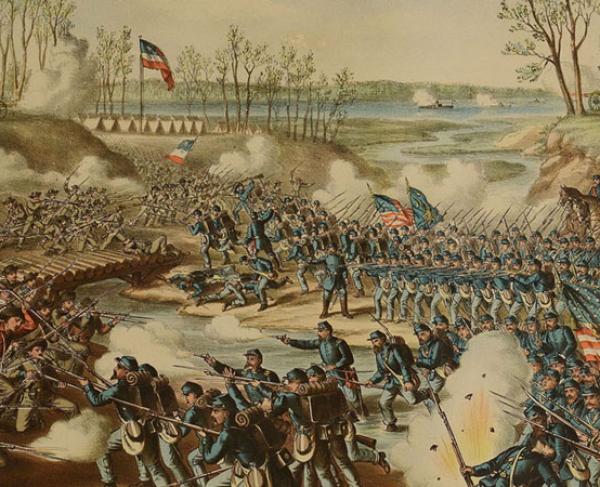

Print depicting the Battle of Shiloh.

Shiloh

Pittsburg Landing

Hardin County, TN | Apr 6 - 7, 1862

The Battle of Shiloh, also known as the Battle of Pittsburg Landing, allowed Union troops to penetrate the Confederate interior. The carnage was unprecedented, with the human toll being the greatest of any war on the American continent up to that date.

How it ended

Union victory. The South’s defeat at Shiloh ended the Confederacy’s hopes of blocking the Union advance into Mississippi and doomed the Confederate military initiative in the West. With the loss of their commander, Gen. Albert Sidney Johnston, in battle, Confederate morale plummeted.

In context

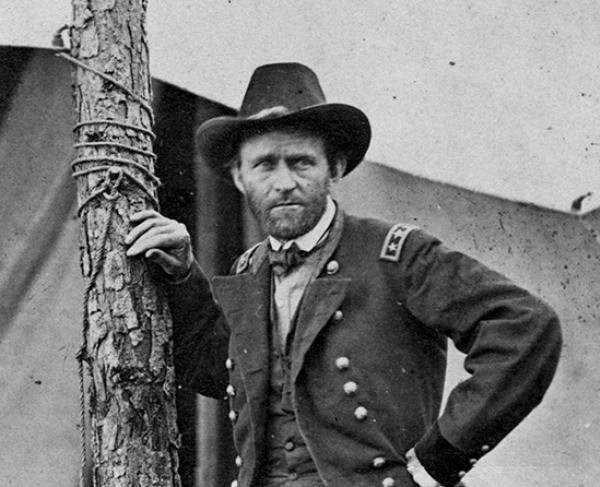

After the Union victories at Fort Henry and Fort Donelson in February 1862, Confederate general Johnston withdrew from Kentucky and left much of the western and middle of Tennessee to the Federals. This permitted Maj. Gen. Ulysses S. Grant to push his troops toward Corinth, Mississippi, the strategic intersection of the Mobile and Ohio Railroad and the Memphis and Charleston Railroad and a vital troop and supply conduit for the South. Alerted to the Union army’s position, Johnston intercepted the Federals 22 miles northeast of Corinth at Pittsburg Landing. The encounter proved devastating—not only for its tactical failure, but for the extreme number of casualties. After Shiloh, both sides realized the magnitude of the conflict, which would be longer and bloodier than they could have imagined.

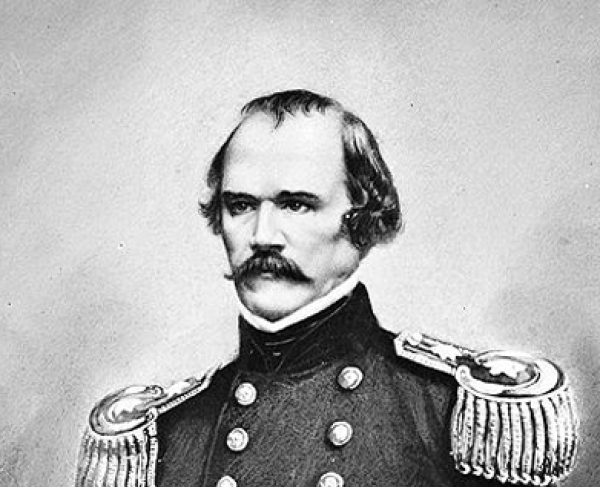

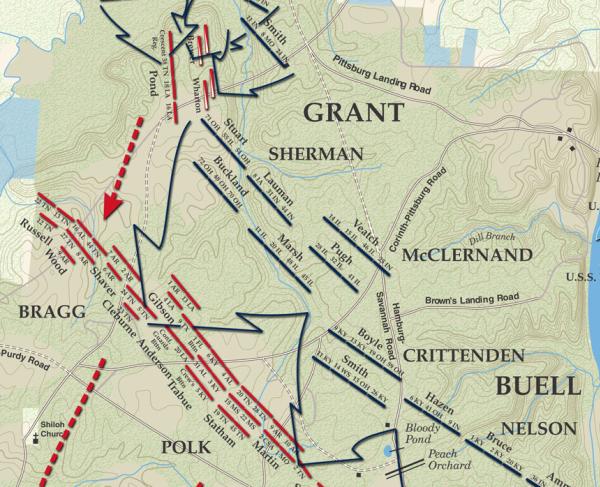

To consolidate his forces and prepare for operations against Grant, Johnston marshals his forces at Corinth. The Confederate retreat is welcomed by Grant, whose Army of the Tennessee needs time to prepare for its own offensive up the Tennessee River. Grant's army camps at Pittsburg Landing, where it spends time drilling recruits and awaiting Maj. Gen. Don Carlos Buell’s Army of Ohio. Grant is ordered not to engage the Confederates until he has been reinforced by Buell's army, which is marching overland from Nashville to meet him. Once combined, the two armies will advance south on Corinth.

Anticipating a Federal move against Corinth, Johnston and his 44,000-man Army of Mississippi plan to smash Grant’s army at Pittsburg Landing before Buell can arrive with more Union troops. On April 3, Johnston places his troops in motion, but heavy rains delay his attack. By nightfall on April 5, his army is deployed for battle only four miles southwest of Pittsburg Landing, and pickets from both sides nervously exchange gunfire in the dense woods that evening.

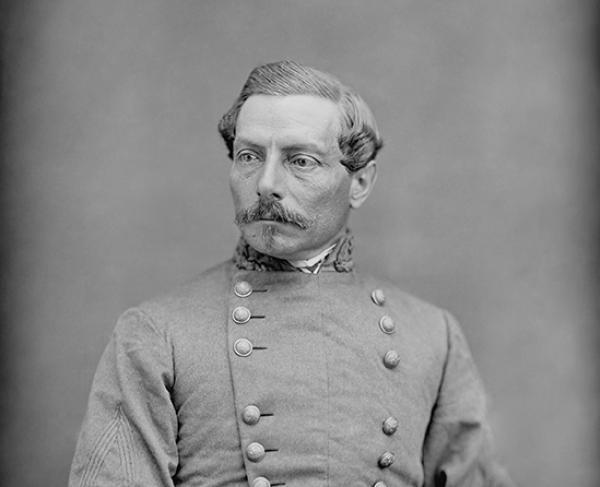

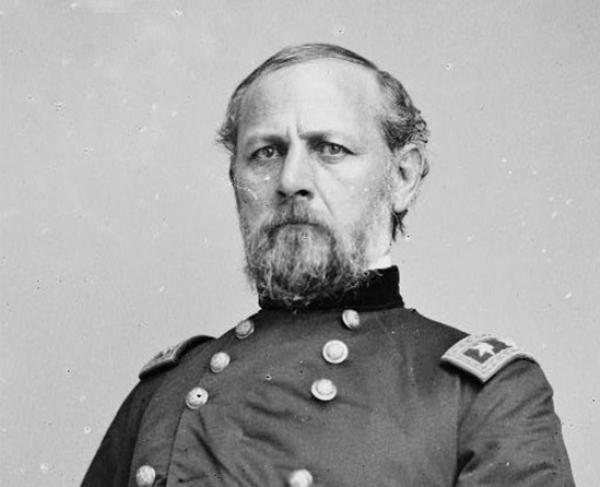

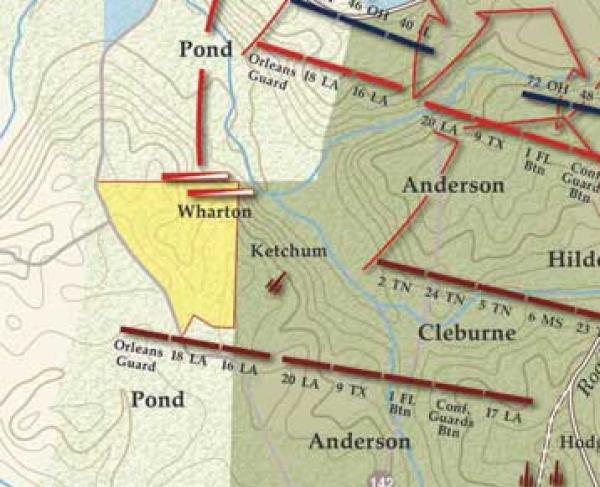

April 6. At daybreak three corps of Confederate infantry storm out of the woods and sweep into the southernmost Federal camps, catching Grant’s men unprepared. Intense fighting centers around Shiloh Church as the Confederates sweep the Union line from that area. Despite heavy fire on their position, Union troops counterattack but slowly lose ground and fall back northeast toward Pittsburg Landing. Throughout the morning, Confederate brigades force Grant’s troops into defensive positions at Shiloh Church, the Peach Orchard, Water Oaks Pond, and a treacherous thicket of oaks posthumously named the Hornets’ Nest by fortunate survivors. That afternoon, while leading an attack on the left end of the Union’s Hornets’ Nest line, Johnston is shot in the right knee. The bullet severs an artery and the commander bleeds to death. Gen. Pierre G. T. Beauregard is appointed the new Confederate commander. Believing his army victorious, Beauregard calls a halt to the attacks as darkness approaches. He is unaware that overnight Buell arrives with reinforcements for Grant. The Union army how has nearly 54,000 men near Pittsburgh Landing and outnumbers Beauregard’s army of around 30,000.

April 7. Grant’s army launches their attack at 6:00 a.m. Beauregard immediately orders a counterattack. The Confederates are ultimately compelled to fall back and regroup all along their line. Beauregard orders a second counterattack, which halts the Federals’ advance but ultimately ends in a stalemate. The timberclads USS Tyler and USS Lexington provides naval artillery support to Grant’s left flank from the Tennessee River. About 3:00 p.m., Beauregard realizes he is outnumbered and, having already suffered tremendous casualties, retreats toward Corinth.

13,047

10,669

On April 8, Grant dispatches Brig. Gen. William T. Sherman and Brig. Gen. Thomas J. Wood to ascertain the Confederates’ position. At Fallen Timbers, six miles south of the battlefield, they encounter Rebel cavalry under Col. Nathan Bedford Forrest. Forrest charges into the Federals ahead of his own troops and is shot by Federal infantry at point-blank range. Although he will later require difficult surgery to remove the life-threatening bullet, Forrest’s reckless aggression pays off. Federal forces flee in the direction of Pittsburg Landing, allowing the Confederates to escape.

The loss of life on both sides at Shiloh—which, ironically, means place of peace in Hebrew—was staggering. But there were other sad consequences of the battle as well. Johnston’s death was a damaging blow to Confederate morale, particularly for President Jefferson Davis, who held Johnston high in personal and professional esteem. After the war, Davis wrote, “When Sidney Johnston fell, it was the turning point of our fate; for we had no other hand to take up his work in the West.”

Grant, though victorious, was vilified in the press after being caught unprepared at Pittsburg Landing on April 6. Critics called for him to be dismissed, but Abraham Lincoln defended his general , declaring “I can’t spare this man, he fights.” Corinth fell to the Union by the end of May, allowing Grant to focus on gaining control of the Mississippi River.

Grant’s previous victories at Forts Henry and Donelson had boosted his confidence. He believed he had the superior army and that the Confederacy would soon collapse. Sherman, in charge of day-to-day operations at Pittsburg Landing, shared his commander’s arrogance, “I always acted on the supposition that we were an invading army. . . we did not fortify our army against an attack, because we had no orders to do so, and because such a course would have made our men timid.” Despite intelligence about and evidence of Southern forces in the area, Sherman was dismissive. To the Major who reported encountering Confederate troops nearby on April 4, he replied, “You militia officers get scared too easy.” So, when taken unawares by Rebel forces on April 6, the Union troops had no defensive plan in place. With the fighting concentrated in a small area—the Snake River on one side and the Tennessee River on the other—this narrow funnel-shaped zone became a cauldron of death. The battle became a free-for-all, with soldiers attacking one another and calvary working to prevent men from fleeing, rather than launching attacks.

For Grant, who was nine miles downriver at his headquarters, his folly may had been to rely on Sherman, who had several warnings about a Confederate attack but failed to heed them. On April 5, Sherman wrote to Grant, “I have no doubt that nothing will occur today other than some picket firing. The enemy is saucy, but. . . will not press our pickets far. I do not apprehend anything like an attack on our position.” His words soon came back to haunt him. Sherman’s men had just finished breakfast on April 6 when they got word of Confederate units on the march. Sherman rode out to investigate. As he raised his spyglass to view the oncoming troops, the orderly next to him was shot dead by enemy fire. Sherman was shot in the hand. It was only then that reality sunk in. “My God,” he said, we are attacked!”

As news of the carnage at Shiloh spread to North and South alike, the public’s notion that the war would be short-lived ended. Newspaper accounts, many erroneous but all shocking, described the chaos and bloodshed on the battlefield. This changed people’s romantic view of the conflict. The war had turned ruthless. In his memoirs, Grant wrote, “Up to the battle of Shiloh, I, as well as thousands of other citizens, believed that the rebellion against the Government would collapse suddenly and soon, if a decisive victory could be gained over its armies….” After Shiloh, he admitted, “I gave up all idea of saving the Union except by complete conquest.” Sherman reinforced this view, “…we cannot change the hearts and minds of the people of the South, but we can make war so terrible…that the rebels will tire of it.”

The most radical change in view occurred among the soldiers who fought at Shiloh. After the battle Confederate private Sam Watkins of the First Tennessee wrote: “I had been feeling mean all morning, as if I had stolen a sheep … I had heard and read of battlefields, seen pictures of battlefields, of horses and men, of cannons and wagons, all jumbled together, while the ground was strewn with dead and dying and wounded, but I must confess I never realized the ‘pomp and circumstance’ of the thing called ‘glorious war’ until I saw this.”

Shiloh: Featured Resources

All battles of the Federal Penetration up the Cumberland and Tennessee Rivers Campaign

Related Battles

65,085

44,968

13,047

10,669