Gettysburg

Adams County, PA | Jul 1 - 3, 1863

The Battle of Gettysburg marked the turning point of the Civil War. With more than 50,000 estimated casualties, the three-day engagement was the bloodiest single battle of the conflict.

How it ended

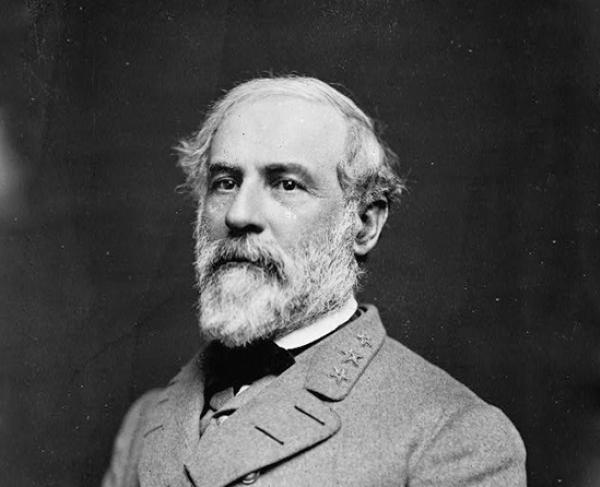

Union victory. Gettysburg ended Confederate general Robert E. Lee’s ambitious second quest to invade the North and bring the Civil War to a swift end. The loss there dashed the hopes of the Confederate States of America to become an independent nation.

In context

After a year of defensive victories in Virginia, Lee’s objective was to win a battle north of the Mason-Dixon line in the hopes of forcing a negotiated end to the fighting. His loss at Gettysburg prevented him from realizing that goal. Instead, the defeated general fled south with a wagon train of wounded soldiers straining toward the Potomac. Union general Meade failed to pursue the retreating army, missing a critical opportunity to trap Lee and force a Confederate surrender. The bitterly divisive war raged on for another two years.

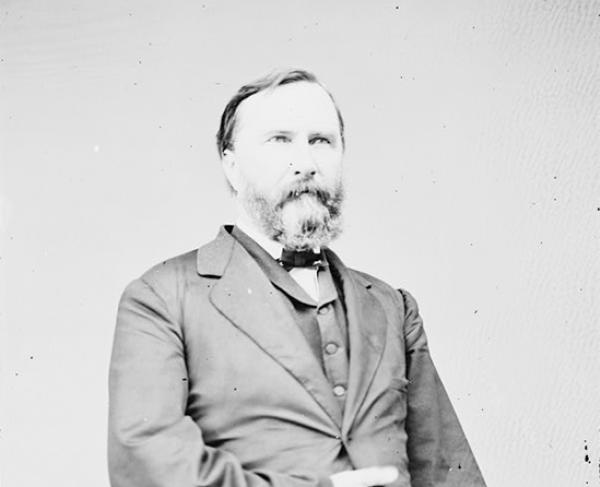

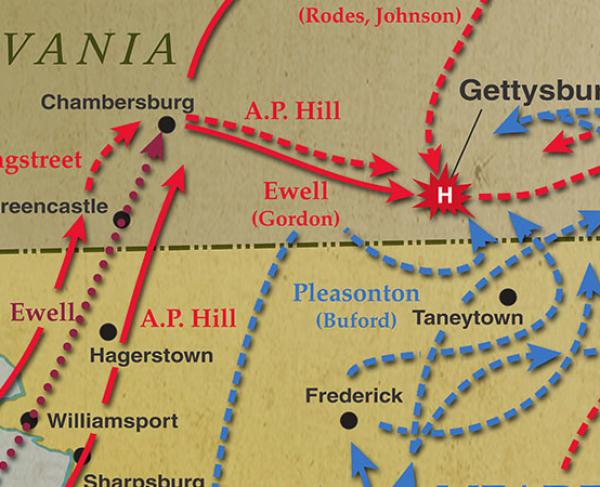

On June 3, soon after his celebrated victory over Maj. Gen. Joseph Hooker at the Battle of Chancellorsville, Gen. Robert E. Lee leads his troops north in his second invasion of enemy territory. The 75,000-man Army of Northern Virginia is in high spirits. In addition to seeking fresh supplies, the depleted soldiers look forward to availing themselves of food from the bountiful fields in Pennsylvania farm country, sustenance the war-ravaged landscape of Virginia can no longer provide.

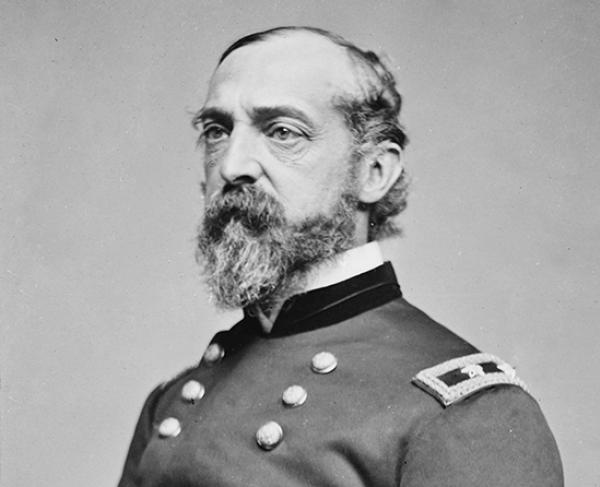

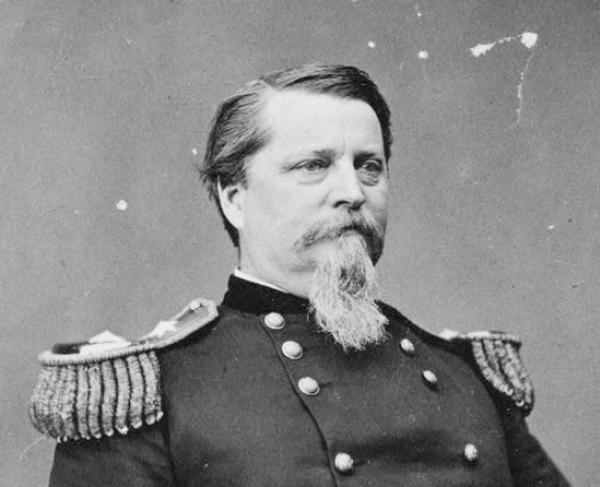

Hooker also heads north, but he is reluctant to engage with Lee directly after the Union’s humiliating defeat at Chancellorsville. This evasiveness is of increasing concern to President Abraham Lincoln. Hooker is ultimately relieved of command in late June. His successor, Maj. Gen. George Gordon Meade, continues to move the 90,000-man Army of the Potomac northward, following orders to keep his army between Lee and Washington, D.C. Meade prepares to defend the routes to the nation’s capital, if necessary, but he also pursues Lee.

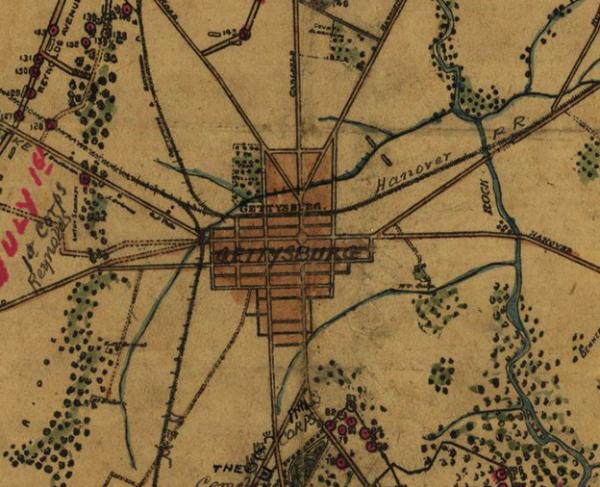

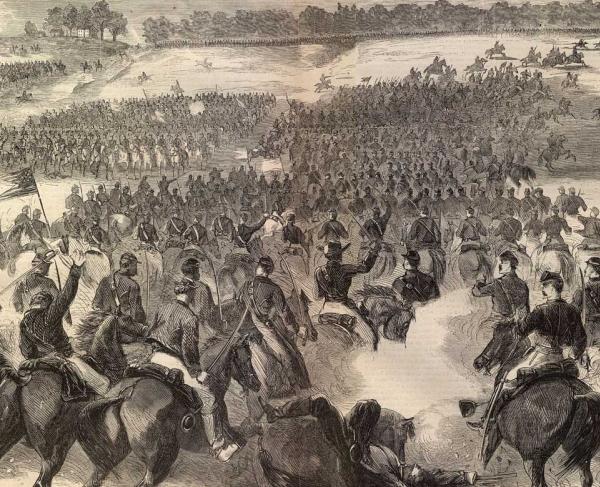

On June 15, three corps of Lee’s army cross the Potomac, and by June 28 they reach the Susquehanna River in Pennsylvania. While Lee loses precious time awaiting intelligence on Union troop positions from his errant cavalry commander, Gen. Jeb Stuart, a spy informs him that Meade is actually very close. Taking advantage of major local roads, which conveniently converge at the county seat, Lee orders his army to Gettysburg.

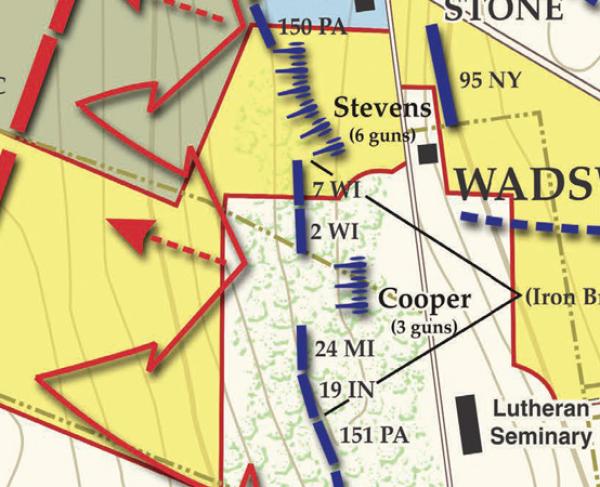

July 1. Early that morning a Confederate division under Maj. Gen. Henry Heth marches toward Gettysburg to seize supplies. In an unplanned engagement, they confront Union cavalry. Brig. Gen. John Buford slows the Confederate advance until the infantry of the Union I and XI Corps under Maj. Gen. John F. Reynolds arrives. Reynolds is killed in action. Soon Confederate reinforcements under generals A.P. Hill and Richard Ewell reach the scene. By late afternoon, the wool-clad troops are battling ferociously in the sweltering heat. Thirty thousand Confederates overwhelm 20,000 Federals, who fall back through Gettysburg and fortify Cemetery Hill south of town.

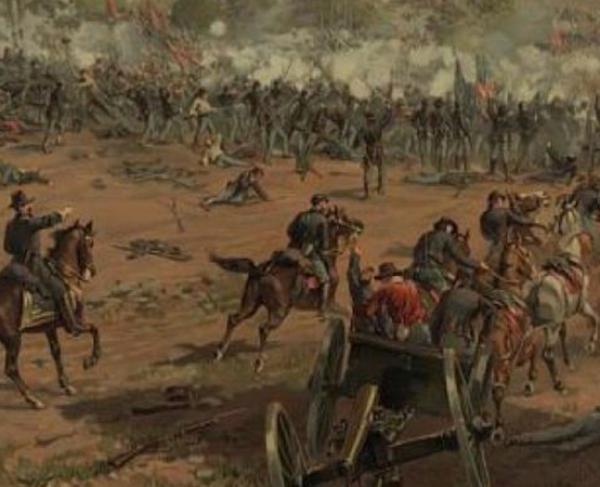

July 2. On the second day of battle, the Union defends a fishhook-shaped range of hills and ridges south of Gettysburg. The Confederates wrap around the Union position in a longer line. That afternoon Lee launches a heavy assault commanded by Lieut. Gen. James Longstreet on the Union left flank. Fierce fighting rages at Devil's Den, Little Round Top, the Wheatfield, the Peach Orchard, and Cemetery Ridge as Longstreet’s men close in on the Union position. Using their shorter interior lines, Union II Corps commander Maj. Gen. Winfield S. Hancock and others move reinforcements quickly to blunt Confederate advances. On the Federal right, Confederate demonstrations escalate into full-scale assaults on East Cemetery Hill and Culp’s Hill. Although the Confederates gain ground on both ends of their line, the Union defenders hold strong positions as darkness falls.

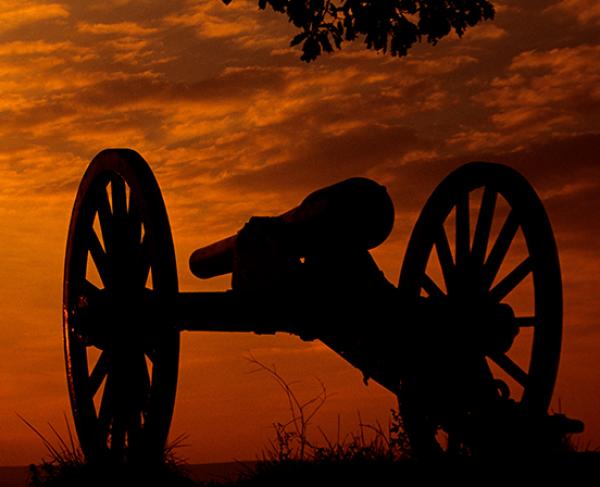

July 3. Believing his enemy to be weakened, Lee seeks to capitalize on the previous day’s gains with renewed attacks on the Union line. Heavy fighting resumes on Culp's Hill as Union troops attempt to recapture ground lost the previous day. Cavalry battles flare to the east and south, but the main event is a dramatic infantry assault by 12,500 Confederates commanded by Longstreet against the center of the Union position on Cemetery Ridge. Though undermanned, the Virginia infantry division of Brig. Gen. George E. Pickett constitutes about half of the attacking force. During Pickett’s Charge, as it is famously known, only one Confederate brigade temporarily reaches the top of the ridge—afterwards referred to as the High Watermark of the Confederacy. This daring strategy ultimately proves a disastrous sacrifice for the Confederates, with casualties approaching 60 percent. Repulsed by close-range Union rifle and artillery fire, the Confederates retreat. When ordered to reform his men after the attack by Lee, Pickett purportedly replied "I have no divsion". Lee withdraws his army from Gettysburg late on the rainy afternoon of July 4 and trudges back to Virginia with severely reduced ranks of wasted and battle-scarred men.

23,049

28,063

As many as 51,000 soldiers from both armies are killed, wounded, captured or missing in the three-day battle. The carnage is overwhelming, but the Union victory buoys Lincoln’s hopes of ending the war. With Lee running South, Lincoln expects that Meade will intercept the Confederate troops and force their surrender. Meade has no such plan. Even as Lee’s escape is hampered by flooding on the Potomac, Meade does not pursue them. When Lincoln learns of this missed opportunity on July 12, he laments, “We had only to stretch forth our hands & they were ours.” Months later, in November 1863, a portion of the Gettysburg battlefield becomes a final resting place for the Union dead. President Lincoln uses the dedication ceremony at the Gettysburg's Soldiers’ National Cemetery to honor the fallen and reassert the purpose of the war in his historic Gettysburg Address:

The world will little note, nor long remember what we say here, but it can never forget what they did here. It is for us the living, rather, to be dedicated here to the unfinished work which they who fought here have thus far so nobly advanced.

Between 6,000 and 10,000 enslaved people supported Lee’s army as cooks, hospital attendants, blacksmiths, and personal servants to officers. Lee surely knew that some would desert him up north in Gettysburg. In January of that year, Lincoln had signed the Emancipation Proclamation, which gave enslaved people in the Confederate states their freedom. Despite this, many slaves remained loyal to their masters on the battlefield at Gettysburg, and later accompanied them home or carried the effects of those who had died back to their families in the South. Others took advantage of the Union victory to break their bonds and join the opposition. Some black camp workers were taken prisoner along with the Confederate soldiers at Gettysburg and, once released, many stayed in the North.

As Confederates advanced on Gettysburg there was terror among the approximately 2,400 residents there as well as in the neighboring towns. White residents feared for their lives and property; African Americans feared enslavement. Many white civilians huddled in basements, but for people of color the stakes were greater, and they fled. In Gettysburg, Abraham Brian, a free black man who owned a small farm near Cemetery Ridge, left with his family, as did Basil Biggs, a veterinarian, and Owen Robinson, an oyster seller. Nearby in Chambersburg, some contrabands—former slaves who sought refuge with the Union Forces—were kidnapped by Confederate cavalry units. The Emancipation Proclamation stated that those seeking freedom from states of rebellion could not be re-enslaved. Accordingly, the Union refused to hand over contrabands to the Confederates, and this, too, prompted retaliation. Confederate soldiers threatened to burn the homes of white residents who were sheltering contrabands. Often, Confederate troops assumed that free blacks were contrabands solely because of their skin color.

After the battle, residents of what had only days before been a peaceful agricultural and college town were in despair. There was literally blood running through the streets, as the dead were piled up in horrific numbers. Slain animals were left to rot. The fields were scorched and barren. Farmers had to rely on the army or government to supply food. Wounded soldiers languished, waiting for medical attention. Camp Letterman, an army field hospital, was established east of Gettysburg and triaged patients until they could be transported to permanent facilities in Philadelphia, Baltimore, and Washington. Nurses for the United States Sanitary Commission, a Union relief organization staffed largely by women, provided essential care and comfort.

Residents of Gettysburg managed to bury the dead in a temporary cemetery. However, prominent members of the community lobbied for a permanent burial ground on the battlefield that would honor the defenders of the Union. The Soldiers’ National Cemetery was dedicated in November 1863 but was not completed until long after. The last of Gettysburg’s wounded shipped out in January 1864, along with the medical personnel. The field tents and temporary shelters came down. The battlefield remains a testament and memorial to the events of July 1–3, 1863.

Gettysburg: Featured Resources

All battles of the Gettysburg Campaign

Related Battles

93,921

71,699

23,049

28,063