Fredericksburg

Stafford and Spotsylvania, VA | Dec 11 - 15, 1862

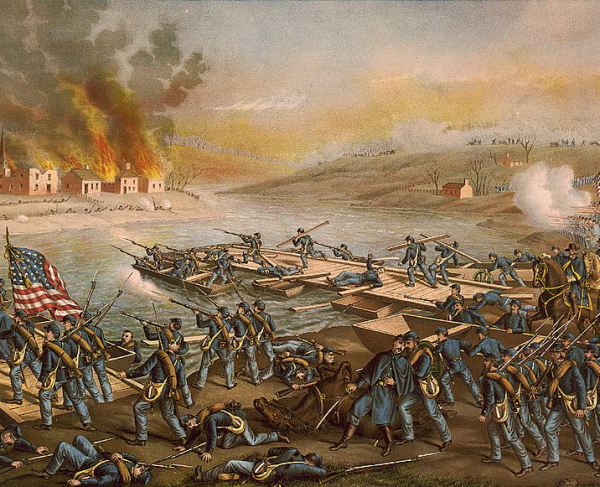

With nearly 200,000 combatants—the greatest number of any Civil War engagement—Fredericksburg was one of the largest and deadliest battles of the Civil War. It featured the first opposed river crossing in American military history as well as the Civil War’s first instance of urban combat.

How it ended

Confederate victory. The Union Army of the Potomac suffered more than 12,500 casualties. Lee’s Confederate army counted approximately 6,000 losses. The Federals retreated, losing an opportunity to advance further into Confederate territory and capture the capital of Richmond.

In context

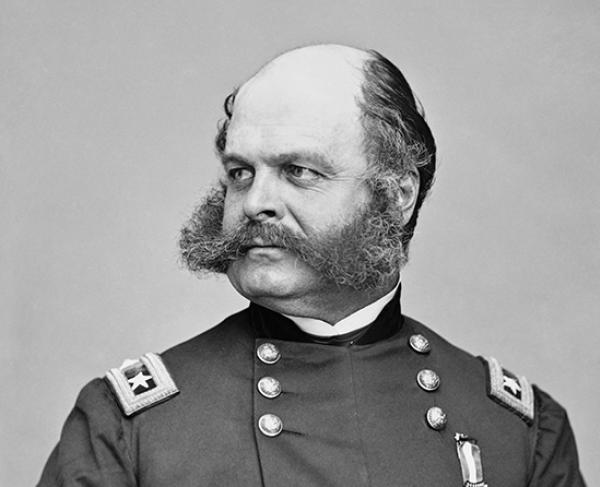

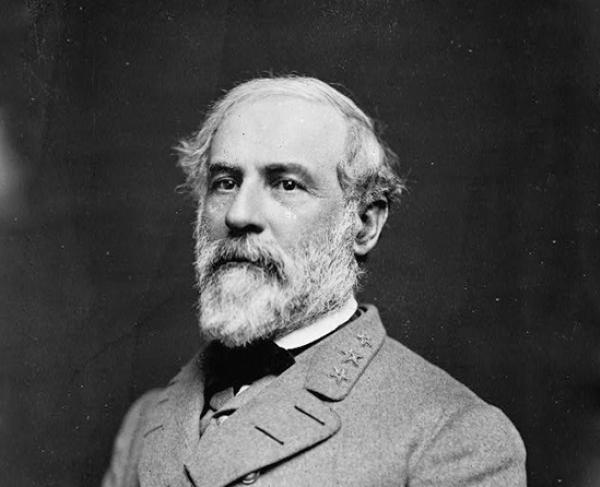

After failing to pursue Gen. Robert E. Lee’s army aggressively after the Battle of Antietam, Maj. Gen. George B. McClellan was removed from command of the Army of the Potomac. His replacement, Maj. Gen. Ambrose E. Burnside, feeling pressure from Washington to move quickly, developed a plan to beat Lee to the Confederate capital city of Richmond.

From his camps around Warrenton, Virginia, Burnside planned to abandon the army’s movement southwest in favor of a quick dash southeast toward the lower Rappahannock River. There, he would cross quickly and position himself between Lee and the direct route to Richmond. The plan had great promise, but, to accomplish it successfully, speed was essential.

Leaving the Warrenton area on November 15, Burnside moves his 100,000-man army 35 miles to Falmouth on the north bank of the Rappahannock in just two days. Opposite Falmouth is the river port town of Fredericksburg, occupied by only a few hundred Confederates. Located halfway between Richmond and Washington D.C., Fredericksburg has largely escaped the ravages of the war. The bridges across the river there have been destroyed earlier, however, so Burnside orders portable pontoon bridges to be sent forward to his army. Arriving in Falmouth, Burnside discovers that bureaucratic and logistical tie-ups in Washington have delayed the bridges and his carefully devised plan to surprise Lee is in jeopardy.

While Burnside waits for his bridges, Lee gathers his army. Gen. James Longstreet’s wing moves east from Culpeper, and Gen. Thomas J. “Stonewall” Jackson’s men hurry toward the Rappahannock from the Shenandoah Valley. Longstreet takes up a position on Marye’s Heights, overlooking Fredericksburg from the west. To the south, Jackson’s men are entrenched in a line stretching over Prospect Hill and onto Hamilton’s Crossing, four miles from the town.

On November 25, Burnside’s long-awaited pontoon bridges begin to arrive.

December 11. An engineer regiment begins to assemble the pontoon bridges opposite the town in the foggy pre-dawn hours. Confederate riflemen, hiding in buildings along the riverbank, harass the engineers and slow their work. Senior Union commanders confer as the bridging process grinds to a halt. Burnside approves a plan to shell the town and drive out the Confederate snipers. Late that morning, over 150 Federal guns arrayed on Stafford Heights bombard the Fredericksburg, blasting scores of buildings and terrifying the civilians, many of whom cower in their cellars. After four hours of shelling, the engineers return to their bridgework and the riflemen resume their shooting.

Another option is desperately needed. Burnside meets with his officers and approves a plan to send a landing party across the river to hunt down the Confederate snipers and secure a bridgehead in the town. Colonel Norman Hall, a brigade commander in the nearby Second Corps, volunteers his brigade to row across the river. Under fire, regiments from Michigan and Massachusetts successfully cross the Rappahannock and drive the riflemen from the riverbank. More Union regiments follow across the river, and the Confederates withdraw after a few hours of house-to-house fighting in the street of town.

December 12. The remainder of Burnside’s army crosses the river and occupies Fredericksburg. His strategy is to use the nearly 60,000 men in Maj. Gen. William B. Franklin’s Left Grand Division to crush Lee’s southern flank held by Jackson, while the rest of his army holds Longstreet in position on Marye’s Heights and supports Franklin if needed.

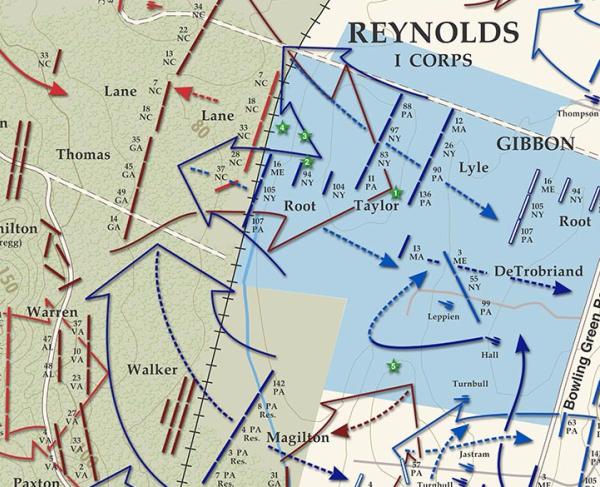

December 13. The Union main assault against Jackson produces initial success. In an area later known as the Slaughter Pen, Maj. Gen. George G. Meade’s division briefly pierces Jackson’s line and threatens the Confederate right. However, lack of coordinated reinforcements and Jackson’s powerful counterattack stymie the effort. Both sides suffer heavy losses with no gain on either side.

Burnside’s “diversion” against Longstreet’s veteran Confederate soldiers produce horrific Union casualties. The front of Longstreet’s position is a sunken farm lane at the foot of Marye’s Heights, full of Confederates three ranks deep. Wave after wave of Federal soldiers advance over open ground to take the road, but each is met with devastating rifle and artillery fire from the nearly impregnable Confederate position. Confederate artillerist Edward Porter Alexander’s claim that “a chicken could not live on that field” proves to be prophetic. Lee, appalled by the carnage, remarks, “It is well that war is so terrible. We should grow too fond of it.”

December 14. That evening, as darkness falls on the battlefield strewn with dead and wounded, it is clear that a Confederate victory is at hand.

December 15. Burnside retreats across the Rappahannock, ending the campaign of 1862 in the Eastern Theater.

12,500

6,000

After the battle, the Federals withdraw across the Rappahannock to avoid being trapped, relinquishing the gains they made. The embarrassing and crushing Union defeat sparks recriminations in Washington, causing a crisis among members of Lincoln’s cabinet, which the president deftly remedies. Six weeks after the battle, Lincoln removes Burnside from command and appoints Maj. Gen. Joseph Hooker commander of the Army of the Potomac.

For the Confederates, the victory at Fredericksburg boosts morale and reinvigorates Lee’s Army of Northern Virginia, which goes on to triumph again at Chancellorsville in May 1863.

The war continues for two-and-a-half more years.

Before she gained fame for her classic novel Little Women, Louisa May Alcott, served as a nurse in Washington, D.C. during the Civil War. Working 12-hour days tending the suffering and dying, Alcott recorded her memories in a semi-autobiographical newspaper series called Hospital Sketches. In addition to conveying the unrelenting pain of those who had fought, Alcott’s work sheds light on the critical human interactions that made her arduous duties bearable—writing letters, reading books, singing songs, sharing jokes, and simply holding the hands of the battle-scarred. Her earliest patients were the defeated troops of Fredericksburg:

Although Alcott’s commitment to nursing remained strong, her service ended after only six weeks. She caught typhoid fever and was sent home. The treatment for her illness—a mercury compound called Calomel—proved to be toxic and caused her to have hallucinations and vertigo for the rest of her life, making her, indirectly, another casualty of the Civil War.

The Battle of Fredericksburg had repercussions for its citizens that lasted well after the engagement between Union and Confederate troops in December 1862. When Gen. Burnside arrived in November of that year, most residents—but not all—chose to flee as 100,000 Union and 80,000 Confederate troops bore down on them. Many took the train to Richmond, while others sheltered on friends’ farms or in makeshift refugee camps set up outside of town, where they braved the December chill.

For the few residents who endured the bombardment of the town in their homes, the horror seemed endless. Ten-year-old Fanny White remembered that “For long hours the only sounds that greeted our ears were the whizzing and moaning of shells and the crash of falling bricks and timber.” Most houses suffered damage, and many were complete ruins. When the cannon fire stopped, the street fighting commenced, bringing violence even closer to civilians. After the Confederates pulled out, the looting began, with Union soldiers pillaging and destroying all property in sight. At Fanny White’s house, there was a mess of “feathers from beds ripped open [ and] every mirror had been run through with a bayonet.” When the fighting ceased, the townspeople still had to confront the horror of dead and wounded soldiers littering their streets.

Confederate troops reviled the Federals for their actions at Fredericksburg, and the anger helped fuel a major fund-raising effort throughout the south. An impressive $170,000 was generously donated to the town to help them rebuild. Still, Fredericksburg was never the same after the Civil War. With ten percent of its city in decimated, the personal wealth of the community plundered, and many of its citizens vowing never to return, it could not reclaim its pre-war serenity. As one reporter commented: “I have seen many towns and villages on the soil of Virginia vying with each other as specimens of the effects of war’s handiwork, but it seems to me that if any spot on earth can fitly represent the abomination of desolation that spot is Fredericksburg.”

Fredericksburg: Featured Resources

All battles of the Fredericksburg Campaign

Related Battles

123,000

78,000

12,500

6,000