By Bob Allen

Henry Clay Ford was counting receipts in the box office of Ford’s Theatre, which his older brother John owned, on the night of April 14, 1865. Around 10:00 p.m., he heard a faint, percussive pop.

At first, Ford assumed someone had accidentally fired a blank stage prop pistol in the property room. But when he glanced up, Ford was surprised to see his good friend John Booth on stage. Although Booth was a familiar and welcome presence around Ford’s Theatre — a popular member of its extended “family” of actors and stagehands — he definitely wasn’t in the cast of that evening’s performance of Our American Cousin. In fact, the last time he had taken the stage had been almost a month prior, playing the villainous lead in a benefit performance of a melodrama called The Apostate to raise money for a fellow actor’s draft exemption.

In the blink of an eye, Booth was gone, and the audience was silent. Before the crowd could grasp the immensity of Booth’s actions, he’d made his way out the back door, mounted his horse, and fled down F Street toward the Navy Yard Bridge. W.J. Ferguson, a young bit actor in the theater that Good Friday evening, later said, “So completely hidden had been the tragedy that hundreds in the house had not the least idea of the profound seriousness.”

But as the acrid smell of gun smoke spread, and Mary Lincoln’s aggrieved shrieks pierced the silence, grim reality began to set in. Within hours, the president of the United States lay dead from an assassin’s bullet, and the largest manhunt in American history was underway.

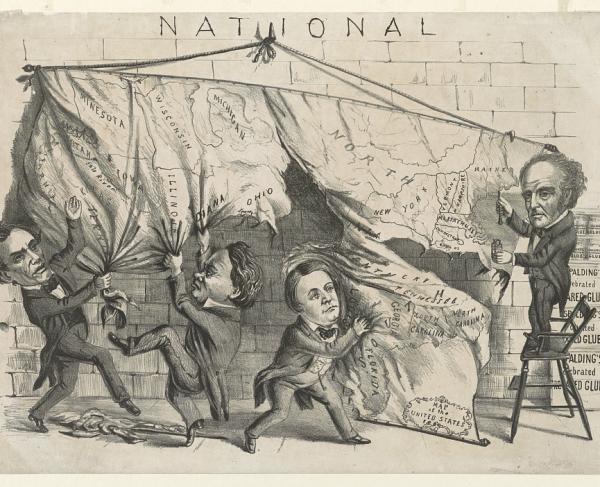

Persistently revisited and rehashed over the ensuing decades, the events and characters associated with the Lincoln assassination have become one of the most dramatic and symbolic chapters in our national historical narrative. According to data published by the Surratt Society, by 1997, more than 3,000 books, monographs and articles had been published on the assassination and subsequent military trial of the conspirators. And this number continues to grow.

In later years, former friends recalled that, as a boy, Booth dreamed of having his name writ large in history. If so, he succeeded. Nearly every schoolchild knows of his deeds; the image of the mustachioed assassin leaping over the theater box balustrade onto the stage is frozen in time and seared in our collective memory.

In Search of John Wilkes Booth

“Say what we will to the contrary, and be as indignant at the imputation as we please, Booth was the product of the North, as well as of the South. He was moulded as well by Northern as by Southern pulpits, presses, and usages.”

Abolitionist Gerrit Smith speaking at a Cooper Institute meeting in New York, June 1865

Who exactly was this man who shot the president? John Wilkes, second youngest of the 10 children of acclaimed English-American actor Junius Brutus Booth, Sr., was born in Harford County, Maryland, just a stone’s throw south of the Mason-Dixon Line. He came from a politically divided family and a politically divided region. In letters written during the war, Booth’s mother Mary Ann referred to Confederates as “the enemy.” His older brother, Edwin, a nationally acclaimed actor by the early 1860s, voted for Lincoln in 1864.

Years earlier, John Wilkes’s grandfather, Richard Booth, had retired as a London barrister and joined his son and grandchildren in America, where he aided runaway slaves on the Underground Railroad. John Wilkes’s father, Junius, was a self-styled vegetarian and pacifist, but that didn’t stop him from penning a death threat to his friend, President Andrew Jackson, in 1835.

As a teenager, the future assassin resolved to follow in his father’s footsteps and began his career as a bit player in the theaters of Philadelphia, appearing under the stage name “J. Wilkes.” It was in Richmond, Va., during the 1859–1860 season, that he rose to regional stardom as a member of a theater company managed by John T. Ford, a childhood friend who would soon open Ford’s Theatre in Washington, D.C.

In December 1859, Booth witnessed the execution of the militant abolitionist John Brown, which had a profound effect on him. Though Booth hated everything the abolitionist stood for, he later spoke admirably of his courage in staking his life on his convictions and stoically accepting the consequences of his actions.

In late 1860, still in his early 20s and on the cusp of national stardom, Booth embarked on his first tour of northern cities as a leading man. His theatrical success continued despite the war; during the 1863–64 theatrical season, Booth earned $20,000 (a significant sum, given Lincoln’s presidential salary of $25,000). But in letters to his mother, Booth poured out his anguish and remorse over living the good life among his “enemies,” while Southern patriots fought and died in the field.

Despite his mixed emotions and growing fanaticism, Booth was certainly well liked by his peers. Years after the assassination, Clara Morris, a friend and fellow actor, said:

“At this late date the country can afford to deal justly with John Wilkes Booth…. He was not a bravo, a commonplace desperado, as some would make him…. It was impossible to see him and not admire him; it was equally impossible to know him and not to love him.”

E.A. Emerson, another contemporary, remembered Booth as “a kind-hearted, genial person…. Everybody loved him on stage, though he was a little excitable and eccentric.”

Cleveland theater manager John Ellsler, who had partnered with Booth as a prospector in the West Pennsylvania oil fields in 1864, praised him as “as manly a man as God ever made.” Through his older brother Edwin, John Wilkes even became acquainted and got on well with the abolitionist Julia Ward Howe. He was a charmer and a chameleon, capable of being all things to all people.

He was also a man of contradictions. In July 1863, Booth was visiting his brother Edwin in New York City when the Draft Riots broke out and impoverished Irish protesters, enraged by the provision in the conscription law that allowed one to buy out of military service, vented their anger on black residents of the city, who they saw as competitors for jobs. Booth took it upon himself to personally protect Edwin’s black servant from harm amid the lethal violence. Adam Badeau, a close friend of Edwin’s who would later serve as a Federal colonel on Lt. Gen. Ulysses Grant’s staff, was also a houseguest at the time and later claimed he had no idea his best friend’s younger brother harbored such rabid pro-Southern, pro-slavery sentiments.

“You are in danger”: Lincoln was no stranger to assassination threats

“I regret that you do not appreciate what I have repeatedly said to you in regard to proper police arrangements connected with your household and your own personal safety. You know, or ought to know, that your life is sought after, and will be taken unless you and your friends are cautious; for you have many enemies within our lines.”

Letter written to Lincoln by his friend and occasional bodyguard Ward Lamon, December 1864

Lincoln was no stranger to mortal danger; he even kept a file in his desk labeled “assassination,” in which he presumably collected the most colorful or credible missives from those eager to take his life. The threats against the 16th president began shortly after he left Illinois in February 1861 on his long, circuitous journey to his first inauguration and continued more or less unabated throughout the rest of his life. New York newspaper editor Horace Greeley reasoned that if he received more than 100 death threats during the war, Lincoln must have gotten more than a thousand.

A fair share of this vitriol emanated from north of the Mason-Dixon Line. A Wisconsin newspaper editor named Marcus Mills Pomeroy repeatedly excoriated Lincoln in his La Crosse Democrat, opining that if Lincoln should be re-elected “to misgovern for another four years, we trust some bold hand will pierce his heart with a dagger point for the public good.”

Surprisingly, despite this treacherous undercurrent, presidential security was, at least early in the war, practically nonexistent. Lincoln was frequently spotted riding or walking alone in and around Washington, D.C. He often took solitary, late-night walks to the nearby War Department telegraph office to peruse the latest dispatches from the front, even though the White House grounds were open to the public.

One evening in 1864, when the president rode alone on horseback from the White House to his Summer Cottage at the Soldiers Home (then well beyond the ambits of the city), someone took a shot at him from fairly close range.

The Roots of Conspiracy

“It seems that uncontrollable fate, moving me for its own ends, takes me from you, dear Mother, to do what work I can for a poor, oppressed, downtrodden people … I have not a single selfish motive to spur me on to this, nothing save the sacred duty, I feel I owe the cause I love, the cause of the South. The cause of liberty and justice.”

Letter from J. Wilkes Booth to his mother, Mary Ann Booth, November 1864

As early as mid-1863, the character of the war began to take an insidious turn. Long gone were the chivalric days of 1861 and 1862 when Union Maj. Gen. George McClellan assured Southerners he would not destroy their property. By 1864, covert, “black flag” operations were sanctioned by both sides.

In early March 1864 came the infamous and unsuccessful Dahlgren-Kilpatrick Union cavalry raid, a failed attempt to free Union prisoners of war housed in Richmond, Va. After Confederate pickets killed one of the retreating commanders, Col. Ulric Dahlgren, a letter was found on his corpse. It appeared to be a speech he’d intended to give to his troops. In it he resolved to: “destroy and burn the hateful city,” adding for good measure, “Jeff Davis and cabinet must be killed on the spot.”

Dahlgren’s incendiary letter was widely reprinted in newspapers on both sides of the conflict, fanning the hatred of fanatics like Booth. Precisely where and when John Wilkes Booth decided to immerse himself in criminal intrigue against Lincoln is unclear, but after spending much of the summer of 1864 as an investor and prospector in the Pennsylvania oil fields, he journeyed to Baltimore in September and met with the first two men to enter his conspiracy: his childhood friends Sam Arnold and Michael O’Laughlen.

From then until sometime in the early spring of 1865, Booth sought to abduct President Lincoln so that the Confederate government could use him as a bargaining chip in negotiations for a conditional peace and the exchange of Southern soldiers in Union prison camps. As he laid out various scenarios for accomplishing the deed, Booth made several trips in late 1864 to southern Maryland, which, although under nominal Federal occupation, was a hotbed of covert Rebel activity. At this point, Booth planned to include a physician in his abduction party — as a gesture of good faith that Lincoln would be delivered to Richmond without harm befalling him — and, presumably, this is where Dr. Samuel Mudd, Jr., entered the picture.

But after months of delay and fruitless intrigues, Booth made only one feckless effort to nab Lincoln on March 17. It came to naught when the president had a last-minute change of schedule and ended up not taking the road to the Soldiers Home, where the would-be kidnappers lay in wait for him.

Meanwhile, events were moving fast and soon rendered the kidnapping scheme irrelevant. On April 3, 1865, Union troops occupied Richmond, Va., and, within a week, Gen. Robert E. Lee had surrendered the Army of Northern Virginia. In their hearts and minds, most Southerners, as well Northerners, realized the writing was on the wall. There was, however, a small but committed minority who believed the tide could still be turned. If Booth could create an interval of chaos, such as in the wake of an assassination, to paralyze the highest echelons of the federal power structure, these die-hard Confederates could rise from the ashes and renew the struggle. Justification for this rationale came from the fact that not all Confederate generals had surrendered their commands — scattered fighting continued in the Western Theater until the Battle of Palmito Ranch, Texas, in May. Moreover, Jefferson Davis and other Confederate officials remained at large after fleeing the capital.

On the Brink

The conspirators made their preparations against the backdrop of a capital city in giddy celebration, all military bands, firework displays and grand illuminations. Government offices shut down and sent their workers packing, even as taverns swung their doors wide open to receive them.

Booth, meanwhile, was short on manpower to execute his plans: three conspirators — John Surratt, Jr., Samuel Arnold and Michael O’Laughlin — had lost faith in him. Wanting nothing to do with killing, they abandoned the conspiracy. With them gone, it was down to Booth and three bitter-ender accomplices: Lewis Powell (a.k.a., Lewis Paine), a former Confederate soldier who was wounded the second day at Gettysburg and later rode with Mosby’s Rangers; George Atzerodt, a Prussian-born, alcoholic carriage painter and free-booting blockade runner for the Confederacy; and David Herold, the 22-year-old son of a former Federal Navy Yard official.

Around mid-day on Good Friday, Booth made his customary visit to Ford’s, his home away from home in Washington, to get his mail. When Henry Ford informed him that Lincoln was planning to attend the theater that evening, Booth showed no outward reaction, but he must have rejoiced internally.

His opportunity now apparent, Booth stopped by the Surratt Boarding House to tend to some final details. Later in the afternoon, he was seen in Baptist Alley astride his rented horse, apparently going through the paces for a fast getaway, much like a sprinter practicing coming out of the starting blocks.

Around 8:00 p.m., Booth held a final meeting with his ragged band of co-conspirators — Powell, Atzerodt and Herold — at the Herndon House hotel. There, just a block away from Ford’s, he assigned their final, bloody tasks.

With a Single Shot

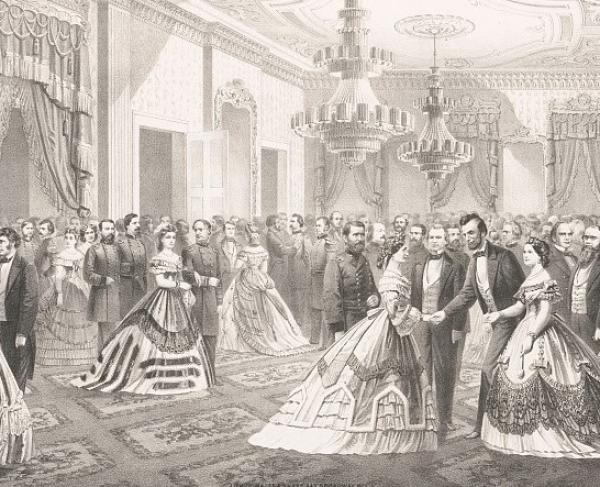

Our American Cousin was already in progress when President and Mrs. Lincoln, along with their two guests —Maj. Henry Rathbone and his fiancée and stepsister Clara Harris — and a small entourage, arrived at Ford’s to considerable fanfare.

John Parker, a Washington policeman assigned to the White House, accompanied the presidential party, as did Lincoln’s footman Charles Forbes. Once the Lincolns were settled in the state box, the stage action resumed, and Forbes and Parker left, presumably to get a drink next door at the Starr Saloon. Forbes soon returned and took a seat just outside the state box, but Parker’s whereabouts at the time of the shooting are unknown.

It was, in fact, not unusual for Lincoln to attend Ford’s without anyone guarding, or even monitoring, traffic in and out of the state box. That was the case one evening in February 1865 when Lincoln attended Ford’s with Lt. Gen. U.S. Grant and Maj. Gen. Ambrose Burnside as his guests.

Booth returned to the theater around 9:00 p.m. by way of Baptist Alley and entered through a rear door. After chatting briefly with the doorman out front, Booth adjourned to the adjacent Star Saloon for a drink.

Shortly after 10:00 p.m., Booth re-entered Ford’s and proceeded up the staircase to the dress circle, calmly humming a tune. He strode resolutely down an outer aisle and presented a card of some kind (it never has been determined exactly what) to Charles Forbes, who let him pass.

Booth entered the narrow passage onto which the doors to the state box opened. He closed the door behind him and wedged it shut with a board he had earlier cut from a music stand. Booth had acted in Our American Cousin many times and was thoroughly familiar with its comedic ebbs and flows. He waited for a particular scene, when only one person would be on the stage and the dialogue usually provoked loud peals of laughter from the audience.

When the moment came, he opened the inner door to the president’s box and shot Lincoln point blank in the back of the head with his derringer (some witnesses claimed that he shouted “Freedom!” during or immediately following the act). Rathbone grappled with Booth, managing to grab hold of a button on his coat before being slashed on the upper left arm by the assassin’s dagger. The scuffle was enough to throw Booth slightly off balance, and as he made the 12-foot leap to the stage, he caught one spur in the treasury flag decorating the railing. He landed in an awkward crouching position and broke the fibula in his lower left leg. According to various eyewitness accounts, he shouted either “Sic Semper Tyrannis” (the state motto of Virginia, “Thus always to tyrants”) or “The South is avenged!” as he rushed off the stage and out the rear exit. Once in Baptist Alley, Booth mounted his horse and galloped down F Street, toward the Navy Yard Bridge (near today’s 11th Street Bridge).

On the Run, out of the Capitol

Meanwhile, Lewis Powell was sent to kill Secretary of State William Seward. At the time, Seward was bed-ridden at his residence on Lafayette Square, recovering from a serious carriage accident nine days earlier.

Posing as a druggist’s delivery clerk, Powell tried to bluff his way into the house, and when that failed, he bludgeoned and slashed his way into Seward’s bedroom, where Lincoln had visited the secretary four days earlier. Powell stabbed Seward repeatedly with his dagger and injured several others in the household who tried to stop him. Miraculously, they all survived.

Herold, unlike Powell, was not a killer, and Booth probably realized it. But he knew his way around Washington and accompanied Powell, a country boy with no sense of direction in the big city. As Powell carried out his violent assignment upon the Seward household, Herold, still astride his horse outside, was unnerved by the bloody shrieks and galloped off.

Herold was riding a horse he’d rented from Nailor’s Stable. John Fletcher, the man who had rented Herold the steed, did not trust him. As the hour grew late, Fletcher began to worry that Herold meant to steal the horse and went looking for him. He encountered Herold on Pennsylvania Avenue and demanded his horse back. Not about to give up his mount at this juncture, Herold galloped off toward the Navy Yard Bridge with Fletcher in pursuit. Although the bridge was guarded by Sgt. Silas T. Cobb, restrictions on crossing had been relaxed after major hostilities ceased in the Eastern Theater; both Booth and Herold were allowed across following only a brief interrogation.

Fletcher reported the theft’s details to the police, and authorities began connecting the dots: a growing series of reports indicated Booth was headed for southern Maryland.

Familiar Stops for the Fugitives

After rendezvousing at Soper’s Hill (the exact location has never been determined, but presumably in the vicinity of present-day Temple Hills, Md.), Booth and Herold stopped next at the Surratt Tavern in Surrattsville (now Clinton), Md., about a dozen miles from Washington.

The tavern, like a downtown boardinghouse where several conspirators occasionally stayed, was owned by Mary Surratt. Her husband had died in 1862, leaving her with considerable property but also significant debts. During the war, both the house and the tavern in Prince George’s County (where Lincoln got exactly one vote during the 1860 presidential election) were designated safe houses on the “secret line” that the Confederacy established for covertly moving everything from mail and newspapers to escaped prisoners and spies between Richmond and Washington. In the fall of 1864, however, Surratt rented the tavern to a man named John Lloyd and moved to the house on H Street, where she took in boarders to make ends meet.

When Booth and Herold arrived at the tavern around midnight on April 15, they did not linger long. Booth stayed on his horse while Herold pounded on the door and roused Lloyd, who was well into his cups. Herold grabbed a bottle of whiskey and sent Lloyd upstairs to get “those things,” which turned out to be two carbines and a field glass.

These items were part of a cache of weapons, ammunition and other paraphernalia that had been hidden by Mary’s youngest son, John Surratt, Jr., the Confederate courier and agent who had previously colluded with Booth, but had subsequently attempted to leave the conspiracy. The items had been stashed the day after Booth’s aborted March 17 attempt to kidnap Lincoln on the lonely road that led to the president’s cottage at the Soldiers Home. The field glass belonged to Booth and had been taken to the tavern by Mary Surratt at Booth’s request on the afternoon of April 14. As Booth and Herold were leaving, Booth nonchalantly informed Lloyd, “I am pretty certain we have assassinated the President and Secretary Seward.”

Around 4:00 a.m., Booth and Herold arrived at the home of Dr. Samuel A. Mudd in Charles County. Whether the visit to Mudd’s was planned or merely a last-minute detour to get Booth’s broken leg set is unknown, but the pair were clearly acquainted; Booth had visited Mudd’s house at least twice in late 1864. On one of these trips he bought a “one-eyed” horse (blind in one eye) from Mudd’s neighbor George Gardiner — a mount later ridden by Lewis Powell the night of the assassination. In December, Mudd had introduced Booth to John Surratt, Jr., and the trio met at the National Hotel in Washington.

Years later, it was revealed that, in December 1864, Mudd also introduced Booth to Thomas Harbin, a ranking Confederate agent operating in southern Maryland. After hearing the outline of the plan to abduct Lincoln, Harbin assured Booth that, could he pull it off, the Confederate underground would provide aid and support to bring the president across the Potomac to Richmond.

Into the Wilderness

“I am here in despair. And why? For doing what Brutus was honored for — what made [William] Tell a hero. And yet I, for striking down a greater tyrant than they ever knew, am looked upon as a common cut-throat …. (I) am sure there is no pardon in the Heaven for me, since man condemns me so.”

Entry in John Wilkes Booth’s so-called diary, written while in hiding a pine thicket in southern Maryland

It was around 5:00 p.m., on Saturday, April 15, when Booth and Herold left Mudd’s house and rode off into nearby Zekiah Swamp, where they promptly got lost. With a free black man named Oswell Swann serving as their guide, they arrived around midnight at Rich Hill, the home of Samuel Cox, an influential Charles County landowner and ardent Confederate. Cox fed the fugitives, then, in the pre-dawn hours, had his farm manager, Franklin Robey, conceal them in a pine thicket near Bel Alton. The thicket was, conveniently, not on Cox’s property.

Shortly after sunrise on Sunday, Cox summoned his foster brother, Thomas Jones, a farmer and fisherman. Jones had long been active in the Confederate underground and had spent time in Washington’s Old Capital Prison as a result of his activities. Cox knew that Jones was deeply familiar with the tides and currents of the wide Potomac River, and that his boats had survived the Federal seizures designed to minimize Booth’s chances of escaping across the river. Just as important, Cox knew that Jones, though he’d been impoverished by the war, could be trusted and would keep a secret.

For five days, Jones took food and drink, as well as newspapers, to the pine thicket as he waited for an opportunity to move Booth and Herold across to Virginia. This was no easy task, since the Potomac was now under constant surveillance by Federal gunboats and shore patrols.

Jones left the only descriptions we have of Booth’s exile in the pine thicket and of the subsequent river crossing. He wrote these observations, along with his first impressions of Booth, in an 1893 monograph called J. Wilkes Booth.

“He was lying on the ground with his head supported on his hand. His carbine, pistols and knife were close beside him. A blanket was drawn partly over him. His slouch hat and crutch were lying by him … though he was exceedingly pale and his features bore the evident traces of suffering, I have seldom, if ever, seen a more strikingly handsome man …. His voice was pleasant; and though he seemed to be suffering intense pain from his broken leg, his manner was courteous and polite.”

Jones conceded that, given the risks, he’d entered this task with great reluctance, but, “no sooner had I seen him in his helpless and suffering condition than I gave my whole mind to the problem of how to get him across the river.”

The Other Conspirators’ Fates

“If this conspiracy was thus entered into by the accused … then it is the law that all the parties to that conspiracy, whether present at the time of its execution or not, whether on trial before this Court or not, are like guilty of the several sets done by each in the execution of the common design. What these conspirators did in the execution of this conspiracy by the hand of one of their co-conspirators they did themselves….”

Summation of the Hon. John Bingham, Special Judge Advocate in the Lincoln Assassination Conspiracy Trial

While hiding in the thicket, Booth pored over the papers that Jones brought him and finally learned how his co-conspirators had fared and how the world was reacting to his deed. Needless to say, he was not encouraged. In his diary, he even expressed “horror” at all the needless carnage in the Seward household.

Neither Powell nor Atzerodt, it turned out, had succeeded at their bloody endeavors. After fleeing from Lafayette Square, Powell got lost and never made it to the Navy Yard Bridge. He abandoned the one-eyed horse and most likely hid out in the Old Congressional Cemetery. By Monday night, April 17, he was cold and hungry and returned to the only place he knew to go: the Surratt boardinghouse. He had the misfortune of arriving just as five military detectives had returned to the house to resume interrogations of Mary Surratt and her boarders. Powell was arrested on the spot.

On April 14, Booth had ordered Atzerodt to find Vice President Andrew Johnson at a hotel named the Kirkwood House and shoot him. Atzerodt objected strenuously, telling Booth he had only intended to kidnap, not kill, and wandered off to have a few drinks. He then proceeded to the Kirkwood House, where he lingered over a few more drinks and asked after Johnson. Eventually, he stumbled back out on to the street, where he tossed the dagger Booth had given him in the gutter. He spent the night in a flophouse, left without paying the next morning, and pawned his revolver for $10. He eventually ended up at his cousin’s home near Germantown, Md., where, on April 20, he was arrested without a struggle.

Booth more than likely didn’t live long enough to learn the fate of Samuel Mudd, who was arrested on April 26.

On May 1, Johnson, who had assumed the presidency following the assassination, ordered the formation of a nine-member military tribunal to try the eight identified and located conspirators: Samuel Arnold, George Atzerodt, David Herold, Samuel Mudd, Michael O’Laughlen, Lewis Powell, Edmund Spangler and Mary Surratt.

The prosecution called more than 350 witnesses before judgments were passed in late June. All the defendants were found guilty. On July 7, Atzerodt, Herold, Powell and Mary Surratt were hanged on the grounds of the Washington Arsenal (now Fort Lesley McNair). Despite abandoning the conspiracy once it encompassed more than kidnapping, Arnold and O’Laughlen were found culpable for their initial collusion and sentenced to life in prison, as was Mudd. Theater stagehand Spangler was sentenced to six years alongside the others at Fort Jefferson, off Key West, Fla. All but O’Laughlin, who died in a yellow fever outbreak, were pardoned by Johnson and released in 1869.

John Surratt fled to Canada and, with the aid of former Confederates and sanctuary from Catholic priests, booked passage to England. Under the assumed name John Watson, he made his way to the Papal States and enlisted in the Pontifical Zouaves. Recognized in late 1866, he attempted to make his way to Egypt under a new identity, but was arrested and extradited to the United States. Thanks to a recent Supreme Court decision, Surratt was tried in a civilian court rather than by a military tribunal; the only charge he faced was murder, the statute of limitations having expired on lesser counts. The jury was deadlocked, but, ultimately, Surratt was released on $25,000 bail. He became a teacher, married and fathered seven children and lived in Baltimore until his death in 1916.

Across the Potomac

“I care not what becomes of me. I have no desire to out-live my country…. I have too great a soul to die like a criminal. O, may He spare me that, and let me die bravely.”

Excerpts from John Wilkes Booth’s diary, written in hiding during April 1865

Not until Thursday evening, April 20 was Thomas Jones, under cover of darkness, and with much stealth and trepidation, able to get the fugitives down to the Potomac and shove them off in his small, flat-bottomed rowboat.

Booth and Herold’s first crossing attempt quickly veered off course due to darkness, the river’s swift currents and strong countervailing tides and their maneuvers to elude federal gunboats. On Friday morning, they came ashore near the mouth of Nanjemoy Creek, still in Maryland, and several miles closer to Washington than when they’d shoved off. Fortunately, Herold had acquaintances in the area who sheltered them until Saturday night, when they successfully crossed over into Virginia.

Early Sunday morning, they came ashore at Gambo Creek, near the site of the modern-day Governor Harry W. Nice Memorial Bridge over U.S. Route 301. Having put the wide Potomac between themselves and the multitude of soldiers, police officers and civilians who were beating the bushes for them back in Maryland, Booth and Herold no doubt felt a wave of relief.

But it was a short-lived reprieve. Within a few days, a federal search party crossed the river and was on their trail. They also soon discovered that the populace in this war-torn section of Virginia was far more wary of offering the kind of assistance they’d received back in southern Maryland. Virginians, unlike their counterparts across the river, had seen firsthand the devastation of war and knew how vindictive the Yankees could be. When Booth and Herold finally found shelter at the Richard Garrett Farm, just south of Port Royal, Va., it was by posing as Confederate soldiers who had surrendered and were on their way home.

The Garrett Farm and the End of the Line

It was at the Garrett Farm, roughly 70 miles southeast of Ford’s Theatre, that Booth, just shy of his 27th birthday, drew his last breath. As he and Herold slept in Garrett’s tobacco barn, a search party of two federal detectives with a detachment 26 volunteers and their commanding lieutenant from the 16th New York Cavalry were closing in. When they reached the Garrett Farm, they silently encircled the barn. Although the lead that had allowed the authorities to pick up Booth’s trail in Virginia had actually been a false sighting, it had nonetheless sent them in the right direction.

After some negotiation, Herold surrendered and was dragged out of the barn, but Booth refused to be taken alive. The barn was set on fire in an effort to drive him out. Then, Sgt. Boston Corbett, one of the cavalrymen, crept up to an open slat in the barn wall and shot Booth from about 12 feet away. The bullet from Corbett’s Colt revolver struck Booth in the side of the neck and paralyzed him from the waist down, although he did not lose consciousness.

Corbett’s public statements about shooting Booth grew more grandiose and preposterous as time went on, but his initial report indicated that he fired because Booth appeared about to shoot his way out. The assassin was then dragged out of the barn and carried up to the porch of the Garrett house, where he lingered before dying around 7:00 a.m., as the sun was rising. Among his final whispered words were, “Tell my mother I died for my country.”

Booth’s body was conveyed by wagon to Belle Plain, Va. There it was placed on the steam tug John S. Ide and transported up the Potomac, under the Navy Yard Bridge to the Washington Navy Yard, where the assassin’s body was transferred to the deck of the ironclad USS Montauk.

As word spread, the scene on the Montauk and on the nearby riverbank took on a circus-like atmosphere as hundreds of curiosity seekers jostled for a glimpse of Booth’s remains. Aboard the ship, an inquest was held, and the corpse, already in an early stage of decomposition, was carefully examined. Friends and acquaintances of Booth’s were summoned to identify the body. Dr. John Frederick May, a surgeon who had removed a cyst from Booth’s neck in 1863, quickly recognized and identified the unusual scar left by the procedure.

The federal government was determined to keep Booth’s remains out of reach of both those who wished to desecrate them and those who wished to sanctify him as a martyr. That night, under cover of darkness, the body was taken by rowboat to nearby Greenleaf’s Point, where it was wrapped in an army blanket, placed in a wooden gun box and secretly buried in the basement of the Washington Arsenal. It remained there until 1869, when the Booth family was finally granted permission to rebury John Wilkes in an unmarked grave in the shadow of his father’s impressive obelisk in Baltimore’s Green Mount Cemetery.