at Williamsport, while Stuart’s men defeated Kilpatrick’s division at Hagerstown. These twin victories by Stuart meant that Lee’s path to the Potomac River was kept open for use by his army. The Federal cavalry had failed, and it would not again have the opportunity to interdict the retreat of the Southern army. Had Buford and Kilpatrick succeeded, they would have forced Lee to fight the Federals on ground of their choosing.

On July 8, Stuart attacked Buford’s troopers at Boonsboro, hoping to prevent the Federals from seizing the initiative. In a full day of brutal combat, the Union troopers held off Stuart’s thrusts, forcing the Army of the Potomac to commit infantry and artillery to the fight. However, Stuart’s gambit worked, and the Army of Northern Virginia retained the initiative.

On July 10, Buford’s troopers again met Stuart near Funkstown in a large engagement that eventually involved both Union and Confederate infantry. The Federals won this fight, briefly offering Maj. Gen. George Gordon Meade’s Army of the Potomac an opportunity to split the Army of Northern Virginia in twain, but the opportunity slipped away, and the last chance for the Army of the Potomac to seize the initiative evaporated.

By July 12, Robert E. Lee’s engineers had laid out and constructed a stout defensive position along the north bank of the Potomac, and Lee ordered Stuart’s weary troopers to step aside and take up a position along the flanks. After two days of indecisive skirmishing, Meade decided to attack with the entire army on the morning of July 14.

However, by the night of the 13th, the river had dropped enough to be fordable, and Lee’s engineers had cobbled together a new pontoon bridge at Falling Waters. The Army of Northern Virginia moved out, and by morning all but a division of Hill’s corps had safely crossed to the Virginia side. Kilpatrick’s men sortied to Williamsport, found it empty, and then galloped toward Falling Waters. With the 6th Michigan Cavalry leading the way, the men of Kilpatrick’s command charged Henry Heth’s division of infantry, which was the rear guard of Lee’s army. Buford’s command later joined, but the lack of coordination cost the combined divisions a chance to inflict a heavy blow on the Army of Northern Virginia. Although Brig. Gen. James J. Pettigrew was mortally wounded and hundreds of Confederates were captured, Lee’s army had slipped away. As Buford’s troopers reached the river crossing at Falling Waters, the Confederates on the Southern side cut the ropes holding the pontoon bridge in place, and it swept downriver. The Gettysburg Campaign was over.

The mounted arms of both armies fought long and hard throughout the Campaign. It can be argued that the cavalry of both sides bore the bulk of the Gettysburg Campaign’s burdens, and that the horsemen had been asked to perform superhuman feats. They had done so, to their eternal glory. As Buford put it, “The zeal, bravery, and good behavior of the officers and men on the night of June 30, and during July 1, was commendable in the extreme. A heavy task was before us; we were equal to it, and shall all remember with pride that at Gettysburg we did our country much service.”

Eric J. Wittenberg lives in Central Ohio, where he practices law and writes extensively on the Civil War. He is the author of numerous articles and books, including Gettysburg’s Forgotten Cavalry Actions, winner of the 1998 Robert E. Lee Civil War Roundtable of Central New Jersey Bachelder-Coddington Literary Award.

Help raise the $429,500 to save nearly 210 acres of hallowed ground in Virginia. Any contribution you are able to make will be multiplied by a factor...

Related Battles

866

433

23,049

28,063