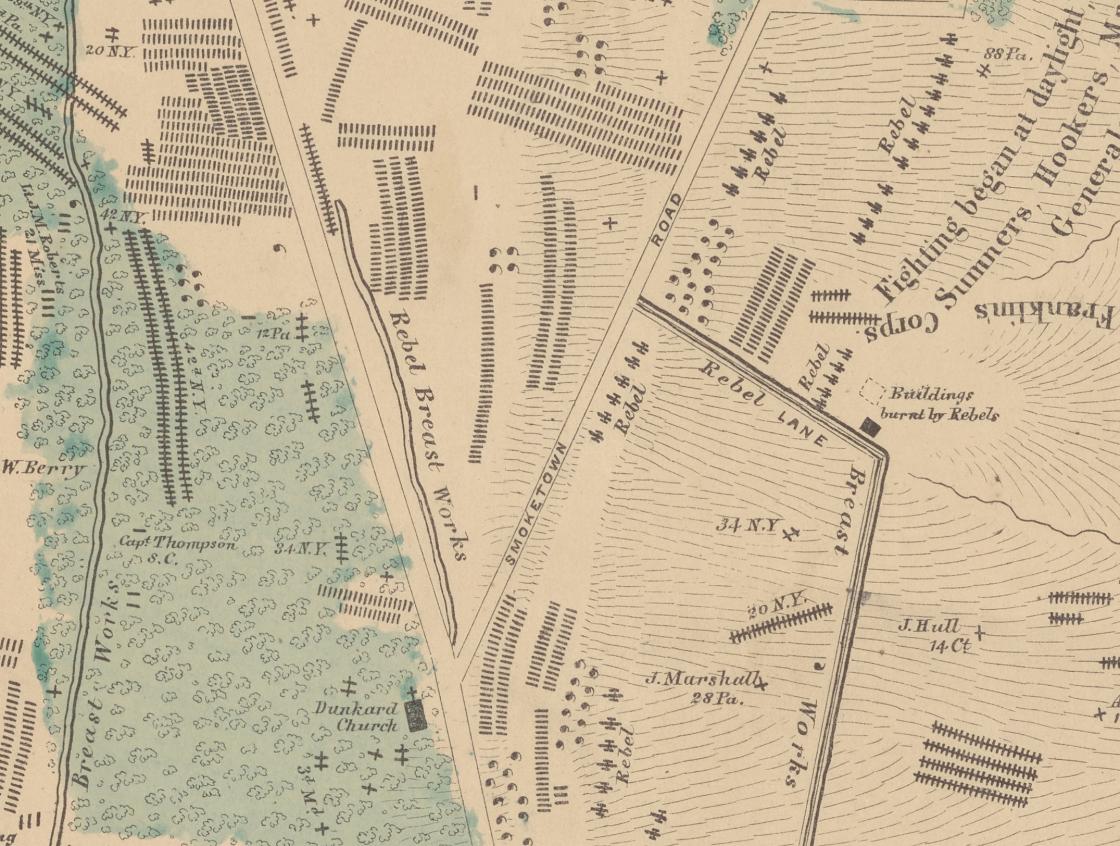

The gruesome task of exhuming and reinterring thousands of bodies on the Gettysburg Battlefield was made easier by early efforts to locate and document the temporary burial places of countless soldiers. To modern historians, the most widely known of these efforts is the survey published in 1864 under the name “S. G. Elliott.” This map — considered without parallel until a “sister” document showing the Antietam Battlefield emerged in 2020 — which delineates 8,352 individual burial locations and 345 dead horses, was for many years out of circulation, ultimately reappearing in the collections of the Library of Congress during the 1930s. According to Civil War historian William A. Frassanito, the Elliott map represents the first professional post-battle survey of the field. And while it has been used in hundreds, if not thousands, of books, articles, and Gettysburg studies, very little has been written about its origin or its mysterious creator.

Finding S.G. Elliott

Until the summer of 2020, no published work delved into the identity of S.G. Elliott in conjunction with Gettysburg, and it was research into this question that allowed the Antietam Burial Map to come into the public consciousness. This may be attributed to the absence of period references, particularly in local newspapers, to Elliott’s presence in Gettysburg during the map’s creation. This is odd, given that the map appears to have been commissioned by Gettysburg’s own David Wills and other representatives of the newly established Soldiers’ National Cemetery Commission in 1864. Adding confusion to the story is the fact that Elliott could not have been in Gettysburg until, at the earliest, late January of 1864, when a majority of Union dead had already been moved to the new cemetery. Thus, the map reflects a landscape that no longer existed for Elliott when he reached Gettysburg. Because of this, it is evident that Elliott’s map does not reflect his own fieldwork, but is instead based on an earlier survey, or surveys, conducted by associates of Wills.

The identity of S.G. Elliott as California railroad engineer Simon Green Elliott is based on two sources. The first is an August 1, 1864, Philadelphia Press article, which states that “a good, we might say the only reliable, map of ‘The Battlefield of Gettysburg’ is that made by S.G. Elliott, of California, who, while visiting this State, was induced, by many personal friends, to make an accurate survey of the ground by transit and chain.”

The second source is an article in Marysville, California’s, Daily Appeal of July 20, 1864:

S. G. Elliott, Chief Engineer of the California and Oregon Railroad...visited the battlefield of Gettysburg, as a matter of curiosity, and it occurred to him that an accurate map of that historical ground would be a source of public interest, and following up this idea, made a survey and map which he has just had engraved in Philadelphia. This map shows the location of the Union and rebel breastworks, where the batteries were placed, and also locates all the graves of the killed in that fearful encounter. This latter feature is something new in map making, and it shows the intensity and deadliness of the struggle at the various points as the killed of both sides were buried on the spot where they fell. On examination, the map becomes an absorbing interest, and it is invaluable as a record of those three days’ battles…. The map will soon be for sale in California.

Who was Simon G. Elliott?

Simon Green Elliott was born March 27, 1828, in Pittsfield, New Hampshire. One of at least nine children, he was the son of Joseph Elliott, a farmer, and Betsey Seavey. In 1855, at the age of 27, he made the long journey to California, where he would reside permanently for roughly the next decade. Inspired by the 1849 gold rush and “in search of a fortune,” he settled in Beal’s Bar, a prominent gold mining camp near the American River.

In 1856, Elliott began his public career as a surveyor, although, according to journalist Henry Villard, he had “nothing but an ordinary school education.” But Elliott’s skills were enough to warrant his appointment as road supervisor. The following year, Elliott ran for and won the position of Placer County surveyor. Three years later, he was hired to survey the boundaries between Sutter, Sacramento and Placer Counties. The following year, he conducted a much larger survey for executives of the Sacramento, Placer and Nevada Railroad Company. Elliott was to find a suitable rail route between Northern California and Nevada. After completing his travels, he had a map engraved and published, with his name prominently displayed in bold cursive script.

.

During the summer of 1863, Elliott was elected chief engineer of the Oregon and California Railroad Company. He was tasked with surveying a rail route between Marysville, Calif., and Portland, Ore., a 641-mile stretch. However, several months into the expedition, Elliott and his companions became embroiled in a dispute and, at the same time, ran out of funds to support their work. Desperate and frustrated, Elliott “left the party in possession of all its equipment and returned south to California” without completing the survey. On November 20, 1863, one day after President Abraham Lincoln’s Gettysburg Address, Elliott falsely reported to local papers that “the party…completed its work,” and that he was prepared to travel to Washington to lay “the claims and merits of the enterprise before Congress, [solicit] grants of land, right of way, and such other aid as Congress may see fit to bestow.” And so, with a multimillion-dollar project hanging in the balance, Elliott began his voyage east, arriving in New York City by boat on January 18, 1864.

The Elliott Maps

While in Washington lobbying on behalf of the proposed Oregon and California Railroad, Elliott produced at least two detailed surveys of the Gettysburg and Antietam battlefields. How exactly he became connected with officials at either site is not known, but it does appear that he was given access to original, detailed surveys of temporary burials on both fields. By January 1864, a majority of Gettysburg’s Union dead had been removed to the new Soldiers’ National Cemetery. But Elliott’s map shows these very same bodies on the field where they fell. Furthermore, Elliott’s maps show dead horses on both battlefields that would have been either burned or buried long before his arrival in Washington. This evidence suggests that Elliott’s maps were not original, perhaps copies of earlier work created by community members like David Wills at Gettysburg and a team of local surveyors at Antietam. In the case of Wills, Pennsylvania newspapers actually reported that he had commissioned a detailed survey of temporary burial locations within two weeks of the battle — quite an impressive feat.

However, several important questions remain unanswered about the timing, purpose and contents of the Gettysburg Elliott Map. For instance, its commercial value remains uncertain. Perhaps David Wills sought to impress upon the public the monumental task his team had accomplished in moving thousands of bodies from improper graves to the new Soldiers’ National Cemetery. Or, perhaps Elliott sought to capitalize on the national interest Gettysburg was receiving and convinced Wills to engage his services. If Wills sought lasting financial support for the cemetery, he may have seen Elliott as a vehicle to spread the news about Gettysburg’s new cemetery — a win-win. Regardless, it is clear that the map was not intended to be used as a tool to locate individual graves on the battlefield. In fact, out of more than 8,000 graves notated, Elliott identified just 17 by name.

Elliott’s map of Antietam, also created in 1864, was recently digitized by the New York Public Library and discovered by historians at the Adams County Historical Society during the research for this article. This survey bears striking resemblance to his Gettysburg work, with the same key features employed. One major difference is the fact that far more individual burials are identified by name on the Antietam map. Because Antietam’s dead were not relocated to a cemetery until after Elliott’s work in 1864, perhaps he had greater access to field notes from earlier surveys.

Regardless of the specific circumstances of Elliott’s work on these surveys, it is now apparent that he was nowhere near either Gettysburg or Antietam when the initial burial information was being collected. His maps were undoubtedly based on the efforts of earlier surveyors, and, in the case of Gettysburg, may represent the field as it appeared within mere days of the battle. Elliott deserves credit for compiling this valuable information and having it published. It may well be the closest historians come to understanding the physical aftermath of America’s costliest battles.