Shaping a Volunteer Army

Hallowed Ground, Spring 2011

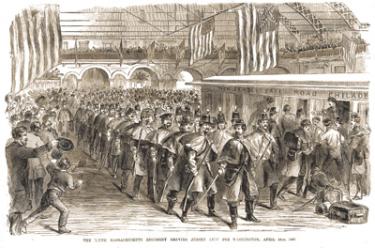

At the outbreak of the Civil War, the U.S. Army consisted of just 16,000 men — fewer than 200 companies, nearly all of which were stationed west of the Mississippi River. Although made up of trained career soldiers, a force of this size was insufficient for the scale of conflict the Civil War promised to be. Understanding this, upon the bombardment of Fort Sumter by Confederate forces, President Abraham Lincoln called for 75,000 volunteers to quell the insurrection.

Accommodating such a surge in the ranks would be additionally complicated by the fact that much of the officer corps were Southerners by birth and chose to resign their commissions and throw their lots in with the Confederacy. Of the roughly 820 West Point graduates on active duty at the outbreak of the war, 184 enlisted in Confederate service. Former officers then living as civilians also returned to military service at the outbreak of the war, with 99 of them heading to Richmond.

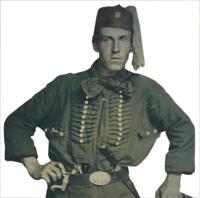

To fill out the command structure, both sides relied on appointments, often made by state governments to complete their burgeoning regiments of volunteers. Often termed political officers, since they were typically installed by the governor, these men came from a wide variety of backgrounds and, accordingly, were widely divergent in their abilities and successes.

All new soldiers, officers and enlisted men alike, had to learn the basics of military training. Former businessmen, politicians, doctors and lawyers spent their evenings pouring over field manuals and treatises on tactics and other martial matters. Their days were spent on the parade grounds, learning to drill along with their men. For recruits of all ranks and stripes, camp life could be dull; the reality of learning to march and form lines of battle did not match the romanticized imaginings of war they had harbored. Veteran officers insisted these skills, though tedious, could be the difference between life and death on the battlefield, but the green troops found this difficult to believe.

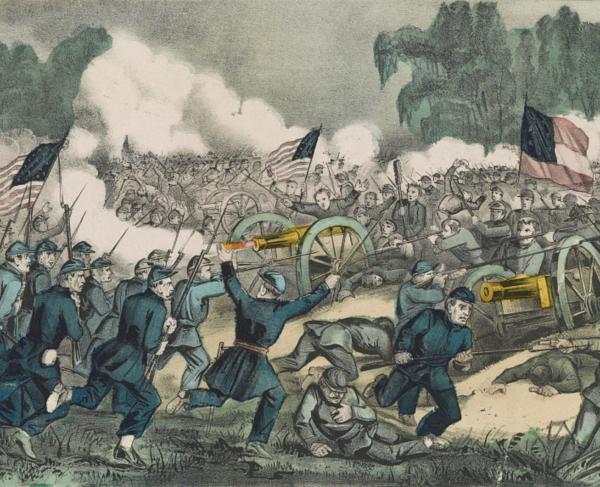

The grim realities of war came home to roost following the First Battle of Manassas. Having now “seen the elephant,” the new soldiers understood that by making the tasks of marching, deploying and firing second nature, they were able to function as a unit. The heat of combat also exposed several other major obstacles for the new fighting forces to overcome.

At this early stage of the war, uniforms for the two sides had not been standardized. Raised by their individual states, many regiments wore uniforms reminiscent of their state militias, creating a veritable rainbow on the battlefield as various units — on both sides — sported elements of navy, royal and sky blue; gray; green; red and gold. In several instances, the friendly fire incidents that resulted from the ensuing confusion had decisive results. In response, the Confederacy put formal dress regulations into effect in September 1861, stating that trousers, jackets, caps and greatcoats should all be gray.