Napoleon and the United States

Did he champion or oppress liberty? Did he threaten or aid the interests of the United States? Was he a monstrous dictator or an enlightened despot and culmination of the rise of a common man? Napoleon Bonaparte drew mixed opinions from citizens of the United States. An ocean away from his conquests around the Mediterranean and across Europe, Americans still felt the impact of a changing world. Napoleon influenced American fears, expansion and policies during the first decade and a half of the 19th Century.

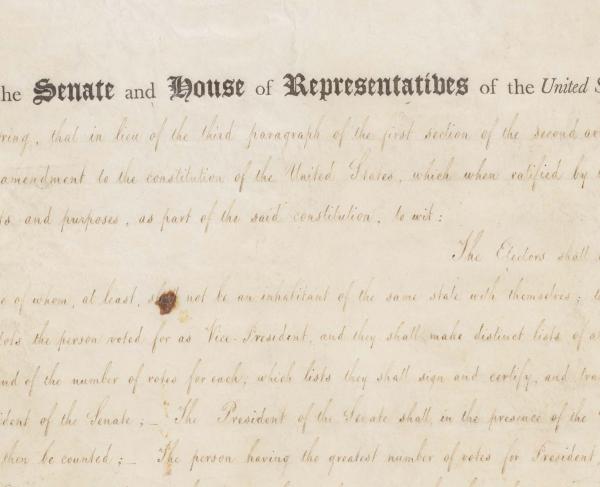

The French Revolution (1789-1799) with its Reign of Terror (1792-1794) challenged and redefined “freedom, equality, and liberty.” While the guillotine bloodied the streets of French cities, the question of freedom reverberated into the French colonies. Toussiant L’Ouverture led an uprising of enslaved people on the island of Haiti (Saint-Domingue) in the Caribbean, killing enslavers and attempting to establish a freer society. While L’Ouverture’s efforts mirrored the deaths of the aristocracy in France and revolutionary quest, the aspect of racial slavery in Haiti made this attempt for freedom and equality a slave insurrection in the perspective of other enslavers in the western hemisphere. Spain, Britain and France became involved in the conflict as alliances shifted and the European powers alternately feared slave insurrection and wanted to steal or protect colonial holdings. The United States initially supported the suppression of L’Ouverture’s revolution, but later shifted perspective, supporting the rebels once their fight became an opposition to Napoleon’s Western Hemisphere ambitions. In Revolutionary France, the National Convention abolished slavery in France and its colonies and reflected this in the French constitutions of 1793 and 1795. However, Napoleon’s rise to power cancelled this provision and prolonged the Haitian conflict.

Napoleon Bonaparte came to power in France in 1799. Thomas Jefferson noted on February 2, 1800, about Napoleon: “Whatever his talents may be for war, we have no proofs that he is skilled in forming governments friendly to the people. Wherever he has meddled we have seen nothing but fragments of the old Roman government stuck into materials with which they can form no cohesion; we see the bigotry of an Italian to the antient [sic] splendour of his country, but nothing which bespeaks a luminous view of the organization of rational government. Perhaps however this may end better than we augur; and it certainly will if his head is equal to true & solid calculations of glory.” The criticism stemmed from the lack of liberty and enlightened governing. To some Americans, Napoleon’s rise to power and eventual self-proclamation as emperor in 1804 represented the death of revolutionary liberty. Napoleon’s dictatorial tendencies made him a more feared adversary when he eyed opportunity in the Caribbean and other parts of North America.

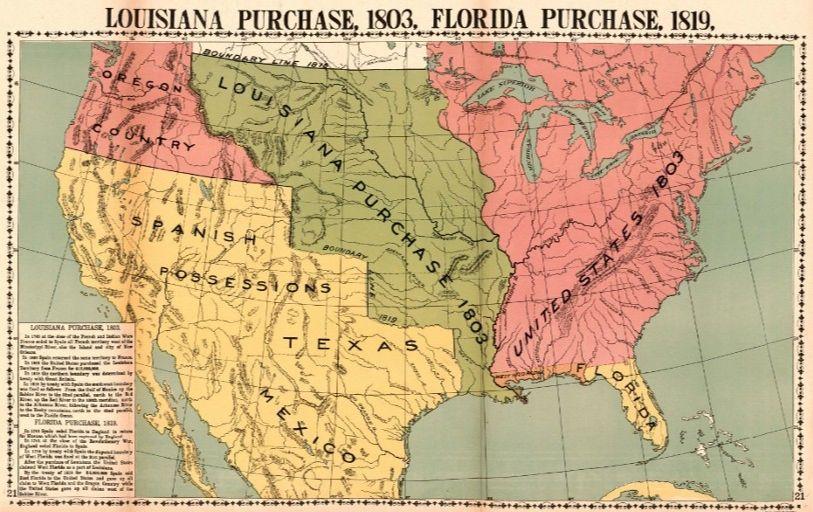

The Treaty of Amiens in 1802 brought a brief period of peace to Europe. Napoleon used the break from campaigns to consolidate power, consider how to fund future wars against other European powers, and evaluate the importance of Trans-Atlantic French territories. France’s colonial holdings in North American included Haiti, the port city of New Orleans, and a large tract of land in the center of the continent called Louisiana Territory. Where these colonial holdings worth defending and could France maintain control if embroiled in an anticipated large-scale European war with Britain?

In 1802, Napoleon sent a military force to Haiti to try to subdue the colonial and regain the profitable agricultural island. The expedition failed, and by 1803, he withdrew French troops from the island. The former enslaved people who had fought for freedom declared Haiti an independent republic in 1804. Popular Haitian tradition claims that Napoleon was going to claim or take the US, but L’Ouverture successful revolution prevented that.

Under President Thomas Jefferson the United States initially supported France’s plan to retake Haiti. However, concerns grew about Napoleon sending troops into the Western Hemisphere, and fears that he would more closely control New Orleans which was a valuable shipping port adjacent to and used by the United States. If Napoleon had goals of empire growth in the Western Hemisphere, New Orleans would be a likely supply center for military expeditions. Some Americans may have believed there was a plot to stepping-stone across the West Indies French holdings, New Orleans, and then to Washington DC, allowing Napoleon to conquer the United States.

By 1800 in a secret treaty Louisiana Territory was returned to France from Spain, though it took Spain several years to hand over the holdings. As early as 1801, Jefferson had sent diplomats to Paris to negotiate to purchase New Orleans. The following year—in response to the French military invasion of Haiti—Jefferson worried about the beginnings a Napoleonic French Colonial Empire and hastily declared neutrality in the Caribbean conflict. Backdoor operations, though, blocked American financial aid to France while allowing supplies to reach the rebels in Haiti. In Paris, diplomats continued pursue a territorial purchase to curb Napoleon’s control of New Orleans and interest in a continental North American empire.

Recognizing that Louisiana Territory would be difficult to defend if Britain tried to seize it in colonial conflict, Napoleon agreed to sell the land to the United States. From Napoleon’s perspective, Louisiana Territory was more useful as cash that he could use to fight new wars in Europe than the possibility of expanding a global empire. To the United States, the 1803 Louisiana Purchase doubled the size of the United States. For $15 million dollars, Jefferson acquired 2,144,480 acres for the United States, and he had secured the port of New Orleans while ensuring that Napoleon would not become a next-door neighbor.

Napoleon crowned himself emperor in 1804 and concentrated on building a huge military force which became the Grand Armee. Numbering approximately 350,000 soldiers, this French army went to war in 1805 against a coalition of European powers—Britain, Sweden, Russia, Austria, Naples, and the Ottoman Empire. For the next seven years, several coalition wars were fought, resulting in Napoleon’s conquest of most of Europe.

While people in the United States breathed a sigh of relief that they were not in Napoleon’s sights, the wars in Europe wrecked the American economy. The United States claimed neutrality and freedom of the seas, anticipating the continuation of maritime trade with Europe. However, the British Royal Navy searched, seized, and prevented American ships from entering French ports, particularly after 1805. Napoleon proclaimed the Berlin Decrees in 1806 which prevented commerce with Britain and showed that he no longer supported freedom of the seas. Thus, the United States was economic embroiled in the conflict indirectly.

The United States Congress responded with the Non-Importation Act of 1806 which banned the importation of some British goods. This was followed with the 1807 Embargo which cut trade with Europe to economically protest; it had minimal effect on Britain and Napoleon’s Europe, but it wrecked the American economy.

Impressment of American sailors in the Royal navy, economic damages, and other maritime grievances eventually led to the War of 1812 between the United States and Britain. America’s war aims were to be settled with Britain, and the conflict was not started to intentionally aid Napoleon. In 1812, Napoleon’s Grand Armee invaded Russia, only to be caught in winter snows. Thomas Jefferson’s attitude toward Napoleon had changed by 1812, and he bitterly called him the “Destroyer of mankind.”

Britain and other coalition armies chipped away at Napoleon’s empire in 1813 and 1814, eventually leading to the emperor’s surrender. Thomas Jefferson gloated to John Adams on July 5, 1814, about Napoleon’s downfall. “The Attila of the age dethroned, the ruthless destroyer of 10 millions of the human race, whose thirst for blood appeared unquenchable, the great oppressor of the rights & liberties of the world, shut up within the circuit of a little island of the Mediterranean, and dwindled to the condition of an humble and degraded pensioner on the bounty of those he has most injured. How miserably, how meanly, has he closed his inflated career!”

With Napoleon shipped off to exile on the Mediterranean island of Elba, Britain sent veteran troops to North America. However, with Napoleon no longer in power, many of the causes of the War of 1812 disappeared, and both sides negotiated for peace and territorial gains. Britain transferred troops back across the Atlantic following the Treaty of Ghent in December 1814 and the Battle of New Orleans in January 1815. Napoleon had one more dramatic military come-back in Europe. In February 1815, he escaped from Elba and took command of the French army again. His brief 100 days venture ended with military defeat at the Battle of Waterloo and final exile to St. Helena Island in the Atlantic Ocean.

Thomas Jefferson wrote judgmentally of Napoleon, summarizing an American view that the emperor had not advanced the cause of liberty or good government. “Bonaparte was a lion in the field only. In civil life a cold-blooded, calculating, unprincipled Usurper, without a virtue, no statesman, knowing nothing of commerce, political economy, or civil government, & supplying ignorance by bold presumption.” From the American perspective, Napoleon had initially appeared as a figure who might be able to bring order to the bloody French Revolution. His need for cash to fund wars helped the United States to acquire the Louisiana Purchase, a significant territorial gain for the country. However, Napoleon’s ambition and empire-building soon made United States’ citizens and official question his motives. Napoleon’s war affected the United States indirectly through the disruption of trade and escalation of conflict with Britain that resulted in the War of 1812.

Further Reading:

Joseph I. Sulim, “Thomas Jefferson Views Napoleon.” The Virginia Magazine of History and Biography 60, no. 2 (1952): 288–304. http://www.jstor.org/stable/4245839.

Bob Corbett, “Napoleon’s West Indian Policy And The Haitian ‘Gift’ to The United States.” Journal of Haitian Studies 2, no. 1 (1996): 71–83. http://www.jstor.org/stable/41715013.