Achieved through a deadly combination of resource superiority and combined arms strategy, the Union’s hard-won gains on the nation’s rivers were instrumental to overall victory in the war.

The geography faced by the western campaigners was quite different from that of their counterparts in the east. Roads were poorer, railroads were fewer, and much of the countryside was untamed. To add to these hazards, the western theater dwarfed the east in terms of square mileage—the west comprised some 385,000 square miles of potential battleground compared to around 95,000 miles in the east.

The importance of rivers in this landscape can hardly be overstated. These swift-running highways afforded the controlling army huge strategic advantages. Soldiers could be swiftly transported to any land point that bordered a controlled waterway. Supply lines were no longer bound to the meager road network. An army that advanced overland with an enemy-controlled river on its flank was in perpetual, crippling danger of surprise attack from the rear.

The rivers were also vital arteries for the Confederate economy, although lines of trade and communication were easily severed by patrolling enemy gunboats. This issue became especially apparent as the Union navy took control of longer and longer swathes of the Mississippi River.

The Civil War began with both sides scrambling to put their navies on a war footing. Although the Federal navy outnumbered its Southern foe, neither side had enough combat-capable warships at the outset of the struggle. The key difference, as in so many other aspects of the war, was Northern development. Once in gear, Northern industry had the capacity to produce a steady flow of vessels, but the Southern shipyards were inferior and vulnerable to attack. To compensate, Confederate resource allocators focused instead on building a formidable series of fortifications along the western rivers.

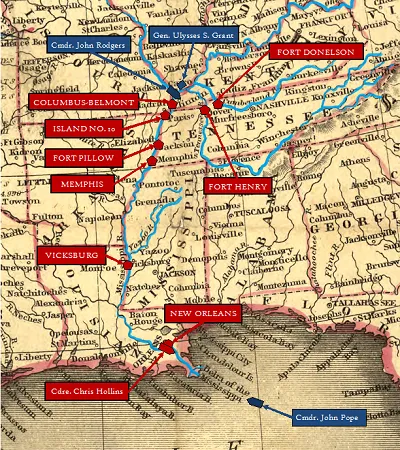

In the summer of 1861, Commander John Rodgers was sent west to lead the Union river flotilla, which at that point contained most of its firepower in three converted paddle-wheel steamers. While awaiting the completion of new ironclad, “City Class” gunboats, Rodgers put his lean force to work. Choosing Cairo, Illinois, at the junction of the Mississippi and Ohio Rivers, as a base of operations, he launched water-borne reconnaissance missions to the north and east, following the borders of Kentucky and Missouri. According to citizen accounts, this projection of power played a substantial role in keeping the two neutral states from throwing in their lot with the Confederacy.

A trio of Confederate forts kept Rodgers and his “Mississippi Squadron” from pushing further south that summer—the wooden gunboats were an impressive sight but could not be expected to go toe-to-toe with Fort Donelson on the Cumberland River, Fort Henry on the Tennessee, or Columbus on the Mississippi. The potential for offensive operations had to wait for the new year, when the City Classers would be ready. In the meantime, the Confederates continued to entrench and reinforce. At the end of August, Rodgers was redeployed to the east in favor of Flag Officer Andrew H. Foote, a stern old salt under instructions to bring coax obstinate infantry commander John Fremont into forward movement.

While liaising with the infantry, Foote formed a relationship with one of Fremont’s subordinates: General Ulysses S. Grant. On November 6, 1861, Foote committed several of his transport ferries as well as two of his three gunboats to supporting Grant’s 3,000-man attack on Belmont, Missouri, just across the river from the fortress at Columbus. Grant won acclaim from the press for the ensuing battle, though he was driven back by Confederate reinforcements, and the Mississippi Squadron won respect from Grant, who escaped capture or death when the transport Belle Memphis turned back and ran out a plank to evacuate him under fire.

This experience was surely a visceral demonstration of the capabilities of combined arms tactics—the military concept of harmonizing disparate weapons and equipment to multiply their effect on the battlefield. At the Battle of Belmont, the movement ability and heavy firepower of the riverboats was used to multiply the ground-taking capability of the infantry. In February of 1862, the Mississippi Squadron now reinforced by the completed City Classers, Foote and Grant were moved to attempt their previous operation on a larger scale.

The target they chose was Fort Henry on the Tennessee River. On February 6, Foote’s transports disembarked Grant and his 15,000 infantrymen five miles away from the fort. They set out overland while Foote’s gunboats—seven in all, four ironclads and the original three timberclads—set out towards the Confederate stronghold.

This time, combined operations broke down. Grant’s men foundered in deep mud and Foote was forced to attack alone. His seven ships moved down the river in two lines, exchanging a severe fire with the fort’s batteries. One ironclad, the USS Essex, took a shell to her boiler and was engulfed in scalding steam—32 were killed or wounded. Nevertheless, Foote pressed his attack home and, after seventy-five minutes of combat, secured the fort’s surrender.

The fall of Fort Henry opened up almost the whole of the Tennessee River to the Mississippi Squadron. Foote immediately sent his timberclads on a raid as far as Muscle Shoals, Alabama, where the shallows prevented further progress. In four days the timberclads captured three warships, seized tons of war material, and forced the destruction of six transport vessels. This sort of action clearly demonstrates the pattern of river warfare—when a bottleneck fort falls, there is little that can be done to protect the rest of the bottle.

Meanwhile, Foote devoted his energy to repairing his ironclads, all in various stages of disrepair following the bruising battle on the Tennessee River. The Essex would be out of action until the summer. Nevertheless, on February 11, only five days after the battle, Grant and Foote pivoted to attack Fort Donelson on the Cumberland.

Marching from Fort Henry, Grant’s infantry had surrounded Fort Donelson by February 14, but several small-scale attacks resulted in nothing but loss for the freezing Union soldiers. On the afternoon of the 14th, Foote moved downriver with seven gunboats, repeating the charging double-line tactic that had subdued Fort Henry. But Fort Donelson was a much stronger position, with its batteries on much higher ground. When the Union vessels closed to within four hundred yards the Confederates let loose, their shot ripping through the weak top armor of the ironclad front line. Each ironclad was hit at least twenty times and Foote himself was wounded, his flagship St. Louis having been holed almost sixty times. By the evening, three of the four ironclads were out of action and Foote ordered a withdrawal.

It was the infantry’s turn to come to the navy’s rescue. In hard fighting on February 15, Grant’s men repulsed a breakout attempt and counterattacked to seize a foothold in the earthworks surrounding the fort. Grant earned the nickname “Unconditional Surrender” the next morning. With the Cumberland open, Nashville, a critical manufacturing and supply hub, fell by the end of February. The outflanked garrison at Columbus quickly withdrew, removing the first obstacle to retaking the Mississippi River.

This opening campaign illustrates the factors through which Union forces eventually achieved dominance of the western rivers. Northern ship production far outstripped the South, a problem exacerbated by David G. Farragut’s capture of New Orleans in April of 1862. This forced the Confederates to rely too heavily on their chain of fortifications. However, the Union's naval strategy for taking a fort was virtually unstoppable: find the best position for each ship to dish out and receive fire, then pound away until the defending garrison reached the limits of its endurance. If the fort was too tough or the ships were too weak, simply wait until stronger guns and thicker armor was provided. Made possible by the fact that ships could move and fortresses could not, this strategy produced inevitable success.

One by one, each fortress-cork was popped by the pressure of combined land and riverine assault. The South’s lack of waterborne firepower precluded effective counterattacks. Once taken, there was no swath of any western river that the South managed to regain.

The fall of Vicksburg in the summer of 1863 brought the Mississippi entirely under Union control and split the Confederacy in half. Union forces used their increasing control of the waterways to concentrate more and more strength at decisive points while Southern armies could barely risk an advance with exposed waterways in their rear.

Ultimately, the South’s static defense on the rivers could not contend with the irresistible mobile offense executed with such skill by officers such as Foote, Grant, and Farragut. In a military and economic sense, the loss of the inland arteries all but dismembered the Confederacy.

Help the Trust save 161 acres across consequential Western Theater battles — Fort Heiman and Fort Henry, Brown’s Ferry/Chattanooga, Spring Hill, and...

Related Battles

607

641

42

21

2,691

13,846

4,910

32,363